First preached in the chapel of St. Timothy and St. Titus in 2009.

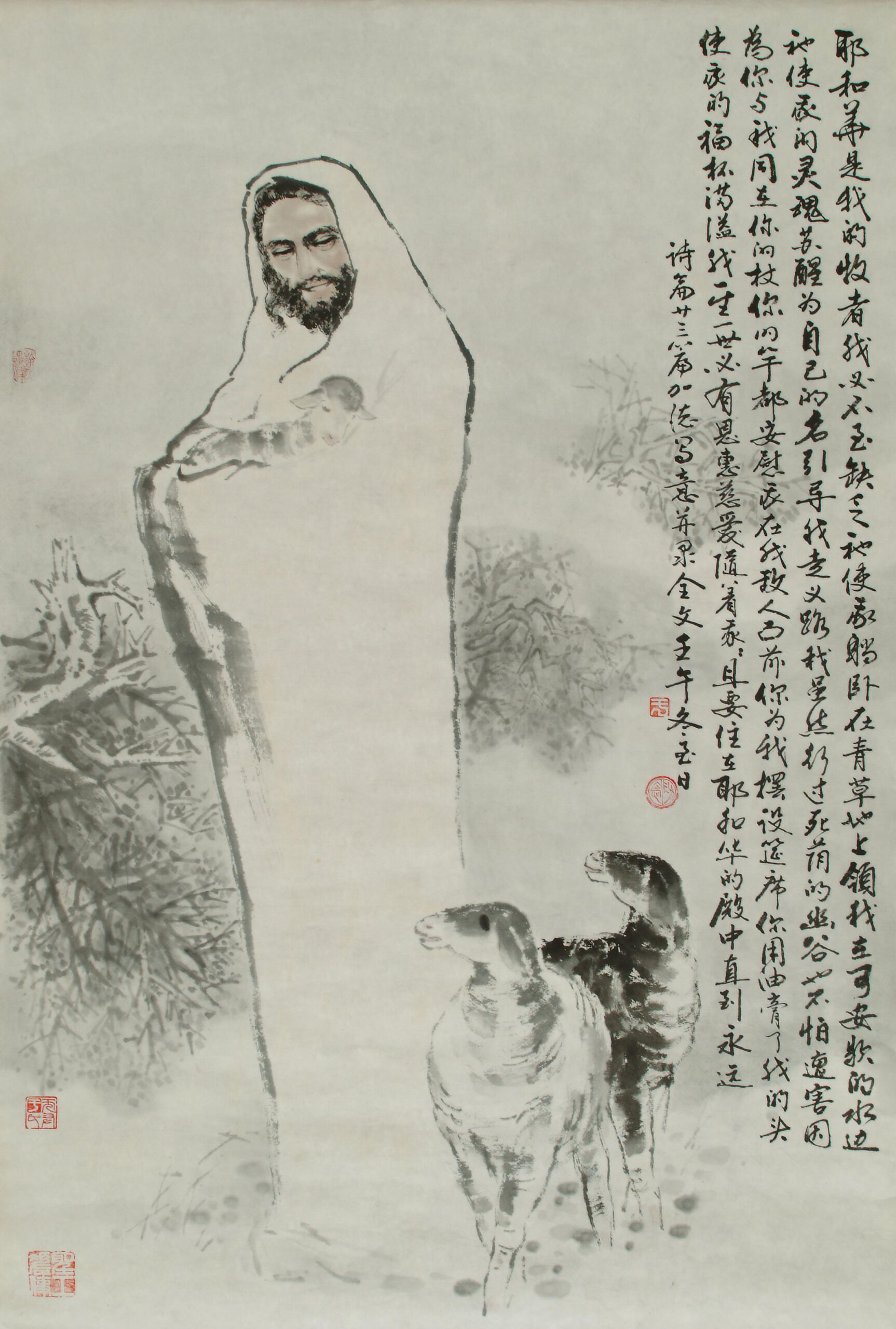

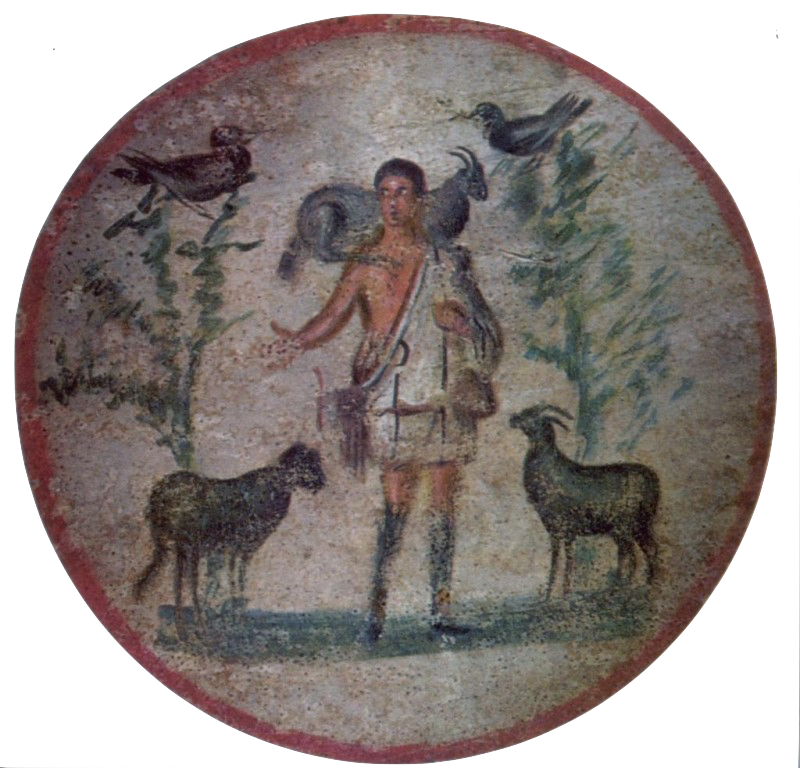

John 10 … the Good Shepherd. This is the sort of text that really speaks for itself. It offers such a vivid and familiar image that one hardly needs to expound on it or explain it. Jesus the Good Shepherd seems to be relevant in every age—from the ancient Christian catacombs where he was painted as a youthful Apollonian shepherd on walls and tomb inscriptions, to the modern Sunday school pictures of the gentle Jesus cradling a lamb. The Good Shepherd continues to be the most common and beloved images of the Savior. And this appeal and connection is there regardless of one’s knowledge and experience with sheep, the pasture, or the pastoral life. Of course, there are plenty of resources out there that can give you the first century context of the shepherd—and much of it is pretty helpful. But in the end, even without this kind of commentary, we “get it.” Christ the good shepherd does not leave us scratching our heads, instead, we find the image full of consolation and hope.

John 10 … the Good Shepherd. This is the sort of text that really speaks for itself. It offers such a vivid and familiar image that one hardly needs to expound on it or explain it. Jesus the Good Shepherd seems to be relevant in every age—from the ancient Christian catacombs where he was painted as a youthful Apollonian shepherd on walls and tomb inscriptions, to the modern Sunday school pictures of the gentle Jesus cradling a lamb. The Good Shepherd continues to be the most common and beloved images of the Savior. And this appeal and connection is there regardless of one’s knowledge and experience with sheep, the pasture, or the pastoral life. Of course, there are plenty of resources out there that can give you the first century context of the shepherd—and much of it is pretty helpful. But in the end, even without this kind of commentary, we “get it.” Christ the good shepherd does not leave us scratching our heads, instead, we find the image full of consolation and hope.

Perhaps this is because Jesus takes the shepherd and transforms this image into really something new and remarkable. Remember, the Good Shepherd’s definitive characteristic is that he “lays down his life for the sheep (John 10:11).” With these striking words, we have clearly entered into something unique and profound. No longer do we really dwell on pastoral images. When Christ says that the sheep hear the voice of the shepherd and know him by his voice, I suppose one could find analogies in the world of shepherds and sheep, but our