God's vision of creation is a true garden of delights for his people. This thoughtful series helps us redeemed sinners to live in the presence of our risen, ruling, and returning Savior who is bringing about the restoration of all things.

Overview of the Series

Introduction

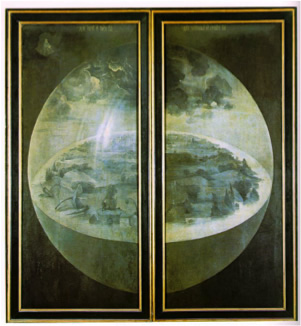

In the early 16th century, Hieronymus Bosch painted a triptych that is both powerful and perplexing. Using oil paint and oak, Bosch imagined what is known as The Garden of Earthly Delights.

When the wings of this triptych are closed, the viewer sees God creating the world. The scene is painted in grisaille, a technique that renders a scene entirely in one color. This lack of contrasting colors gives the creation story an eerie otherness. God, the Father, sits in the upper right hand corner with a bible (the creative Word) in his lap. From that word comes a world. The world is huge and yet delicate, a semi-transparent sphere suspended in darkness. It is separate from God and yet governed by him as one watches creation unfold. It is the third day.

Upon opening this triptych, however, the viewer is overwhelmed with vibrant color and artistic imagination. With this power comes perplexity. The interior scenes are disturbing. Reading the panels from left to right, one begins with the creation of Adam and Eve. Here, God is present and active in his wonderful creation. The central panel depicts a world without God. The scene is filled with realistic and imagined figures engrossed in sexual and physical delights. The final panel depicts a world condemned. It is a hellish landscape, with the remnants of civilization in a city at the top and then a movement from imagined to very real tortures and death at the bottom.

This imaginative journey is as powerful as it is perplexing. Bosch takes his viewers from a rather plain and placid depiction of creation to a powerful explosion of action and wonder, both beautiful and perverse. Consider the contrast: the story of creation is eerie and other and intentionally plain; open its doors, however, and one finds in the center a world filled with delight. That world is without God and, for many viewers, without any clear meaning, but it remains framed by the memory of creation (left panel) and the anticipation of judgment (right panel).

In some ways, Bosch's painting captures our 21st century experience of ecological awareness. For most Christians, the story of creation is simple and plain. It may come as a childhood memory or as a passing encounter with Genesis in an adult instruction class, but it is not explored in any great detail. It pictures God and the world but it lacks the depth and complexity of scientific discovery and secular imagination. When Christians pass through that story into the world, they find themselves overwhelmed with an explosion of debate in ecological conversations. Sometimes the visions are beautiful and other times they are perverse. Sadly, the unformed Christian imagination only faintly remembers the past (God's creation of the world) and fearfully anticipates the future (where God delivers our souls from hellfire and damnation into a heavenly realm). Such an unformed and uninformed Christian vision makes it very difficult to find meaning in the present world. When one speaks about Christians and creation, one immediately thinks of arguments against evolution rather than the fullness and the wonder of the biblical witness or the fullness and wonder of the Christian life.

Historically, the triptych was a form often associated with religious devotion. Although Bosch paints in this form, art historians doubt whether this painting ever graced the altar of a church. Its imagery is too perplexing and disturbing. One wonders, however, if the church were to produce a triptych relating to creation, what would it look like? What kind of art would lead God's people into the depth and the wonder of his creation, care, and recreation of the world?

The Sermon Series

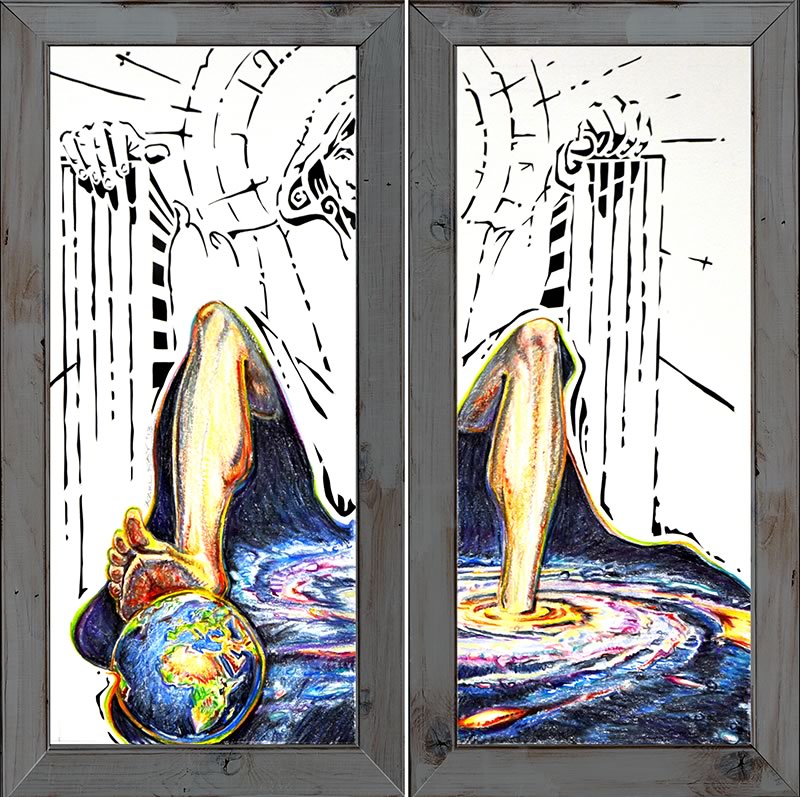

In constructing this sermon series, I commissioned an artist to answer that question. Lutheran pastor, Karl Fay, is the artist and his triptych provides the visual imagery for this series. You can read Fay's description of his work and we will reference it throughout the series. The images are also available for you to use for bulletin covers or visual display. Right now, I would like to highlight the scale of his work. Fay's work is not designed to grace the altar of a church. It is smaller than that. Although he uses the triptych form, he scales his work for art that would be found within a home. Consider what that means. Fay's work suggests that our worship of God extends out of the congregation and into the world, in our care for the created world God has given us as our home.

The sermons series, itself, is a triptych: a triptych that opens the pages of Scripture and explores the wonder of creation.

Enfolded Exterior

The opening panel is of the risen Christ, ascended into heaven and ruling at his Father's right hand. What you see in this image is that Jesus is the Second Adam. God has placed all things under his feet. He was there at the first creation and he now rules over creation itself until he returns and brings about the restoration of all things. As we engage in care for creation, we are living in the rule of Christ, the Second Adam, awaiting the restoration of all creation and the full fruition of eternal life in him. This is the image that opens this sermon series: Christ, the Second Adam, who rules over all creation.

Enfolded Interior Panel 1

The rest of the sermons in this series will open that image and explore what it means for Christians to believe that Christ rules over all things. In Bosch's triptych when the story of creation is opened, it leads the viewer into an explosion of color and life. In this sermon series, as God's people explore what it means to confess that Jesus rules over creation, they experience an explosion of color and life as they encounter this world. The first panel explores the experience of delight in creation. God has surrounded us with a created world that continuously sings his praise. The biblical witness opens our eyes to see God's delight in creation and creation's delight in God. In this sermon, God's people will learn to join creation's praise.

