Last Friday, chapel was unusual; it took me off guard. First, I did not expect to sing Christmas hymns … in the middle of Lent. Yes, I have to admit that I wasn’t paying attention to the feast day calendar so I missed the liturgical memo on the Annunciation of our Lord. It was a welcome surprise nonetheless, and the juxtaposition of the prenatal promise with the season’s culmination of passion and death led me to consider our Lord’s great love from a fresh perspective.

But it was the readings that were particularly striking—especially the Gospel lection from Luke 1. Remarkably, the lector spoke two languages simultaneously: English … and American Sign Language. The result was an encounter with the Word of God that engaged several of my senses at once. First, the reading was slower, more deliberate than usual, as the lector timed the motions of his hands with the spoken words. The pauses between phrases, which were longer, somehow heightened my interest and attention, my ears perhaps becoming restless to hear what would follow. Of course it was a familiar text, but ensconced in two forms I heard it anew. For example, in verse 31, “And behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus,” the sign for “womb” and “Jesus” immediately brought our Lord’s birth and death together as the hands of the lector made a circle around an imaginary belly and then moved up to touch the palms, placing a finger on invisible wounds left from cruel nails.

It occurred to me that this experience is similar to what can happen when the Scriptures are chanted, especially familiar texts like the evangelists’ account of the Passion of our Lord. Over ten years ago, James Brauer, then Dean of the Chapel, asked me to chant the Passion according to the Gospel of Mark in the seminary chapel for the Monday of Holy Week. I have continued to do this every year since, cycling through the lectionary’s evangelists several times round. Personally, it has been a wonderful experience and an ongoing experiment as I’ve attempted to bring text and melody together as two “languages” that simultaneously speak of the story of salvation and perhaps strike the ear—and faith (fides ex auditu!)—in a new way.

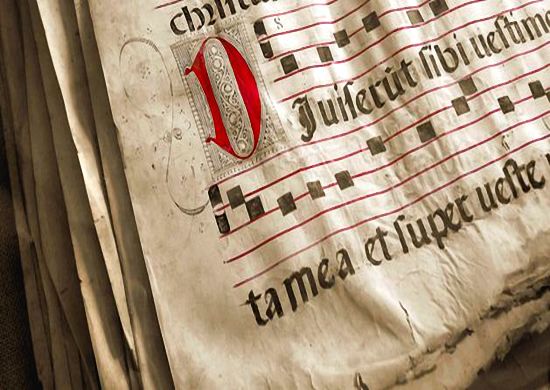

Actually, it isn’t very new. The church has sung the lectionary for centuries. Why? Well, first of all … no microphones. Perhaps it was not the only reason, but singing the Scriptures projected the text in spaces and crowds that would otherwise swallow it up. But beyond pragmatics, singing slowed things down and through the inflection of tone interpreted the text for the hearer … the music, in effect, participated in proclamation. Tonal cues would reinforce the textual change from narrator to a speaker within the narrative, or from the questions of the crowd to the instruction of our Lord. The double “voice” of text and music could bring subtle consensus or jarring juxtapositions, providing additional opportunities for reflection and hearing the Word of God again. It probably didn’t always work like my romantic description … but undoubtedly sometimes it did. With advanced sound systems we don’t need music to project our readings anymore, but there are other reasons—reasons that touch on the edification of our people—to consider trying this occasionally. I have found that the Passion of our Lord serves as a perfect occasion.

So, let me share with you a little of what I have tried to do with this over the last decade, in case you are interested in trying it. You can download a PDF of this year’s Passion Narrative from the Gospel of Matthew with my notations. And we have also provided a link to one of the past recordings from chapel, from the Gospel of Mark, as an example. There are various logical boundaries for the Passion Narrative—I have always begun with the inquiry of Pontius Pilate and ended with the burial of Jesus.

First, I use Martin Luther’s revision of the Gospel tone in his German Mass from 1526 (LW 53, 53f.). Luther was especially interested in having music participate in proclamation and was very thoughtful in how the tone ought to interact with the text to do just that. Though he relied on the traditional modes of plainsong, he strove to make them more “melodious” with a greater range and small changes that simply sounded better to his ear. He even mixed modes together so that the words of Christ would be more beautiful, a rationale that his assistant Johann Walter recalled, “for Christ is a kind Lord and his words are sweet.” Luther suggested that the Words of Institution and the reading of the Gospel ought to be sung to the same mode so that musically the evangelical character of the Lord’s Supper would be reinforced.

Luther’s flexibility in service to the text is especially instructive, and has guided much of what I’ve done with the Passion over the years. He was very concerned about the negative effects of forcing Latin musical forms whole cloth on a German text with no regard for the cadence of the language: “the text and notes, accent, melody, and manner of rendering ought to grow out of the true mother tongue and its inflection, otherwise all of it becomes an imitation in the manner of apes” (LW 40, 141). While he gave instruction for various endings and terminations—period, question, comma, colon—he wanted the text and the natural accents of the language to dictate how this was implemented. I would suggest doing the same thing when applying these tones to an English text. Over the years, I have changed the pointing to reflect the emphasis and cadence of English (and I will probably keep making minor changes).

Now to the singing. The most helpful comments to me have been those that have added caution to affirmation. If my musical choices, dramatic pauses, or changes in tempo and volume draw the hearer’s attention to me, then I’ve gone too far. But if I just lovelessly drone on, the second voice of music hides the first voice of the text … it’s 10 minuets of “clanging gong.” A little preparation—thinking about the texture and emphasis of the narrative, its climax, its recurring themes—goes a long way. For example, at the end of the narrative we have various accounts of the burial of Jesus. Following the apparent tragedy of Jesus’ death and the drama of nature’s turmoil, I imagine that the followers of Jesus are simply numb with grief. The narrative goes on, but the actions are monotonous and without feeling, even as a mourner might just go through the necessary motions: “Joseph took the body … and wrapped it in a clean linen shroud … and laid it in his own new tomb … which he had cut in the rock … and he rolled a great stone to the entrance of the tomb … and went away.” So I’ve tried to sing it in this way—soft, steady, with the pulse of monotony—a purposeful purposelessness.

Most of my attempts have been by myself, but last year we used two other voices—a tenor for the individual voices and the crowd, and a bass for the voice of Jesus (I continued as the voice of the evangelist). This worked really well, especially since it was the Gospel of Luke, and we will try something similar this year with Matthew. Again, the challenge is to present the narrative of our Lord’s Passion for the sake of the hearer and not make a spectacle of ourselves.

Well, this was a longer post than I had anticipated but I hope some of it is helpful. I’d be interested in your thoughts and hearing how it goes if you try chanting the Passion this year. Obviously, all of this falls under Christian liberty, but as Luther notes, within this liberty such things ought not simply come from an “itch to produce something novel” so that we “shine before men as leading lights,” but rather it should only be used “for the glory of God and the good of the neighbor … freedom shall be and remain a servant of love and of our fellow-man.” With this in mind, I pray that your proclamation of the Lord’s Passion strikes the ear and heart of God’s people once again.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.