affections are drawn into something far more human, far more intimate. The kind of intimacy found between the likes of mother and child. My own experience with my children has always reflected this. I might have my toddler happily sitting on my knee—completely enthralled with my bowtie or some such thing, when suddenly he hears the voice of his mother and, naturally, all is lost! He is nothing but squirm and scramble, in order to follow the voice that continues to shower him with incomparable love.

The kind of intimacy found between the likes of mother and child. My own experience with my children has always reflected this. I might have my toddler happily sitting on my knee—completely enthralled with my bowtie or some such thing, when suddenly he hears the voice of his mother and, naturally, all is lost! He is nothing but squirm and scramble, in order to follow the voice that continues to shower him with incomparable love.

Still, those who first heard him, who first heard his voice—in first century Palestine where there were a lot of sheep and shepherds—remarkably, they did not understand him. “Jesus used this figure of speech with them, but they did not understand what he was saying to them (John 10:6).” And after he goes through it again—even more clearly—they simply conclude that he is stark raving mad or has a demon. Now I ask you, who could be confused or offended at the Good Shepherd?

But for Israel, in the context of its own history and Scriptures, the shepherd always symbolized something more than just a herdsman with his flocks. Throughout the Old Testament, the shepherd image is repeatedly applied to Israel’s rulers and kings. Moses was called out from being a shepherd to lead God’s people through the wilderness. Israel’s greatest of kings, David, began as a shepherd and his call and anointing explicitly extends his former vocation into his new one: “He chose David his servant and took him from the sheepfolds; from following the nursing ewes he brought him to shepherd Jacob his people” (Ps. 78:70-71). And when the kings and rulers of Israel preyed on the people like wolves rather than acting as shepherds, the Lord announced that “I myself will be the shepherd of my sheep” (Ezek 34:15). And so the image of the shepherd is a bellwether of eschatological expectation, of the Lord’s Day of salvation and judgment, of the day of the messianic King. Thus when Jesus claims to be the Good Shepherd, there is more than Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony going on in the heads of the people. There is the great hope for divine deliverance—the great Day of the Lord, the day of judgment and salvation.