Enfolded Interior Panel 2

The middle panel explores what it means to be part of the community of creation. Human culture has often been set in opposition to the natural world. In Revelation, however, as God gives John a vision of the throne in heaven, John sees that both creation (Rev. 5:11-14) and culture (Rev. 7:9-12) gather before the throne of God to sing. In anticipation of that day, God has made a covenant with both his human creatures and all living creatures (Gen. 9:1-17). This sermon will examine that covenant and the complexity of life that it describes. We are to live in community with all creation, caring for all living creatures and yet receiving from God's hand living creatures for our sustenance. This good design of God creates a life of caring consumption that will be the subject of the sermon.

Enfolded Interior Panel 3

The last panel explores what it means for Christians to listen to God's word and live in hope of Christ's return. Ecological engagement can be exhausting and, at times, dispiriting. If your congregation has engaged in ecological initiatives during this sermon series, this sermon encourages God's people to continue in such work. It asks that they approach these things not as temporary programs, quick fixes to lasting problems, but as a way of life in the kingdom where we anxiously await Christ's return, looking forward to his recreation and restoration of all things. Whereas Bosch's triptych suggests a world framed by a faint memory of creation and fearful anticipation of final judgment, this final sermon will guide Christians in ecological conversations that are framed by a firm sense of the past (God's original creation and our fall into sin) and a faithful vision of the future (Christ's return and restoration of his people as he recreates all things). Knowing the past, God's people repent for sin that has destroyed creation; knowing the future, God's people live in hope of God's final recreation and restoration. Thus, we enter the world and ecological conversations in repentant hope. We are honest and forthright about the sinful abuse of God's creation and yet we are also confident and filled with hope as our faithful action embodies the first fruits that forecast that final day.

The rest of the sermons in this series will open that image and explore what it means for Christians to believe that Christ rules over all things. In Bosch's triptych when the story of creation is opened, it leads the viewer into an explosion of color and life. In this sermon series, as God's people explore what it means to confess that Jesus rules over creation, they experience an explosion of color and life as they encounter this world. The first panel explores the experience of delight in creation. God has surrounded us with a created world that continuously sings his praise. The biblical witness opens our eyes to see God's delight in creation and creation's delight in God. In this sermon, God's people will learn to join creation's praise.

The middle panel explores what it means to be part of the community of creation. Human culture has often been set in opposition to the natural world. In Revelation, however, as God gives John a vision of the throne in heaven, John sees that both creation (Rev. 5:11-14) and culture (Rev. 7:9-12) gather before the throne of God to sing. In anticipation of that day, God has made a covenant with both his human creatures and all living creatures (Gen. 9:1-17). This sermon will examine that covenant and the complexity of life that it describes. We are to live in community with all creation, caring for all living creatures and yet receiving from God's hand living creatures for our sustenance. This good design of God creates a life of caring consumption that will be the subject of the sermon.

The last panel explores what it means for Christians to listen to God's word and live in hope of Christ's return. Ecological engagement can be exhausting and, at times, dispiriting. If your congregation has engaged in ecological initiatives during this sermon series, this sermon encourages God's people to continue in such work. It asks that they approach these things not as temporary programs, quick fixes to lasting problems, but as a way of life in the kingdom where we anxiously await Christ's return, looking forward to his recreation and restoration of all things. Whereas Bosch's triptych suggests a world framed by a faint memory of creation and fearful anticipation of final judgment, this final sermon will guide Christians in ecological conversations that are framed by a firm sense of the past (God's original creation and our fall into sin) and a faithful vision of the future (Christ's return and restoration of his people as he recreates all things). Knowing the past, God's people repent for sin that has destroyed creation; knowing the future, God's people live in hope of God's final recreation and restoration. Thus, we enter the world and ecological conversations in repentant hope. We are honest and forthright about the sinful abuse of God's creation and yet we are also confident and filled with hope as our faithful action embodies the first fruits that forecast that final day.

Concluding Thoughts

Thank you for considering use of this sermon series. Now is truly the time. Our culture has experienced a renaissance in ecological awareness. From your neighbor who weekly sets a recycling bin at the curb to your community that gathers every year for Earth Day in a public park, people are engaged in ecological conversation and action. Unfortunately, the church seems to have lost its voice. Like Bosch's monochromatic vision of creation, the church's story seems devoid of life. Ever since Lynn White's famous address to the American Academy for the Advancement of Science in 1966,1 the church has been seen as the cause of much ecological destruction. Some see the church devaluing creation, as Christians proclaim that humans are meant to dominate the world and master its resources for their use. Others see the church treating creation with careless disregard, as Christians tell how God has saved their souls (not their bodies) and will ultimately take them from this world to live with him in heaven. Unfortunately, such readings are not faithful to the biblical witness.

When the pages of Scripture are opened and the biblical witness is explored, God offer his people a vibrant and beautiful confession of faith and way of life in his world. Unfortunately, often our conversation never leaves the first chapter of Genesis and the voice of the church is only heard in the context of a creation/evolution debate. This sermon series seeks to explore other aspects of the biblical witness to creation. If you are looking for a sermon on the creation/evolution debate, you will not find it here. This is not because that debate is not important or that Christian faith does not have a witness but rather because the Christian witness is so much more than the limits of that debate. Instead, this series will explore the fuller vision of Scripture as it speaks of creation. Such a witness will correct the errors of our world, its misconceptions of our Christian witness, encourage action, and build bridges within our culture's ecological climate.

While these are all good things, however, ultimately, the real purpose of this series is to confess God's vision of creation. God has given it to us to hear, to read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest as we grow in the faith. God's vision of creation is a true garden of delights for his people. It helps us redeemed sinners live in the presence of our risen, ruling, and returning Savior who is bringing about the restoration of all things. May God bless your endeavor to share that word with his people.

For each sermon in the series, you will find a brief sermon study and then a full sermon.

Sermon Study:

The sermon study will consider the topic of the sermon within the contexts of biblical theology and ecology and provide suggested readings, hymns, and a collect for the service.

- Biblical Theology and Ecology: this section will reflect upon biblical theology in the context of current ecological discussions.

Ecological discourse is vibrant and diverse, ranging from well-funded scientific studies of habitats to unfunded blogs on the personal implementation of green practices. It is impossible to cover all that is being discussed. It is possible, however, to highlight some of the themes that surface within these discussions and then to draw upon the biblical witness that addresses those themes. This section will explore the fundamental biblical orientation toward creation that shapes the church's faithful response in ecological conversation. - Sermon Formation: this section will provide a sense of the content and flow of the sermon. Since it is difficult to preach another person's sermon, this section will identify the focus of the sermon (the main idea) and the function (how this main idea, by grace, will shape the lives of God's faithful people). In addition, you will also find here the proclamation of law (malady) and gospel (means) that lies at the heart of the sermon. By providing a sense of the main content and flow of the sermon, it should be easier to edit and creatively adapt the sermon to suit your needs.

Full Sermon:

You will also receive a full sermon. These sermons represent how one could preach on this topic. They seek to proclaim God's word, his vision of creation, and form God's people, enriching their lives as they delight in creation, discover community, and live in repentant hope. Yet, preaching another person's sermon is like trying to wear another person's clothes. They never quite fit. For that reason, you may adopt the overall flow of the sermon but switch out the stories or you may choose one moment in the sermon and build a sermon of your own around that. Why provide full sermons? Because reading another person's sermon gives you the opportunity to be spiritually fed and strengthened as you prepare to preach. With the theme, the structure, and the full sermon in hand, my prayer is that you will be equipped to invite God's people to listen to God's word in this creation series and that God will speak through your words to prepare his people for active and contemplative engagement in the wonder of his world.

