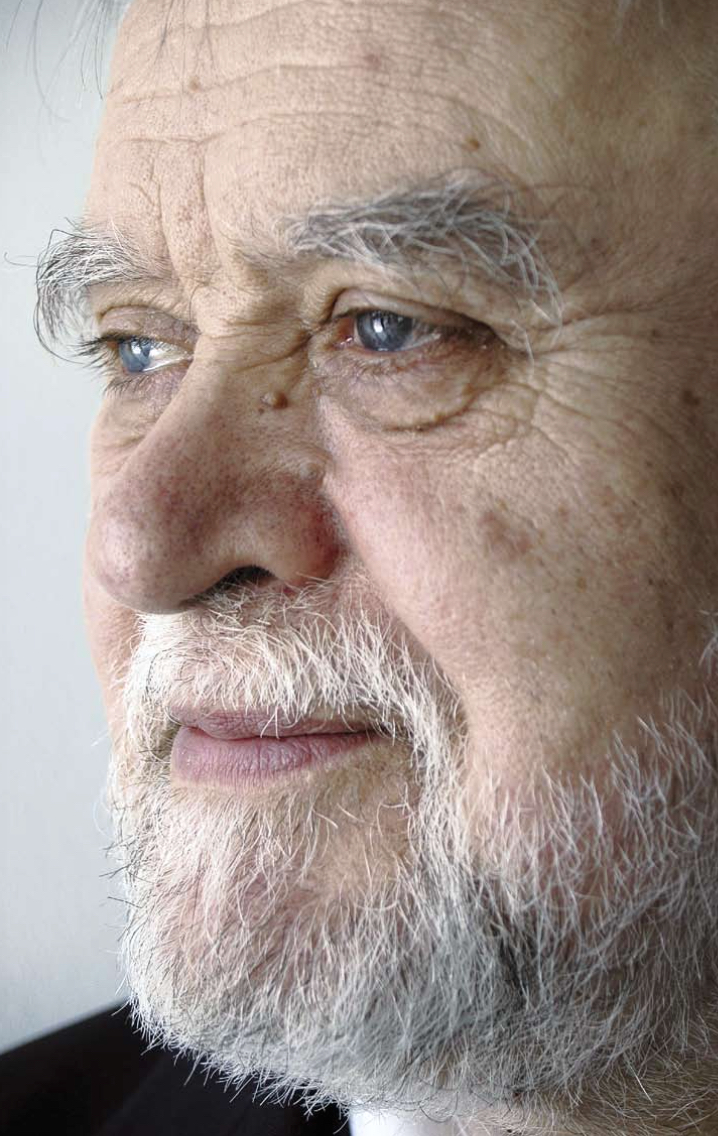

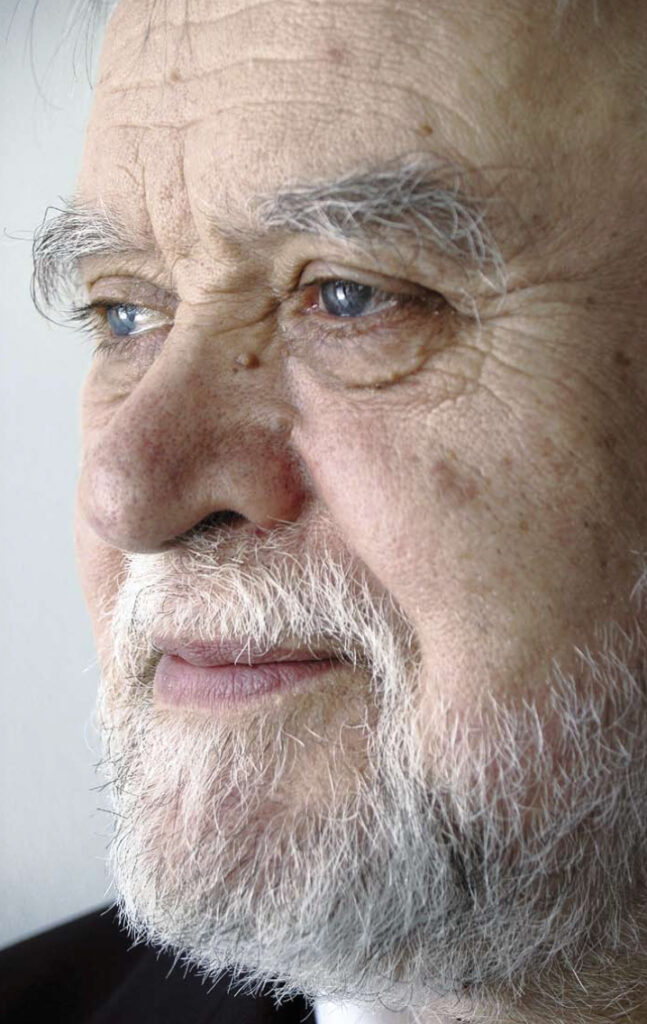

Tuomo Mannermaa (September 29,1937-January 19, 2015), professor emeritus of ecumenical Theology at the University of Helsinki and internationally recognized Luther scholar, died this past week at age 77. Born in Oulu, Finland, he studied at the University of Helsinki and held professorships in social ethics (1972-1976) and systematic theology (1974-1980), before assuming the chair of ecumenical theology in 1980. His participation in ecumenical dialogues, particularly with Eastern Orthodox theologians, led to his accentuation of elements in Luther’s writings that he found akin to the Orthodox doctrine of salvation through theosis (divinization). His most prominent North American student, Kirsi Stjerna, professor of church history at Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, summed up his position in her tribute to her mentor at his death: “Known as the father of the “Finnish Interpretation of Luther”, Professor Mannermaa in the 1980s introduced a hermeneutical paradigm shift in the reading of Luther’s doctrine of justification by unfolding the centrality of the effective righteousness in Luther’s theology of salvation. Based on his close examination of Luther’s interpretation of St. Paul’s letters, he discovered the under-appreciated dimension of Luther’s central theology: the ‘real-ontic’ indwelling of Christ in faith, and the essential connection between love and faith. The ecumenical promise of the connections made between Luther’s ideas of ‘Christ present in faith’ and the patristic notion of ‘divinization’ continues to generate new studies with different methodologies and premises.” Mannermaa also authored popular devotional books in Finnish. His seminar created a school of scholars who have contributed a wide range of studies of various aspects of Luther’s thought. His ideas have influenced students of the Reformation around the world and continue to arouse debate. His impact on Luther research will remain a focus of discussion for the years to come.

In Memoriam. By Robert Kolb

It was a friend from Hannover, a Landeskirche pastor named Ulrich Asendorf, whom I had met at Concordia Theological Seminary in Fort Wayne, where he sometimes served as guest professor, that I first heard the name “Tuomo Mannermaa.” As we drove together across the north German plain in 1987, Asendorf asked me if I did not think that the authors of the Formula of Concord had treated Andreas Osiander unfairly in condemning his definition of justification of faith. Osiander had taught that the righteousness that avails before God is the indwelling divine nature of Christ, who comes into the believer through faith. Asendorf explained that he and Mannermaa had become friends through their common opposition to the Leuenberg Concord of 1973, the consensus document with which Lutherans and Reformed in Germany addressed the doctrine of the true presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper.

