Editor’s note: In the Fall 2022, Volume 48 (pp 55-66) issue of the Concordia Journal, Dr. David Peter provides an Anatomy of a Sermon by Rev Brian King. The sermon was preached at Webster Gardens Lutheran Church in Webster Groves, Missouri, on July 10, 2022. It is represented in italic type which can be read all at once by following the gray bars.

Everyone loves a story. For this reason, most people are pleased to hear sermons that are based on parable texts from the gospels. Indeed, many pastors enjoy preaching on these short stories that originated from Jesus’s lips. Yet it doesn’t take long for a thoughtful preacher to discover how challenging it is to preach on parables. Thomas Long comments: “Preaching on a parable is a novice preacher’s dream but often an experienced preacher’s nightmare. Preaching the meaning of a parable with competence and integrity is more demanding than initial appearances.”1

It can be challenging to preach on parable texts because of the difficulties in interpreting them and in communicating their intended meaning. In this sermon Pastor Brian King demonstrates how both outcomes can be achieved in a way that engages a contemporary audience. He expounds Jesus’s parable of the “Rich Fool” from Luke 12:13–21. This was one of a series of sermons based on parables in Luke’s Gospel (chapters 10 through 18). In this sermon Pastor King attends to both the narrative in the parable and the narrative of the context in which the story was told (what he calls the “backstory”) in order to communicate the message of the text and to proclaim law and gospel to the hearers.

We value families around here. I hope that’s something that you know. Family time together is important, time to bond. Families do that in different ways. Maybe your family does puzzles. Or you play cards. Lots of families play board games. [Display board game boxes] Anybody play Candyland? Maybe classics like Chutes and Ladders? Not all board games are created equal or bring people together in the same sense of caring and lightheartedness. Like “Sorry”—(the sarcasm is built right into the title!) But no game threatens to tear apart the fabric of the family like . . . Monopoly. Does anybody play this? Do you still speak to each other? Monopoly was designed to tear families apart. It’s cutthroat! You play this game, and your 9-year-old immediately transforms into a cigar-chomping tycoon.

The introduction to this sermon accomplishes four ends. First, it affirms a prominent value of the congregation—upholding the family (Brian King is the pastor of family life at this church). Second, it introduces the major image that will unite the sermon—the game of Monopoly. Third, it connects with the hearers by relating to their shared experiences of playing board games. Fourth, and most importantly, it unites these foci to describe how family members who play the game often end up at enmity with one another. This in turn will open the hearers to relate to the setting of the biblical text—the enmity between brothers over money.

The introduction to this sermon accomplishes four ends. First, it affirms a prominent value of the congregation—upholding the family (Brian King is the pastor of family life at this church). Second, it introduces the major image that will unite the sermon—the game of Monopoly. Third, it connects with the hearers by relating to their shared experiences of playing board games. Fourth, and most importantly, it unites these foci to describe how family members who play the game often end up at enmity with one another. This in turn will open the hearers to relate to the setting of the biblical text—the enmity between brothers over money.

The statement that “no game threatens to tear apart the fabric of the family like Monopoly” sets the stage for the scene in the biblical text about a brother who is enraged about his share of the inheritance. But before that scene is expounded, the preacher develops the major image of the Monopoly game, describing the dynamics of the board game that will move forward the sermon’s theme.

And we not only own Monopoly, we have “Catopoly,” “Monopoly: Animal Crossing Edition.” You can dress it up however you want, it still doesn’t change the fact that someone’s gonna walk away with everything, all their own properties, and everyone else’s properties, and houses and hotels piled up in front of them, with all the colorful money. And everyone else is going DOWN! Slowly and painfully. And it doesn’t matter what your house rules are—(“free parking gets the community chest pot!”), one person leaves happy and everyone else is in a rage.

Here Pastor King develops the master image or metaphor for the sermon, that of playing the game of Monopoly. He refers to various versions of the board game, and he describes the outcomes of playing the game—the winner takes all the wealth while the losers are resentful. He purposefully selects and manages aspects of the image— the details about playing the game—in order to relate these to the opening situation in the Lucan text.

The master image of Monopoly will support the central theme and movement of the entire sermon. Prominent scholars in homiletics affirm the value of using such an overarching metaphor. Paul Scott Wilson calls this the dominant image by which listeners see the same image in a sermon introduction, on one or two other pages, and in the conclusion.2 Peter Jonker labels this rhetorical devise the controlling image, defining it as an “evocative picture or scene that shows up repeatedly in a sermon and communicates either the trouble or the grace of a sermon theme, therefore helping to accomplish the sermon’s goal.”3 The dominant or controlling image appears not only in one section of the sermon, it pervades the sermon as a whole. It directs how the entire sermon will be visualized and understood.