Bulletin/Newsletter Description:

Is this world just something we pass through? Is Jesus only concerned about your soul? Or does God have a much fuller vision of life for you? Christ and Creation explores the wonder of God's creation, teaching us how to live in community with creation, faithfully and responsibly tending to the world God has made and entrusted to our care.

Author Bio

The Rev. Dr. David Schmitt holds the Gregg H. Benidt Memorial Endowed Chair in Homiletics and Literature at Concordia Seminary. The responsibilities of this position involve teaching courses in homiletics and literature and serving as a resource to the church-at-large, through writing, speaking, and conducting workshops and symposia.

Dr. Schmitt joined the faculty in 1995 and has taught courses in preaching, evangelism, pastoral ministry, Christianity and literature, and the devotional life. He serves as Professor of Practical Theology.

Before coming to the seminary, he served as pastor of St. John the Divine in Chicago IL. He earned his M. Div. from Concordia Seminary, St. Louis (1988), an MA in English from the University of Illinois (1990), and an MA and a PhD in English from Washington University in St. Louis (2005).

- Lynn White, Jr. "The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis" in Science 155 (1967): 1203-1207.

Artist's Description of Art Work

Title: ENFOLDED, colored pencil and cut paper triptych, " x ", 2013

Artist Statement

Triptych (Greek adjective meaning "three-fold") is a form of art that is tied to Christian church history and architecture from the early Christian era onward. Triptychs were prominent panels atop altars in grand, glorious medieval cathedrals. One cannot see all of the imagery in a triptych in one glance. Rather, like a book, one opens it and looks inside. One enters into a world.

The scale of this triptych doesn't place it in a vaulted cathedral, but in a home. In the midst everyday life. Alongside carpooling and cooking, playing and exploring, mowing and gardening.

How does one's confession of Jesus as risen and reigning Lord of creation, the one who brings new creation, play out in this arena, the arena of one's everyday life?

Artist Bio

Karl Fay was born in Topeka, KS in 1982. He enjoys working primarily with drawing and mixed media, focusing on colored pencil and cut and torn paper. He completed his B.A. in Studio Art at Concordia University in Seward, NE and his MDiv. at Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, MO.

He lives with his wife, Kendra, and three children in Palatine, IL, actively creating art, teaching and raising up other artists, while serving as Discipleship Pastor at Prince of Peace Lutheran Church in Palatine.

Karl has a blog with commentary on images and recent work.

Part One

Sermon Study

Biblical Theology and Ecology:

How does the church enter into ecological conversation? How does one begin a sermon series on creation? In both cases, the answer is the same. By recognizing that such a conversation is not new for the church. In fact, the biblical witness is filled with God's people engaged in holy conversation about the care of creation. Such a conversation might be new for our generation, but it is not new for the church.

The very fact that it sounds new for our generation signals our loss of the larger biblical witness. Think of the conversations you have had in church during your lifetime. The discussions in bible class. The sermons on Sunday. The devotional literature God's people use during the week. What topics appear again and again in such conversations? What talk is normalized as appropriate "church talk" through these frequent conversations? Now, turn to the Scriptures. Read through the psalms and the prophets. Listen to God's people in worship, in prophecy, in prayer. Overhear how frequently the language of creation appears in their witness. Our contemporary theological conversations may have made it seem strange to talk about creation but a close reading of Scripture will help us change our speech. We will overhear how God's people speak about creation and do so out of faithful understanding of the rule of God.

This first sermon in the sermon series seeks to recover the language of creation by anchoring it in the rule of Christ over all things. We are accustomed to hearing of Christ as Lord of our lives. We confess our sins and receive forgiveness and know Jesus as the one who takes away our sins. We are also accustomed to hearing of Christ as the Lord of the church. We gather on Sunday to receive absolution, hear the proclamation of the word, receive the sacrament, and delight in the presence of Christ, coming with his gifts. What this sermon seeks to do is recover our confession of Christ as Lord of all. In addition to being Lord of our lives and Lord of the Church, Jesus Christ is the Second Adam who rules over all things. When one confesses that Jesus Christ is Lord of all, conversations of creation become natural in his church. It is the way God's people rejoice in the rule of Christ, confessing that God has given him to the church as the one who rules over all things.

The sermon thus begins in prayer. In deep meditation upon the texts of Scripture and the revelation in those texts that Christ rules over all things. By understanding what it means for Christ to be the Second Adam, we gain an understanding of who we are as God's creatures in the world he created, redeemed, and now rules.

Psalm 8 anchors the sermon in a vision of God's design for the first Adam life in creation. Psalm 8 offers a paradoxical vision of the human creature in relation to God and God's creation. On the one hand, the human creature is astonishingly small. As the psalmist looks upon creation, he observes the heavens, the stars and the moon, the works of God's fingers. Those lights that we can barely see, God has created, touched with his fingers, and put into place. When gazing at the vastness of the heavens, the psalmist sees the smallness of human beings. "What is man that you are mindful of him?" he asks. On the other hand, the human creature is given great authority. The psalmist recalls creation and the fact that God gave the human creature "dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under his feet," and the psalmist goes on to name not only the beasts of the field but the birds of the air and the fish of the sea. Thus, the human creature is paradoxically both small and great at the same time. This paradox is by divine design and invites us to live in the tension of a humble authority, a servant's lordship, as we exercise our humble dominion in God's gift of a wonderous world.1

As with most paradoxes, it is easy to lose sight of this tension, to overemphasize one truth at the expense of the other and thereby fracture and deny God's design. For example, when some see the expanse of the universe, the clusters of galaxies, they argue that humanity is merely an accident. For them, any claim to human significance is hubris, and reveals how vastly deluded human beings are. Here, overemphasizing our smallness leads some to lose sight of the greatness given by God. For these individuals, humans have no God-given role of dominion in creation and claims to such a role amount to a form of prejudice known as speciesism, elevating the human species over others.2 On the other hand, others can overemphasize the greatness and lose sight of humility. In 1966, medieval historian Lynn White Jr. suggested that the historical roots of the current ecological crisis lay in Christian claims for the dominion of human beings over creation.3 White's analysis, oft repeated, has fostered an ecological distrust of the Christian worldview. Christianity is seen as asserting dominion of the human creature over all things without an awareness of humanity's limitations. Here, by overemphasizing greatness, the church has lost sight of the smallness of the human creature.

The Christian worldview, however, seeks to articulate the paradoxical vision offered in Psalm 8. The human creature is both small and great at the same time. As we live in this world, we are given a humble glory. We are called to exercise a servant's authority. The human creature is both humble and exalted in relation to God's wonderful creation. Dominion, therefore, involves service of a paradoxical kind.

How does one articulate this paradox, this servant's authority, in God's world? One way is by anchoring our vocation in Christ. We do not exercise authority over creation apart from Christ. Rather, we exercise authority over creation in him and through him.