Professor Mannermaa in fact was not advancing Osiander’s ideas. But his interpretation of Luther’s understanding of justification by faith came, in my opinion, perilously close by positing that the righteousness of the believer is a “real-ontic” righteousness infused by theosis, the “divinization” of the believer by the Holy Spirit through trust in Christ. Mannermaa had come to his conclusion on the basis of what I regarded as too few Luther texts as he was dialoguing with theologians of the Russian Orthodox church. In the 1980s Lutheran theologians from Finland, during the Cold War a “neutral” country and next door to its former imperial master, Russia, had easier access to such conversations than did most Lutherans. Mannermaa strove to reach across confessional lines to bring Luther’s text and his message to those behind the Iron Curtain.

Mannermaa and I met a few years later at a conference in Eisenach, under the shadow of the Wartburg. The theologian with whom I disagreed became Tuomo, a brother who shared my passion for digging into Luther’s thought and my conviction that Luther’s voice deserves to be heard across confessional boundaries since the Wittenberg professor conceived of his message as a word for the whole church. We disagreed, but we recognized the common commitments and concerns that framed our differing readings of Luther. When his colleague Simo Heininen at the University of Helsinki invited me to lecture there, Tuomo and I had further opportunity to trade ideas. Our differences did not diminish, but my respect for his quiet faith in Christ and his burning concern for the unity of his church and for the cultivation of a strong faith and life of new obedience in Christ’s footsteps deepened at that time and in later encounters. It was clear that the love of the Lord Jesus had shaped this gracious, kindly, pious man.

At a time when Luther studies had drifted into doldrums of a sort, Mannermaa’s arguing that the heart of the Wittenberg theology lay in Luther’s adherence to theosis as an explanation of how God bestows righteousness upon sinners aroused discussion and returned researchers to the central question of the Reformation. The discussion around his ideas has moved beyond his initial ideas, but the stimulus he has given has served the church and scholarship in special ways. We thank the Lord for this friend.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.