Editors Note: This book review was first published as the Featured Review in the Summer edition of Concordia Journal, 2021, Vol 47, No. 3, pp. 71-73.

THE WEIRDEST PEOPLE IN THE WORLD: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous. By Joseph Henrich. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2020. 704 pages. Hardcover. $35.00.

Harvard professor Joseph Henrich’s book has a weird title to say the least. Actually, he has not said the least (and maybe, he would allow, not the last), but he certainly has said a lot about the topic, about “How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous.” This weighty book runs 700 pages (150 of which are notes and bibliography), with text packed with analysis on hosts of studies along with detailed explanations of just how Henrich thinks this phenomenon has come about. Charts and graphs abound along with statistics by the gross, all to make the case that being WEIRD did not erupt overnight or result from a few fortuitous coincidences. The title may sound like catchy marketing, but this is a formidable book and not a quick read.

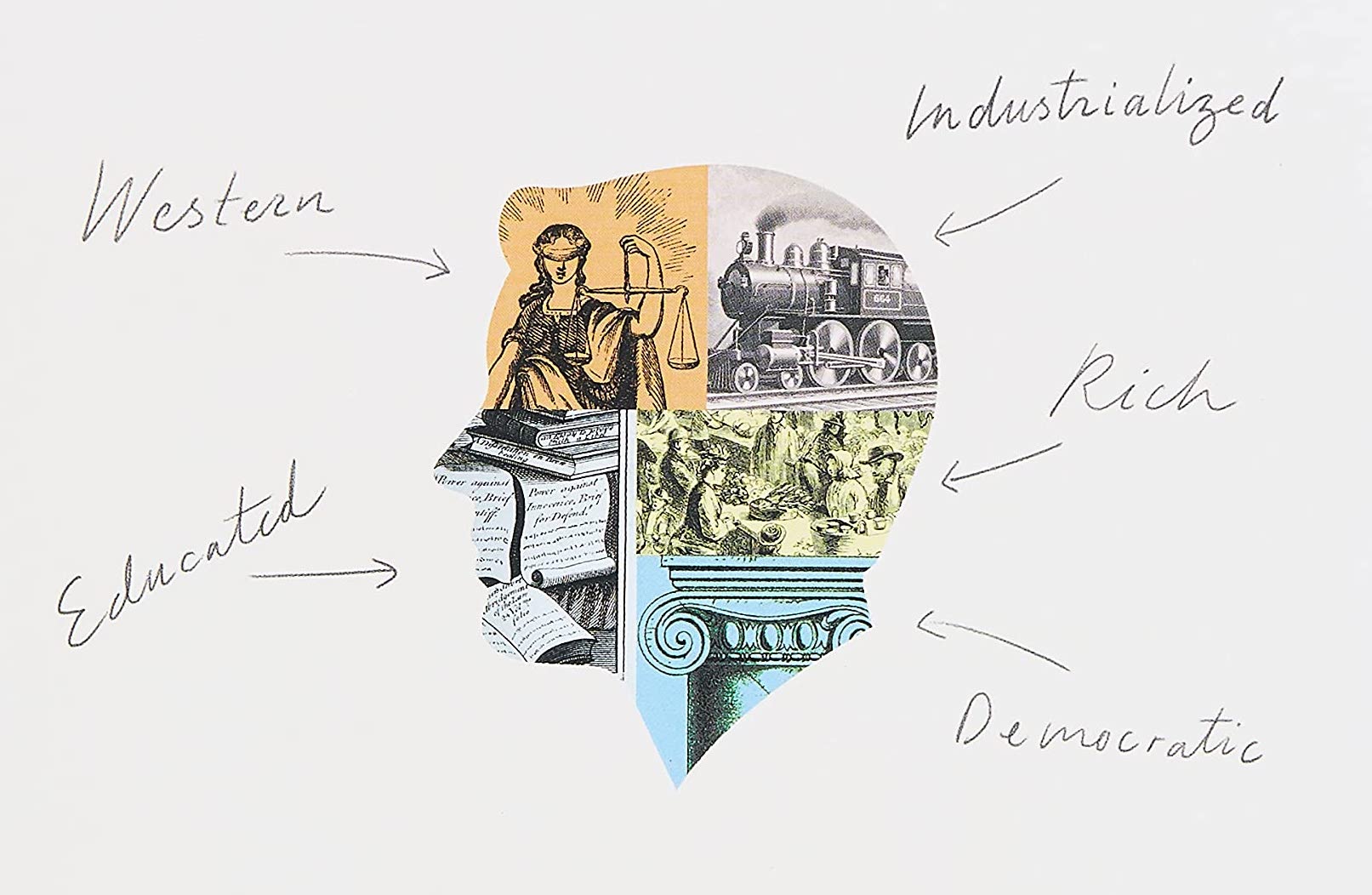

The WEIRD mind has been a long time coming, resting on long-term historical developments. Writing, for example, not only opened up communication possibilities, but actually rewired the natural brain, forging new paths for processing within those little gray cells. (And now the Internet along with other e-media are undoing and re-routing in different directions.) WEIRDness also rests heavily on the rise of Christianity’s efforts not simply to evangelize but also to socialize and enculturate, shaping habits and relationships of countless people groups, a task/opportunity the institutional church shouldered when the anchor of the Roman Empire gave way. So, for example, it now fell to church to adjudicate on ideas as simple as whom you could and could not marry, leading to family restructuring and undermining larger tribal connections where church-defined restrictions were no issue. Changes accumulated over centuries until eventually what emerged were people who were Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic—WEIRD.