In his letter to the Ephesians, the apostle Paul offers a vision of Christ that shapes the life of the church in the world. As Paul speaks of the power of God made known in Jesus, Paul proclaims that Jesus himself is the fulfillment of Psalm 8. Though humanity made a mess out of its rule over creation, Christ has come into creation, taken on human form, and borne the suffering and the punishment for the sin of our failed exercise of human authority. Christ has come to know creation intimately. He has taken on human flesh and lived within this world. Christ has suffered the full effects of human sin for us. God, the Father, then raised Jesus up from the dead and seated him in the heavenly realms.

As Paul speaks of this exaltation of Christ in Ephesians 1:22, notice how he quotes from Psalm 8. Paul proclaims that God "put all things under his feet and gave him as head over all things to the church." With the words "put all things under his feet," Paul reads Psalm 8:6 ("you have put all things under his feet") as fulfilled in Christ. Christ is the fulfillment of God's original design for Adam. Christ embodies the proper human rule over creation. When Christ rose from the dead, he did not discard his human nature. Rather he glorified it. He brought his humanity into heaven and he now sits at the right hand of God and rules over all things. This rule of Christ is nothing other than the exercise of God-given dominion through a servant king. In Christ, one finds that beautiful paradox of humble dominion, exalted service, a rule over creation that understands creation's purpose, God's love, and the human place.

Even more importantly, Paul states that God has given this Christ "as head over all things" to the churches. Consider what that means. Jesus is more than our Savior. He is also the ruler of all creation and has been given as such to the church. Whereas some Christians can enter into ecological discussions with a wrong understanding of human dominion, others can enter into such discussions without any place for human dominion at all. This passage allows the church to enter into such discussions confessing the rule of Christ and how that rule shapes Christian witness in word and in deed.

Paul's vision of Christ as God's gift to the church offers one way of framing our discussion. Christ has been given to us as the one who rules over creation as God intended such rule. As followers of Christ, therefore, we are brought into a loving rule in creation. We have a humble authority, a servant's glory, that cares for creation as part of the rule of our Lord. We are not lording it over creation, misusing it for our own purposes, and we are not distant from creation, awaiting our release from a material existence. Instead, we enter into creation and begin to serve in the mystery of mastery that has been given to us and taught to us by Christ.

Sermon Formation:

| Focus | Christ is the Second Adam who rules over creation in love. |

| Function | that the hearers care for creation as an expression of Christ's rule through them. |

| Malady | We have misunderstood our place in God's design, using the dominion God has given us as an exercise of power rather than an expression of care for creation that it might flourish. |

| Means | Christ entered into creation and bore in his body the wrath of God for our sinful misuse of dominion. In his resurrection, he is the Second Adam, who now rules over all things as God desires and includes us in that gracious rule. |

| Structure |

the sermon is structured on the basis of contrast.4 It opens with the idea of meditating on a verse from a psalm and discovering the wonder of God's word breaking forth in our lives. The sermon then contrasts two different ways of meditating on a verse from Psalm 8: an inappropriate reading of "you placed all things under his feet" (where we use this verse to claim power over creation in an act of authoritarian rule) and Paul's reading of Psalm 8 (where we see Christ as the Second Adam who rules over creation with compassionate care). At the heart of the sermon is the image of Christ as the Second Adam, based on Paul's prayer in Ephesians 1:22 and depicted in the opening image of the triptych for this sermon series. |

- For a theological elaboration on our humble dominion, see Charles Arand's work in Together with All Creatures: Caring for God's Living Earth. A Report of the Commission of Theology and Church Relations. The Lutheran Church "“ Missouri Synod (St. Louis: CPH, 2010), 39-54.

- See Richard D. Ryder, Animal Revolution: Changing Attitudes toward Speciesism (New York: Berg, 2000).

- See Lynn White, Jr. "The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis" in Science 155 (1967): 1203-1207.

- For a description of this structure, see the information posted on this sermon structure located at The Pulpit on concordiatheology.org. See http://concordiatheology.org/sermon-structs/thematic/comparisoncontrast/.

I: Seeing Your Savior Anew

Sometimes, a verse from a psalm becomes more than a verse from a psalm. It breaks open. It buds and blossoms and brings forth fruit.

In the twelfth century, in England, at St. Albans, a psalter was being put together. Two minor artists were tasked with minor work. They were not invited to illuminate the 40 full-page illustrations of the life of Christ that precedes the psalter. They were not invited to illuminate the full-page illustrations of David the musician or the martyrdom of St. Alban that conclude the psalter. No, they were given the task drawing the first initial of each psalm. In comparison to the scope of this project, this was a minor endeavor... Seeing Your Savior Anew

Addenda

| First Reading | Psalm 8 |

| Second Reading | Ephesians 1:15-23 |

| Hymnody |

LSB 538 "Praise Be to Christ" |

| Collect | Almighty God, you raised your Son Jesus Christ from the dead, seated him on high, and gave him to the Church as the Second Adam who rules over your creation, Form us in following him, that we might care for creation, not in an exercise of power but in humble service and self-sacrificial love, Through Jesus Christ, your Son, our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen. |

Part Two

Sermon Study

Biblical Theology and Ecology:

"In Sheol, who will give you praise?" (Psalm 6:5). The question is haunting. In Psalm 6, David is offering an individual lament. He is pouring out his complaint before God, begging for mercy from the God of steadfast love. As David pours out his complaint, he imagines death ("For in death there is no remembrance of you") and then, he imagines the realm of Sheol. As he describes Sheol, David does not fear painful punishment, the fire and brimstone of our familiar imagination. No, David fears the absence of praise. "In Sheol," David says, "who will give you praise?"

One might read this complaint as David bargaining with a selfish God. Since God needs praise from his creatures, he would be willing to spare David's life in exchange for an "Hallelujah" now and then. One might read it this way, but one would be wrong. God does not need anything from us "“ indeed, God clarifies that repeatedly in Scripture. He is the Creator and we are his creatures. All that we are and have is already his.

Why, then, does David say this? Perhaps David is remembering what lies at the heart of all of God's creation. The sheer joy of existence "“ as God declares everything he made "good." And that joy, experienced in relationship to God, is praise. God delights in the delight of his creatures not because he needs their delight but because he created them for it. God created all things to rejoice in life, in and with him. For David, Sheol is a terrifying place because it is so far away from God's original design. When imagining that distance, a life so utterly separated from God that he does not give God praise, David laments and cries out for mercy. A mercy that God, in Christ, has freely given to us today.

This biblical view of life is important in ecological conversations. God has created all things to participate in his goodness and to give praise to him. Yet, technological achievements, economic materialism, industrialization, urbanization, and the goal of isolated individual success rather than interdependent communal flourishing have separated people more and more from the created world. In his book, The Paradise of God, Norman Wirzba traces "the steady erosion of the practical and theoretical conditions necessary for the experience of the world as creation."1 For many today, the natural world merely supplies the material that human beings use to create their social spaces and to satisfy their desires (which are often quite a distance from their needs). We have learned to live off creation rather than with it. We see ourselves separate from all other creatures rather than bound together in a world of praise. Technological development and urbanization have so distanced people from creation that they neither fully see nor compassionately care about the created world. And, yet, whether they acknowledge it or not, they are bound in relationship with creation everyday. Lack of this awareness by some could threaten the joy of life for all.