If you’ve played Monopoly, maybe you’ve felt like this guy who kicks off Jesus’s parable. He didn’t just come from a brutal round of playing Monopoly, he’s enraged with his family about a real conflict over money. He comes to Jesus (Jesus is actually right in the middle of teaching) and says, “Teacher, tell my brother to divide what our father left us!”

We don’t know all the details, but it’s clear he feels like he’s on the losing end of the game.

Jesus pivots his teaching. First, he’s like, “Who elected me judge of this case? I didn’t know I was up for the position!” And then proceeds to tell a story you just heard, often referred to as the “Parable of the Rich Fool.”

At this point Pastor King uses the image of Monopoly to move to the biblical text and its opening scene. This is what he will later call the “backstory” to the parable. This backstory is the dialogue between Jesus and the man who complains about his brother, the context in which Jesus tells the parable. Understanding that context is critical to apprehend the meaning and application of this parable.

When such a historical or literary context—the “backstory”—is provided by the biblical author, the preacher will want to examine it for the sake of interpreting the parable. This may involve, as in this case, a mere retelling of the context before narrating the parable. This approach reserves explanation of the context’s significance to a later point in the sermon. Another option is to more thoroughly expound the implications of the “backstory” before embarking on the parable itself. In any case, this contextual material should not be neglected. It is key to understanding the parable.

But rather than losing, Jesus’s story is about a guy who’s winning. “There was once a rich man who had land which bore good crops.”

It’s more than he expected! It’s like he’s watching his properties and hotels pile up in front of him; it’s exciting!

Now, in this story, Jesus is not saying this was a bad man. No evidence that he swindled people out of what was theirs, nothing that says that he was trying to sneak hotels onto Park Place AND Boardwalk while nobody was looking.

But he has some flaws. He’s the only character in this story, but there’s a conflict.

The rich man uses the wrong pronouns. (How current does that sound?) People argue about the place and purpose of personal pronouns, but look at this rich man:

Let’s put his inner monologue up on the screen.

Looking at the screen or in your Bible, count up the times he uses the pronouns “I/ME/MY.”

‘I don’t have a place to keep all my crops. What can I do? This is what I will do, I will tear down my barns and build bigger ones, where I will store the grain and all my other goods. Then I will say to myself, Lucky man! You have all the good things you need for many years. Take life easy, eat, drink, and enjoy yourself!’

He uses the pronouns “I/ME/MY” at least ten times! Even more if you count the “you’s” where he’s talking to himself.

He wants more room and more stuff and more convenience. He did not look at his possessions as ways to bless others.

And so, in this short, three-act story, the man comes into great wealth, he makes plans to keep it safe all to himself, and then God shows up and says, “You’re dead!” (That show isn’t going to have a season two. He’s DONE!)

The typical parables of Jesus are “short past-time narratives in form. 4 That is certainly the case with this parable. Because it is a narrative, it consists of both character and plot. In retelling and expounding the parable, the preacher can examine its characters or its plot, or both.

Here Pastor King minimally engages the plot, assuming that the hearers are adequately familiar with it. He summarizes the plot succinctly in one sentence as a “three-act story.” What he primarily develops is the character of the rich man. He clarifies that the rich man is not technically corrupt, but the preacher articulates the character’s flaws by analyzing his inner thoughts. Pastor King diagnoses the character’s selfish and sinful orientation.

It is uncommon for biblical narratives to do extensive character development. This is especially true of short parables. But contemporary audiences resonate toward character development; it helps them identify with the characters and enter into the story. This is why it is frequently advantageous in preaching parables to elaborate on Homiletical Helps 61 and even expand the description and analysis of main characters in the story. Notice also how this section of the sermon alludes to the master image of the Monopoly game in the retelling of the parable’s narrative when it states, “he’s watching his properties and hotels pile up in front of him,” and as it refers to sneaking hotels onto Park Place and Boardwalk.

So what’s this about?

One layer of this story IS a warning against greed. Jesus said, “watch out for it, it’s sneaky!”

However, Jesus’s point doesn’t seem to be that ownership is evil, or you should sell everything that you have. In other parts of God’s word there are several encouragements to save for the future.

But by contrasting this man’s untimely death with all the stuff he’s not going to be able to enjoy for himself, one thing Jesus IS conveying is that these things are less important than you think.

There’s a profound wisdom in Jesus’s prayer “Give us this day our daily bread . . .” My daily bread is less likely to balloon into a god.

And so, Paul instructs his friend Timothy, a young pastor, with these words: “Command those who are rich in this present world not to be arrogant nor to put their hope in wealth, which is so uncertain, but to put their hope in God, who richly provides us with everything for our enjoyment” (1 Timothy 6:17).