To be sure, WEIRD people have not all marched lockstep, and those five traits show up in varying degrees. But compared to others not part of this long-term development path—the rest of the world—the difference is clear, provided one is open to looking and slow to jump to (self-serving) conclusions. And that is one of the problems Henrich highlights: WEIRD people come to see themselves as advanced (which in some ways they arguably are), but that often prompt them to look inward, self-referencing within their circle, a bit blind or dismissive of how others live. Values held fast by others can be missed or dismissed. The others, for example, display strong tribal traits with broad, complex family connections that prompt behavior different from a small, nuclear family (a Western household) built on different values. The others are moved by honor/ shame, careful of behavior that violates social custom within the intricate family. First and foremost, the tribe holds sway. In contrast an individual in a WEIRD context is first that: an individual oriented around keeping/ violating law (not family ways), kept on track due to duty/guilt. The others think holistically and more concretely, while the WEIRDest tend to be analytical and abstract, circumscribing issues with critical thinking. Those are just three of the big tendencies. Henrich has many more.

From late antiquity through the Middle Ages changes snowballed in the West. For example, states gradually developed, using laws promulgated to give them the upper hand over tribes whose customs were eclipsed as they were drawn into the alternative model. Church sometimes reworked folk beliefs or accommodated them for a time until more teaching could take place. That was done often through doctrinally oriented ritual, which at the same time built up church authority to bring still more changes. The others also had ritual, but it was more emotional and geared to a life enmeshed in nature. That living in and with nature gave way to science dissecting nature in an effort to understand, if not control. The WEIRD world can still be awe-inspiring, but it is no longer mysterious, just unknown for the moment, waiting to be explored. Some of these long-term changes (and more) were intentional. Others were unplanned responses to social and cultural challenges along the way. In any case, over a long history they created a different mindset, a foundational psychology that, in turn, set a new path socio-economically and culturally.

Those are but a few of many connected observations and arguments made to support the rise of the WEIRD and explain the effect it has had and still wields. Those hardly scratch the surface. And despite plenty of “yes, but” and “I’m not so sure” reactions to both the questions, evidence, and conclusions drawn, in general it is hard to argue that there is not a segment of the global population that thinks this way and got there somehow. And while this is not a theology book, for some in those circles to take a pass on Henrich is to ignore the context in which they work. Years ago, Peter Berger made plain that church also plays a larger role beyond the message, stretching like a sacred canopy to link history and cultural anthropology. When it comes to church, Henrich doubles down on that perspective.

It is a dense book! That unfortunately may be a drawback. A reader needs patience for all the detail. But shame on those who would dismiss Henrich out of hand. This is no backhanded woke mea culpa for the WEIRD having grabbed control, defined the agenda, and elbowed others aside. It is simply Henrich’s take on the world into which he and most of his readers were born. We cannot undo a legacy, but we can face up to present circumstances and challenges. Worse would be to fail to ask if his analysis is in any way true and what are we prepared to do about it. It is too easy to assume unthinkingly that WEIRD is just how everyone is (or ought to be). That is on display every day all around.

What does that say for church? The church, in Henrich’s analysis, played a large role in developing the WEIRD profile, particularly, again, in late antiquity and medieval times. But then interestingly from within came critical voices—Luther, for example—who both contributed to the continued/growing WEIRD model while also challenging a role church had established and was not keen on relinquishing. That ought to prompt church to think: things were not always thus and there is no guarantee things will automatically remain so (or as some want them to be). Was there not church earlier, and is there not church elsewhere outside a western (WEIRD) model? But when people live simply in the specious present, models can settle in and act as if it always were and ever should be the case. WEIRDness is a double-edged challenge: it developed and then rested on abstract, analytical thinking, and yet it too easily fails to use that critical thinking when confronted with a mirror, preferring instead to circle the wagons, acting just as tribal as the outside tribes themselves.

That happens not just to church, of course. Other historical institutions and voices prefer to settle in. But those also combine to accelerate into the modern world, developing what Henrich calls escape velocity that finally leaves the old behind. He is not keen on the individual hero in history, but their challenges do accumulate. How different are things? An equidistant look before and after the Enlightenment shows how far things have come, but also the line between WEIRD and the other is not as distinct as before. Still, the risk of WEIRD blindness exists. Henrich’s book helps sort things out. Readers may not all be convinced (although first there is a lot of evidence to be grappled with honestly), but it is hard to deny that there is something WEIRD going on.

Robert Rosin

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.