Biblical theology offers Christians a way to engage in this ecological conversation. Rather than call us away from creation, God calls us more deeply into it. His word repeatedly opens our eyes: to see the world around us; to appreciate it as his creation; and to care for it as his handiwork and the community of creatures that he has made our home. When we truly see the world God created, we hear its song of delight "“ the joy of existence "“ and are drawn more deeply into creation's praise.2

Psalm 148 is but one example of the Scriptural witness that calls God's people to see and to hear creation's praise. Here, the psalmist orchestrates the choir of creation. He calls for praise from the heavens (v. 1) and praise from the earth (v. 7). The choir of heaven sings and the choir of earth responds. As the psalmist moves from heaven to earth, he also moves from creation to redemption.

In addressing the heavens, the psalmist notes that they sing praise because "God commanded and they were created . . . he gave a decree and it shall not pass away" (vv. 5-6). Here, we see the continuous creation of God. Creation, itself, leads into praise for God created all things and pronounced them good. To praise is simply to live in the joy of God's continuous creation.

In addressing the earth, the psalmist turns his attention from creation to redemption. After focusing upon humanity, the psalmist notes that they sing praise because God "has raised up a horn for his people . . . for the people of Israel who are near to him" (v. 14). To raise up a horn is to display strength and God has indeed displayed his saving strength when he "raised up a horn of salvation for us in the house of his servant David" (Luke 1:69). In that moment, God came near to his people (Psalm 148:14). Jesus Christ suffered the depths of Sheol for us and rose that he might be the first fruits of a new creation, joining all creatures in the joy of life and an act of praise.

This robust theology of creation's praise is present throughout Scripture. Yet, over the years, the church's awareness of this song of creation has grown quieter. We may praise God for providing us food through creation (at a harvest festival or Thanksgiving) but we rarely gather simply to join in praise with all creation at the goodness of our God. This sermon, like this psalm, seeks to awaken God's people to the wonder of creation once again. It desires to help people see the world anew, to discover delight in the wonder of creation, and through that discovery to join in a robust expression of caring praise.

Sermon Formation:

| Focus | God has prepared a world for us to discover in delight. |

| Function | that the hearers, as God's creatures, join all of all creation in giving God praise. |

| Malady |

sometimes, we limit the language of praise to worship in the congregational setting and we do not see how the world around us fulfills God's creative work by giving him praise. Separated in this way from the world, it is easy to move through the world without seeing it, to limit creation to a doctrinal teaching that is located in the past, and ultimately to overlook the deep wonder God has prepared for us by making us his creatures and surrounding us with a created world that continues to give him praise. |

| Means | the psalmist moves our thoughts from creation (vv. 5-6) to redemption, declaring that God has "raised up a horn for his people" (v. 14). Jesus Christ is the "horn of salvation" that God raised up for us (Luke 1:69). In him, God has taken on human flesh, that he might see the world through our eyes, suffer the punishment for our sinful isolation from the world he created, and rise to become the first fruits of a new creation, that joins together to give God praise. |

| Structure |

the sermon is structured on the basis of a movement from text to application.3 The sermon opens by contrasting the reading from Luke with the psalm. This contrast reveals how the psalmist expands our vision. Rather than only seeing angels praising God the Father for Jesus Christ (Luke 2:13-14), we now see all of creation giving God praise for both creation and redemption. The sermon then walks through the text, noting how the text is divided into a call to the heavens and then a call to the earth for praise. As one moves from heaven to earth, one also moves theological from creation to redemption as the cause of our praise. After walking through the flow of the text, the sermon applies this experience to our daily lives, inviting the hearers to discover the wonder of creation and join in creation's praise. |

- Norman Wirzba, The Paradise of God: Renewing Religion in an Ecological Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 61-62. For the full richness of his argument, read "Chapter 2: Culture as the Denial of Creation," 61-92.

- For a theological elaboration on creation's praise in the context of Sabbath rest, see Charles Arand's work in Together with All Creatures: Caring for God's Living Earth. A Report of the Commission of Theology and Church Relations. The Lutheran Church "“ Missouri Synod (St. Louis: CPH, 2010), 106-113.

- For a description of this structure, see the information posted on this sermon structure located at The Pulpit on concordiatheology.org. See http://concordiatheology.org/sermon-structs/textual/text-application/.

II: Discovering Delight in the Wonder of Creation

Picture the sky at night in Judea. Before electricity. Before smog. Before our cars and our industry separated us from the heavens, surrounding us with a polluted haze. Before all of that, picture yourself looking at the stars at night in Judea. The dark sky is darker somehow without a city's glow. And the bright stars shine brighter somehow without a city's haze. You see something wonderful. More stars than you knew. Shining brighter than you thought stars could shine. You see something wonderful, but then God makes it something more wonderful still. For those shepherds watching their flocks outside of Bethlehem, God revealed his angels. A choir of angels singing praise. As Luke tells us in his gospel, God peeled back the thin veil of our world that hides the invisible from the visible and he opened up the nighttime sky. The shepherds saw an army of angels, shining brighter than any star. "The glory of the Lord shone around them" (Luke 2:9). And these angels lifted their voices rather than their swords, singing praise to God: "Glory to God in the highest and peace to his people on earth" (2:14). Discovering Delight in the Wonder of Creation

Addenda

| First Reading | Psalm 148 |

| Second Reading | Luke 2:8-19 |

| Hymnody |

LSB 795 "Voices Raised to You We Offer" |

| Collect | Heavenly Father, you raised your Son Jesus Christ from the dead that we might have a glorious hope in him, Draw us deeper into your word and into the world you created, that we might live here in repentant hope, humbly confessing our sin and eagerly longing for your new creation, as we care for your broken beautiful world. Through Jesus Christ, your Son, our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen. |

Part Three

Sermon Study

Biblical Theology and Ecology:

Have you noticed how grocery stores are being transformed? With the proliferation of farmer's markets and the development of an ecological consciousness, grocery stores are becoming grocery stories.

You go to the produce section and there, above the corn, is a small sign with a map and a picture. You can see the place where your food was grown, the farmer who produced your food, and, in the accompanying description, you can read about the farm. Its history or agricultural practices. Behind four ears of corn, tightly wrapped in cellophane, there is a story. A story of how the food that you eat was brought to you from the world you live in. Near the door of the store is a barrel asking for your used plastic bags and, nearby, a stand that provides reusable cloth bags for sale. A sign here offers you another story, a story of where the waste that you produce ends up in the world. As you walk into a grocery store, therefore, you are no longer simply in a place that provides commodities for purchase. Instead, you are drawn into a community. You have moved from commodity to community, from resources to relationships. You begin to see how the food you eat comes from the larger world you live in and how the waste you produce returns to the world once again. Grocery stores have become grocery stories and the question is "where does the church fit into this ecological conversation? What story do we have to tell?"

For some Christians, the question itself is odd. Our attention has been focused on mission. Saving souls not trees. Caring for people not animals. To even begin the conversation seems strange. It appears as if the church is somehow selling out to a political agenda, letting the environmental movement dictate our theological conversation. Yet, you don't have to read very far in the bible (try starting at Genesis 1!) to find out that God indeed is involved in an ecological conversation with his people. Scripture is filled with the language of God's creation of the world and his care for the world that he has created. So deep is that love, so certain is that goodness, that the future life is not pictured as a disembodied existence. Rather, Jesus rises in his body, the first fruits of a new creation. God promises us a new heaven and a new earth and eternal life in glorified bodies. Does the conversation seem strange? That's simply because the church has not talked about God's care of creation enough over the years. But Scripture is filled with resources that enable us to enter into this ecological conversation.