But for Israel, in the context of its own history and Scriptures, the shepherd always symbolized something more than just a herdsman with his flocks. Throughout the Old Testament, the shepherd image is repeatedly applied to Israel’s rulers and kings. Moses was called out from being a shepherd to lead God’s people through the wilderness. Israel’s greatest of kings, David, began as a shepherd and his call and anointing explicitly extends his former vocation into his new one: “He chose David his servant and took him from the sheepfolds; from following the nursing ewes he brought him to shepherd Jacob his people” (Ps. 78:70-71). And when the kings and rulers of Israel preyed on the people like wolves rather than acting as shepherds, the Lord announced that “I myself will be the shepherd of my sheep” (Ezek 34:15). And so the image of the shepherd is a bellwether of eschatological expectation, of the Lord’s Day of salvation and judgment, of the day of the messianic King. Thus when Jesus claims to be the Good Shepherd, there is more than Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony going on in the heads of the people. There is the great hope for divine deliverance—the great Day of the Lord, the day of judgment and salvation.

But now even that image is transformed—the attempts to make Jesus king by force are refused (cf. John 6:15f.). Before Pilate, Jesus speaks of a kingdom not of this world (John 18:33f.). His throne and crown is … well, you know. This messianic shepherd-king “lays down his life for the sheep”—and the crook by which he gathers them … that “there will be one flock and one shepherd” (John 10:16) is decidedly cruciform: “when I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all people to myself (John 12:32).” A dead shepherd. A dead king. Not much consolation and hope in that.

But I wonder if even more troubling was that voice—the sheep hear the voice of the shepherd. Already before, the words of Jesus caused offense. He claimed that his words are not his own but are from the Father, and that they are filled with the Spirit and Life (John 6:63). At one point many of his disciples say to Jesus, “This is a hard saying. Who can listen to it?” A few listen, “Lord, to whom shall we go, you have the words of eternal life.” But now that voice … that voice which call the sheep by name … the voice of the shepherd that lays down his life … continues to beckon, continues to call, continues resound! What kind of voice is this that echoes beyond the grave, that continues to speak and move beyond death? No wonder they thought him mad!

It’s the voice that offends today as well. The voice of the Good Shepherd is an invasive voice. It’s a voice that dares to call us by name, even if it is more convenient to live in anonymity, dares to call us together to live as one flock even if such fellowship impinges on our individual rights and freedom. It‘s a voice that dares to forgive sins even when we are not particularly eager to confess them. It is a voice that even dares to enter—(and this is so central to everything we do here at the seminary)—this voice dares to enter, at times like these, into our mouths (this man of unclean lips); and the voice of the Good Shepherd continues to be heard. “Feed my lambs” he said, “take care of my sheep” (John 21:15f.).

It has become clear to me, why we contemplate this text after Easter and why those who first heard Jesus could not understand his words. His words are nonsensical, offensive, and filled with promises that cannot be kept, unless … unless they are spoken by the Resurrected One–the shepherd-king who lays down his life, so that he might take it up again.

I once had a professor who spoke about the incredible transformation that happens in Psalm 23 after the psalmist passes through the valley of the shadow of death. Before, it is the idyllic almost sentimental picture of the sheep and the shepherd. But then it gets serious. Then comes “the valley of the shadow of death.” And on the far side of death’s deep darkness, our vision is transformed into something even more profound—no longer sheep in the pasture, we now sit as royal sons and daughters at the table of the king dwelling in his house forever. See, it’s not really knowing a whole lot about sheep that makes us fall in love with the picture and promise of the Good Shepherd—it’s EASTER! And it’s Easter’s proclamation that fills our ears with his voice, his word, his promise: “My sheep hear my voice,” he says, “and I know them, and they follow me. I give them eternal life, and they will never perish, no one will snatch them out of my hand” (John 10:27-28).

I once had a professor who spoke about the incredible transformation that happens in Psalm 23 after the psalmist passes through the valley of the shadow of death. Before, it is the idyllic almost sentimental picture of the sheep and the shepherd. But then it gets serious. Then comes “the valley of the shadow of death.” And on the far side of death’s deep darkness, our vision is transformed into something even more profound—no longer sheep in the pasture, we now sit as royal sons and daughters at the table of the king dwelling in his house forever. See, it’s not really knowing a whole lot about sheep that makes us fall in love with the picture and promise of the Good Shepherd—it’s EASTER! And it’s Easter’s proclamation that fills our ears with his voice, his word, his promise: “My sheep hear my voice,” he says, “and I know them, and they follow me. I give them eternal life, and they will never perish, no one will snatch them out of my hand” (John 10:27-28).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.