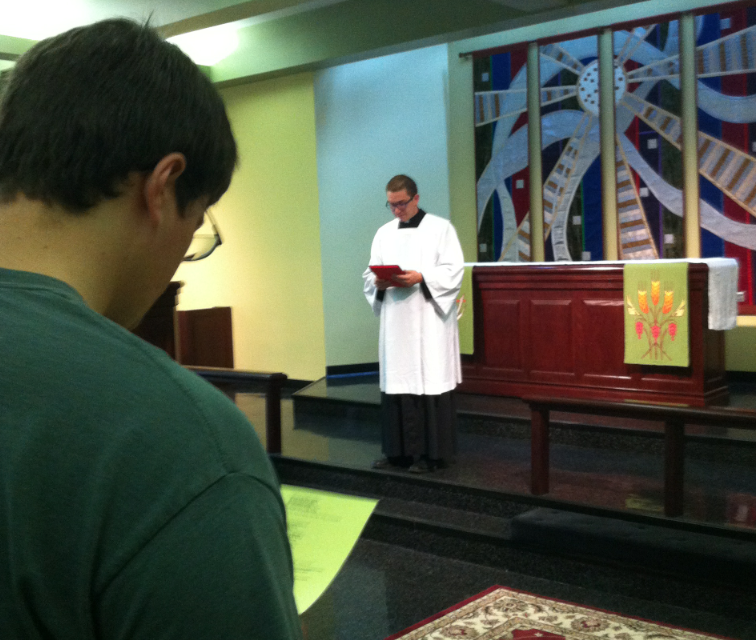

In chapel this week—in mid-August, chapel is held in the undercroft because the only students on campus are those finishing Summer Greek—the liturgist did something I have not seen heretofore: he led the liturgy from an electronic “tablet.” What, as someone has said, does this mean? A couple of thoughts. First, my good friend and colleague Andy Bartelt has observed that a move to computer screens is effectively a return to the scroll, away from the codex. This is an interesting and far-reaching thought. The codex, as is now generally accepted, was a “technology” embraced almost immediately by Christians, and in such a way that Christian documents are from the first almost media-wise different from secular documents, which still almost universally employed scrolls. The codex allows very quick cross-referencing (which may be why it was adopted), and it is very “handy.” To return to a “scroll” format, is, essentially, to give up much of the advantage of the codex, such as flipping back and forth between sections of a book almost instantly. It is for this reason that I, for one, find it difficult to compose really serious pieces solely on a computer; it does not allow for quick moves between different pieces of writing.

In chapel this week—in mid-August, chapel is held in the undercroft because the only students on campus are those finishing Summer Greek—the liturgist did something I have not seen heretofore: he led the liturgy from an electronic “tablet.” What, as someone has said, does this mean? A couple of thoughts. First, my good friend and colleague Andy Bartelt has observed that a move to computer screens is effectively a return to the scroll, away from the codex. This is an interesting and far-reaching thought. The codex, as is now generally accepted, was a “technology” embraced almost immediately by Christians, and in such a way that Christian documents are from the first almost media-wise different from secular documents, which still almost universally employed scrolls. The codex allows very quick cross-referencing (which may be why it was adopted), and it is very “handy.” To return to a “scroll” format, is, essentially, to give up much of the advantage of the codex, such as flipping back and forth between sections of a book almost instantly. It is for this reason that I, for one, find it difficult to compose really serious pieces solely on a computer; it does not allow for quick moves between different pieces of writing.

Second, and more important, is the matter of hermeneutics. Almost 30 years ago (1987), Tom Boomershine presented a paper at the national meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in Boston entitled “Biblical Megatrends: Towards a Paradigm for the Interpretation of the Bible in Electronic Media.” In this essay he stated: “…the expectation would be that major changes in communications systems are followed by paradigm shifts in Biblical interpretation.” He went on to observe that in an oral culture there was improvisation on known formulas, which provided a way of connecting present and past “by retelling or representing the material in light of later experiences.” When writing started to be prominent in the Hellenistic world (though it first was used in the service of orality), the text began to be standardized, and, as a result, a hermeneutical shift took place, especially within Christianity. Allegorical interpretation arose as a means to make the words of the texts relevant to the contemporary context. Another shift occurred with the advent of the printing press, which is something other than manuscript production. Now exact copies were possible and widely distributed. Hermeneutically, private reading and study of texts became possible, and literal/figural exegesis became dominant (cf. the rise of humanism). In the 19th century historical criticism also arose, with the texts of several authors able easily to be compared in minute detail, and such texts were increasingly seen as valuable chiefly as documentary evidence for historical facts or for ideas (see Hans Frei, The Eclipse of Biblical Narrative, whom Boomershine helpfully references). What does the current shift to electronic media suggest? Boomershine is not all that confident to say in detail. But he does observe that one thing seems sure: there is a move away from silent reading, and study without sound, as it were. This leads us back to a context of orality—hence Walter Ong’s concept of “secondary orality”—and to the characteristics of that milieu, including both its strengths and its weaknesses. And what will that mean? Personally, there’s a lot to be positive about, especially since the fundamental command to God’s people was “Hear [not See, or Think About, or Contemplate], O Israel….” (Deut. 6:4). And the Apostle teaches that “Faith comes through hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ (Rom. 10:17). Perhaps this is why, on the death bed, hearing is the last sense to be lost.

We have to be serious about developments like this. It’s not just “new technology.” We may lose some things, but we may also gain some things for the hearing of the Gospel.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.