Beginning the conversation can be hard, however. This is primarily because the voices that are calling for care of creation often do so without an appreciation of the Christian story. Christianity, itself, has been seen as part of the problem. The popular evolutionary biologist and atheist, Richard Dawkins has attributed to Christianity the ideological crime of speciesism: separating the human species from other species and thereby making it possible to do things to other species that one would not do to the human species. In his book The Blind Watchmaker, Dawkins describes "the breathtaking speciesism of our Christian-inspired attitudes": "the abortion of a single human zygote (most of them are destined to be spontaneously aborted anyway) can arouse more moral solicitude and righteous indignation than the vivisection of any number of intelligent adult chimpanzees!"1 Peter Singer, a professor of bioethics at Princeton University and animal rights activist, claims that the Judeo-Christian tradition is a fundamental problem for the animal rights movement. The Genesis account is a "myth to make human beings feel their supremacy and their power" and results in "species-selfishness."2 When the Christian story has been so ostracized and demonized in the cause of care for creation, Christians can mishear even one another. A Christian who speaks about care for the treatment of animals suddenly sounds political and the church can develop an overemphasis on the language of human dominion in order to counteract the cultural denial of the word of God. Suddenly, the church is divided between those who speak about care for creation and those who advocate human dominion, while the majority of believers try to avoid such conversations and turn their attention to subjects about which we can all agree: seeking to save the lost.

Scripture, itself, however, invites us into the conversation and provides us with the language to speak. In reading Genesis 9, one discovers a delicate balance between what could be called care and consumption. At the heart of Genesis 9 lies God's value of life. All of life. God cares for life in several ways: (1) in the reiteration of the original command to Adam and Eve to "be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth" (9:1); (2) in the direction not to eat meat with its blood in it, for "its blood" is "its life" and life belongs to God (9:4; cf. Lev. 17:10-14); (3) in the protection of human life (9:6); and (4) in God's covenant established not only with Noah but with all living creatures (a fact repeatedly emphasized in 9:10, 12, 13, 15, 16), a covenant to never again destroy the earth through flooding. The text overflows with God's care for life.

At the same time, however, the text expands the complexity of the human experience as a creature caring for God's other creatures. In contrast to Genesis 1:29, God gives Noah and his descendants animals for food (9:2-4). In doing this, God places fear of humans in the hearts of his creatures (9:2) even as he entrusts these creatures to the human community for consumption (9:2-4). The human being, therefore, is always in a position of tension. The tension of caring consumption. On the one hand, as a steward of God's creation and as one who knows how God values life, the human creature cares for other creatures in order that creation might flourish according to God's original design. On the other hand, as a recipient of God's care, the human being also receives the gift of animals for food, knowing that God provides this means for his creatures to sustain life. God's people, therefore, care for creation even as they consume of it. Both are recognized to be part of God's good design and acknowledged as God's gift.

Thus, Christians have a God-given interest in the care of animals. They seek to help them flourish and can explore with faithful responsibility the ecological effects of patterns of human consumption. The grocery store, for Christians, is more than a place to purchase goods. It is a place where Christians can confess the goodness of creation. Changing how we see things, examining our purchasing habits, moving our conversation from the goods of creation to the goodness of creation, from resources to relationships, from commodities to community, are part of a faithful responsible witness. Some Christians articulate this care for animals in a way that calls for vegetarianism as the most responsible form of Christian living.3 This sermon does otherwise. Building on God's gift of animals for consumption in Genesis 9:2-4, this sermon calls for a compassionate treatment of the animals that God has given us for food.4 It seeks to articulate that tension wherein we do not deny God's gift of animals for consumption but we also do not overemphasize that gift to the point where animals are no longer cared for as they are processed and packaged for consumption.5 God calls us to live within the delicate balance of a faithful responsible caring consumption.6

The book of Jonah has what might be considered the strangest ending of all of the prophetic books: ". . . and also much cattle?" (Jonah 4:11). God has sent Jonah in mission to call the people of Nineveh to repentance. After recounting Jonah's resistance and ultimate obedience, the book brings the reader to the end of the story. Not just the salvation of the people of Nineveh, but something more. At the end of the story, as God reveals his great missionary compassion to his reluctant prophet, God suddenly expands Jonah's vision. God speaks of his pity for the people of Nineveh: "and should not I pity Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than 120,000 persons who do not know their right hand from their left" (4:11). But then, God expands his vision to include even creation itself: "and also much cattle" (4:11). The mission of God has suddenly been transformed from saving human lives to caring for creatures as well.

A similar transformation is happening in the following sermon. The sermon seeks to expand the church's vision from the covenant with Abraham, wherein God will bless all nations through him (Gen. 12:1-3), to the covenant with Noah (Gen. 9:1-17). Here, the church suddenly sees another gracious working of God. His care for all of creation. Historically, the church has been deeply engaged in missiological witness. Our members are accustomed to hearing sermons that encourage them to witness to others about salvation in Jesus Christ. And congregations have engaged in demographic studies, knowing in great detail the people of their neighborhood. This sermon, for a moment, suggests that we broaden our vision. That, in addition to people, we manifest God's concern for "much cattle." Imagine a congregation engaged in an ecological study, considering their contribution as Christians in that location to the community of created life.7 For some, this will sound as strange as God's words to Jonah. For others, however, it will help them honor the good design of God.

The goal of this sermon is that God's people participate in a faithful and responsible practice of caring consumption. Since this aspect of discipleship is appreciated in various ways in various congregations, the preacher will want to be discerning in how he uses the material presented here for a sermon. Some communities may be pushed deeper into a concrete examination of their practices of consumption; while other communities may only begin considering this faithful expression of the life that God desires. The goal, here, is to gain a hearing: to proclaim God's word faithfully in a way that does not unnecessarily offend. By doing this, you will help the church enter into the larger ecological conversation of our culture and discover that God has given the church a voice, along with a life of witness to share with and for the world.

Sermon Formation:

| Focus | God values all life and calls us to a life of caring consumption in his creation. |

| Function | that the hearers live in caring consumption. As God's people, we are mindful of God's covenant with all creatures and demonstrate a faithful responsibility toward the created world. |

| Malady | although God has called us to a life of caring consumption, we fail to live in his good design.

On the one hand, we at times deny the care of creation. In this case, we live solely in terms of consumption. We see the world as full of resources to be used and overlook the way God has filled the world with relationships to be cultivated. We reduce our world to commodities for our use and remain blind to the community of God's creatures. On the other hand, we at times also deny the consumption of that which God has given for our use. Environmental activists can be so drawn into the care of creation that they deny God has given animals to the human creature for food. Such claims, they argue, are a form of speciesism or human exceptionalism. |

| Means | Christ manifested God's value of life by valuing our lives. When seeing us in our sin, he offered his life for ours. In his death upon the cross, he shed his blood for all people and in his resurrection he calls us to live as witnesses of God's good design, careful stewards of God's gift of creation. |

| Structure |

the sermon uses an image to create a frame-and-refrain design.8 The sermon opens with an image that will frame the whole sermon: the image of a mayfly in the palm of a child's hand surrounded by a rainbow. This image leads the hearers to the refrain that structures the flow of the sermon: "God has placed that which he treasures into our hands and invites us into a life of caring consumption." The sermon then anchors this teaching in the text from Genesis, revealing how God established a covenant with all living creatures after the flood and called humans into a life of caring consumption in his creation. The sermon then explores this teaching in relation to our lives, moving from repentance for times that we fail to exercise caring consumption to our forgiveness in Christ, and then to envisioning the new life that Christ brings us in his resurrection. The sermon then closes by returning to the image and meditating upon the work of God, calling us into a life of faithful responsibility as creatures in the community of his creation. |

- Richard Dawkins, The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe without Design (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1986), 263.

- Peter Singer, "Prologue: Ethics and the New Animal Liberation Movement" in In Defense of Animals, ed. Peter Singer (New York: Basil Blackwell, 1985), 2-4.

- See Stephen R. Kaufman and Nathan Braum, Good News for All Creation: Vegetarianism as Christian Stewardship (Cleveland: Vegetarian Advocates Press, 2004) and Richard A. Young, Is God a Vegetarian? Christianity, Vegetarianism, and Animal Rights (Chicago: Open Court Publishing Company, 1998), and Stephen H. Webb, Good Eating (The Christian Practice of Everyday Life) (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2001).

- For a helpful defense of meat consumption within the Catholic tradition, see Beth K. Haile, "Virtuous Meat Consumption: A Virtue Ethics Defense of an Omnivorous Way of Life" in Logos 16.1 (Winter 2013): 83-100.

- This is not an easy task, as Beth Haile notes in her article (see previous citation), considering that "In 2008, 17,328,000 cattle, 4,590,314,000 chickens, and 57,542,000 hogs were slaughtered for food" (Haile, 85).

- For a theological elaboration on the tension of caring consumption, see Charles Arand's work in Together with All Creatures: Caring for God's Living Earth. A Report of the Commission of Theology and Church Relations. The Lutheran Church "“ Missouri Synod (St. Louis: CPH, 2010), 83-99.

- Gilson A. C. Waldkoenig offers some very concrete examples of such congregational activities in his article calling churches to enter into this ecological conversation. See Gilson A. C. Waldkoenig, "From Commodity to Community: Churches and the Land They Own," in The Cresset (Trinity 2013): 19-25. The article may be accessed at http://thecresset.org/2013/Trinity/Waldkoenig_T13.html. Accessed August 14, 2013.

- For a description of this structure, see the information posted on this sermon structure located at The Pulpit on concordiatheology.org. See http://concordiatheology.org/sermon-structs/dynamic/imagistic-structures/frame-refrain/

III: Living in Caring Consumption

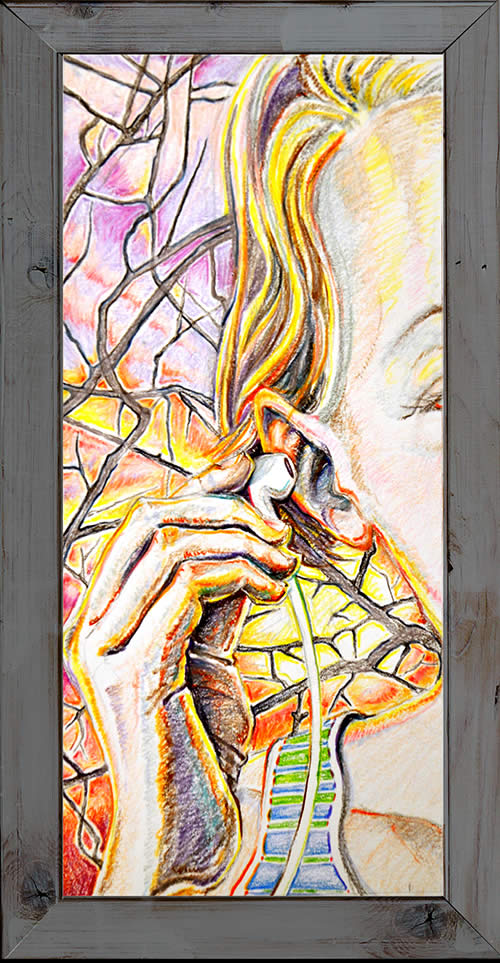

Life passes by so quickly that sometimes we need people to help us see. Truly see what is happening around us. Artists can do that. They can pick up their paper and pencil and capture a moment. Sketch it so that we can see it. And seeing it, appreciate it. Consider the drawing by Karl Fay for our sermon this morning. Take a moment to look at the creature that rests in the palm of a hand. It's a mayfly. And mayflies are momentary. They are creatures of the moment. Born in the water, they swim to a rock or a plant. There, they grow wings and fly to another location only to molt again into adults. Once they are adults, they live only a day or two. Their mouths are actually non-functional. They do not need to eat. For they live only briefly. They live. They fly. They mate. They die. In a day or two at the most. And yet, there it is. A mayfly. In the palm of a hand. It wasn't there yesterday. It won't be there tomorrow. But for now, someone holds this creature and is drawn into the momentary wonder of God's creation. Living in Caring Consumption

Addenda

| First Reading | Genesis 9:1-17 |

| Second Reading | John 21:1-14 |

| Hymnody |

LSB 782 "Gracious God, You Send Great Blessings" |

| Collect | Father Almighty, Maker of Heaven and Earth, you value all life and in love made a covenant with your creation, Teach us to live faithfully and responsibly as part of a community of creatures, your peaceable kingdom, so that we might exercise care in our consumption of all the gifts you so graciously give, Through Jesus Christ, your Son, our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen. |

Part Four

Sermon Study

Biblical Theology and Ecology:

This series of sermons has sought to help the church awaken to the wonder of God's work in creation. At times, it seems as if the story of salvation has been truncated in the church. Rather than proclaim the biblical story from creation to the new creation, the church proclaims the fall into sin and the death of Jesus for the forgiveness of sins. With such a truncated story, it is easy for people to lose sight of their bodies and of the world they live in. In this shortened version, what matters most are our souls and the salvation of our souls by the death of Jesus. Yet, when Jesus rose from the dead, he rose with his body and, when the apostle Paul speaks about the good news of salvation, he speaks about "the redemption of our bodies" and the renewal of all creation, finally "set free from its bondage to corruption" (Romans 8:18-24). This sermon series has sought to proclaim the fullness of the Christian story with the goal that God's people will enter more richly and intentionally into their God-given vocation of care for the created world. The series has anchored our care of creation in Christ, the Second Adam, ruling over all things (sermon 1) and encouraged God's people to discover delight in the wonder of creation (sermon 2) and participate faithfully and responsibly in the stewardship of creation (sermon 3).

During the course of this sermons series, perhaps members of your congregation have initiated projects as part of their care for creation. That's good. Unfortunately, it is also difficult to sustain such work over time. While it is relatively easy to be struck by the wonder of God's beautiful creation, it doesn't take long until one begins to see a darker side. Watch the nature channel for too long and you will soon see death and dismemberment. Watch the weather channel for too long and you will soon see the horrifying effects of floods and drought, earthquakes and tornados. Livable land turned into waste places. Although created good by God, creation has suffered effects from the fall into sin. God cursed the ground (Gen. 3:18) and the forces of nature at times fight against human flourishing. In pain, we eat from the ground until we return to it.

Distress doesn't only arise from a closer look at nature, however. Consider what happens when your people take a closer look at what humanity has done to their natural world. The statistics are staggering: roughly 805 million people are undernourished in the world (that would be a line of people encircling the globe 13 times); over 50 percent of people do not have an adequate supply of water; three species of plant or animal life become extinct every day; 25 million acres of tropical forest are destroyed every year (roughly the size of Indiana); a convoy of garbage trucks carrying only one year's worth of garbage from the United States alone would encircle the globe 3.8 times; and this is not to mention matters of energy consumption, air pollution, and a host of other ecological difficulties.1

When God's people begin to care for creation, they suddenly face sobering statistics and sense the insignificance of their local efforts when faced with large-scale patterns of consumption and profitable corporate industries that both inspire and satisfy those consumer desires. It is easy for a Christian to move from being in awe with the wonder of God's creation (sermon 2) to seeking to live in caring consumption (sermon 3) to suddenly feeling angry or depressed, suffering from compassion fatigue.2 Many disciples get lost in that gap between the simplicity of our individual efforts and the complexity of the world's ecological problems. Care for creation becomes a program they try and find too taxing, not a way of life that God has given them in Christ.

For that reason, this last sermon in the series seeks to foster a larger spiritual vision for God's people, a vision that will sustain them in the midst of the painful realities of our ecological situation. This vision is anchored in Paul's words to the Roman Christians. In Romans 8, Paul depicts life in the Spirit. Yet, he does not focus upon a disembodied experience, a movement from physical to spiritual, from body to soul, from earth to heaven. Instead, Paul grounds the spiritual life in the experience of a very physical hope: hope for the redemption of our bodies and for the release of creation from its bondage to decay. Paul's vision has two qualities to it that are helpful for Christians engaged in ecological efforts and conversation.

First, Paul is honest about the suffering of creation. Echoing language from the psalms and prophets, Paul listens to the voices of creation. Only instead of unmitigated praise, Paul hears groaning. Creation cries in eager anticipation for the return of Christ, the revelation of the sons of God, the dawn of a new creation when the created world will finally be released from its bondage to futility that occurred as a result of the fall. With that in mind, Christians are able to face the horrors of creation's bondage with sobering honesty. When seeing such things, they are led to repentance. They model for others how individuals mourn their fall from God's good design, confess their sins, and turn to God for forgiveness and gracious redirection in manifesting his good design in this fallen world.

Second, this repentance is joined to hope. As Paul listens to the groans of creation, he hears not only cries of suffering but also cries of expectation: he calls these groans the pains of childbirth that anticipate new life. Christians join creation in this eager hope. We long for the redemption of our bodies and the dawn of the new creation. Our efforts in caring for creation, then, are not silenced by the horrors of ecological disaster. They are not diminished to despair by the complexity of the world. They are not fueled by trust in our technological progress. Rather they are driven by hope. Hope in our risen Lord who now rules over all things and promises to return, raise our physical bodies, and bring about a new creation. In eager anticipation of that new creation, we live in a repentant hope, confessing our sin and caring for God's gift of this broken beautiful world.

The closing sermon of this series, therefore, seeks to strengthen Christians for the life-long task of caring for God's world. It anchors that strength in our risen Savior and his promise to bring about a new creation and encourages God's people to manifest that strength in lives of repentant hope. Though the suffering of creation is overwhelming, the Christian can face it soberly and honestly: we repent of sin and yet do not despair, because we have a sure and certain glorious hope that strengthens our service until our Savior returns.3

Sermon Formation

| Focus | Christ will bring about a new creation. |

| Function | that the hearers may live in repentant hope. As God's people, we are mindful of our sin and repent of the damage that we cause to creation but we are also mindful of God's grace and care for creation in repentant hope of the restoration of all things. |

| Malady | we can sometimes tune out the world around us and live detached from creation, immersed in a world of our own technological creation. When God awakens us to the reality of our lives as his creatures in community with his larger creation, our lives can be overwhelmed with the horror of what we discover. Rather than repent of our sin and seek to live in a faithful responsible care for creation, we get angry or we suffer from compassion fatigue, fall into despair, and give up hope. |

| Means | in death, Christ freed us from our sin and in his resurrection he brings us a glorious hope of a new creation. He is the first fruits of the new creation, the risen Gardener who has come to care for his world. Because of his resurrection, ascension, and rule over all things, we join creation in an expectant hope of the redemption of our bodies and the release of creation from its bondage to corruption. |

| Structure |

the sermon uses a thematic structure to lead the hearers through the logic of Paul's text.4 Paul's argument in Romans immerses us in the world where we hear the groans of creation, discover the rule of our resurrected Lord, and live in repentant hope. Using a thematic structure of cause-effect,5 the sermon will treat each of these ideas in a separate section. For each section, the hearers will consider how this teaching is anchored in the text and then applied in their lives. The sermon thus leads hearers through this theological teaching by proclaiming how it is based on the text and then applied in their lives. |

- These and other statistics are available in Steven Bouma-Prediger's sobering chapter on the state of the planet, "What's Wrong with the World," in Steven Bouma-Prediger, For the Beauty of the Earth: A Christian Vision for Creation Care (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2010), 23-55.

- For more on compassion fatigue, see compassionfatigue.org. Accessed August 15, 2013.

- For a theological elaboration on the restoration of all things in the new creation, see Charles Arand's work in Together with All Creatures: Caring for God's Living Earth. A Report of the Commission of Theology and Church Relations. The Lutheran Church "“ Missouri Synod (St. Louis: CPH, 2010), 36-38.

- For a description of thematic preaching, see the information posted at The Pulpit on concordiatheology.org. See concordiatheology.org/sermon-structs/thematic/.

- For a description of this specific structure, see concordiatheology.org/sermon-structs/thematic/causeeffect/.

IV: Living in Repentant Hope

Henry Vaughan was a devotional poet in the seventeenth century. And he wrote a poem about reading Scripture. It's called "The Book." What's interesting about this poem is what Vaughan sees when he opens the bible. Vaughan sees more than words on a page. He sees the pages themselves. At the time when Vaughan was writing, paper production was not as refined as it is today. If you looked closely, you could tell what your paper was made of. If the spring waters of the river ran muddy, the paper was discolored because of it. There were flecks and fibers embedded in the page. Strands of hair. Pieces of feather. A vegetable fiber. These would appear right next to the printed word. So, when Vaughan opened his bible he saw the world. He saw plants that the paper was made from, trees that contributed wood to the backing, animal skin that made the leather binding. Opening the bible, he saw the world. Living in Redundant Hope

Addenda

| First Reading | Romans 8:18-24 |

| Second Reading | John 20:11-18 |

| Hymnody |

LSB 792 "New Songs of Celebration Render" |

| Collect | Heavenly Father, you raised your Son Jesus Christ from the dead that we might have a glorious hope in him, Draw us deeper into your word and into the world you created, that we might live here in repentant hope, humbly confessing our sin and eagerly longing for your new creation, as we care for your broken beautiful world. Through Jesus Christ, your Son, our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen. |