The rich man mistook the uncertain for the certain.

That’s instructive, for your bank account, stock portfolio, and hobbies you spend your money on.

Pastor King signals the focus of this parable by asking, “What’s this about?” This also signals the approach to preaching this parable that he will take. The approach is to isolate and identify a specific truth or teaching for reflection and application. This is called “preaching the teaching” of the parable. This approach involves identifying the teaching that Jesus intends to communicate and then developing that teaching by clarifying, explaining, analyzing, applying, or proving it.

Such an approach to this parable is particularly appropriate because it does not have a deeper (allegorical) level of meaning to it that is typical of many parables. This parable is more of a teaching story in which the application is on the surface rather than at a sublevel. God explicitly addresses the rich man as a fool for his misplaced priorities (v. 20). In its literary context Jesus warns against greed and expressly devalues the abundance of possessions (v. 15). Finally, Jesus appends a moral to the story by condemning the one who values earthly riches over the riches of God (v. 21).

Accordingly, Pastor King identifies the initial teaching as a warning against greed. Then he homes in more specifically on misplaced values. He proceeds to relate this to idolatry (“balloon into a god”) and our source of security. The parable is used to communicate an important teaching about priorities in our lives—the folly of valuing material wealth over God.

Having articulated this teaching, Pastor King then uses it to proclaim the accusing law to his hearers. He warns against sin by quoting the Apostle Paul’s exhortation not to put hope in wealth and by directing the hearers to reflect on how they view their own finances and possessions.

But it’s not all we walk away with. Remember from last week, that a parable is not a delivery system for an idea, but a house where the listener is invited to take up residence.

So more than just a lesson on how I view and manage my possessions, Jesus invites us into this narrative house that he’s built. And when we do that, we actually see Jesus emerging from his own story.

In this brief section the preacher highlights a distinctive quality of the genre of parable. A parable does not merely communicate a concept; it evokes an experience. This evocative quality of story is imagined as entering into a house for the hearers to reside in. The approach of inhabiting the parable was explained more thoroughly during the previous sermon in the series, and so is only briefly mentioned here. Nonetheless, it demonstrates that the preacher acknowledges and engages one of the distinctive qualities of the literary type we call a parable—its evocative nature.

Most significantly, Rev. King uses this quality to proclaim the gospel by moving to a deeper reflection on Jesus. He states, essentially, that as we inhabit the parable more reflectively, we encounter Christ more thoroughly.

It’s kind of like when you’ve seen pictures like this where there’s lines or patterns, and it’s when you look at the negative space, you see the real meaning. [This image is shown on the screen:]

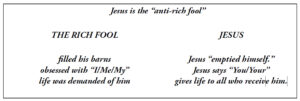

In this story, look for Jesus in the negative space, because Jesus is the “anti-rich fool.” You see him in the contrasts. [The following slide is projected:]

The rich man filled his barns (or at least he planned to). “Gotta keep this stuff safe, ready for me when I need it!”

Well, what’s Jesus like? Paul writes to the Philippians—he has divine identity, everything is his. Barns filled to the top! And “he made himself nothing” (Phil 2:7). The literal word, ekenosen, Jesus “emptied himself.” What do you need? A right relationship with God. A certain identity. True belonging. That’s in Jesus’s barn. It’s yours. What a contrast.

Remember the rich fool’s pronouns? The rich fool is obsessed with “I/Me/ My” “What will I eat what will I drink, how will I have a good time?”

Jesus says, “You/Your.” “This is the blood of the covenant, shed for YOU for the forgiveness of YOUR sins . . .”

The rich fool placed his hope, his identity in everything uncertain, and his life was demanded of him.

Jesus, through his generosity, takes on your sins, your greed, your selfishness. He gives life to all who receive him.

The house rule for us to understand today is that in OUR house, we place our focus on Jesus, the One who emptied himself for us.

This is the first section of gospel proclamation. The pericope of Luke 12:13–21 contains no explicit gospel content, no promise of divine mercy or forgiveness. Jesus’s teaching convicts and condemns, not comforts. Nevertheless, Pastor King undertakes to use this law-laden text to deliver the gospel message.

He does so in a creative manner, by way of contrasting Jesus from the rich man (“You see him in the contrasts”). One way to proclaim the gospel from a text that contains only law is to contrast Jesus from the sin or sinner in the text and then to present Christ as the one who fulfills what sinners lack. Here the preacher transitions to this approach using the dynamic of negative space that is illustrated in the projected image of the name JESUS. He then highlights three characteristics of the rich man that are drawn from the parable, and he demonstrates the opposite Jesus is the “anti-rich fool” THE RICH FOOL JESUS filled his barns obsessed with “I/Me/My” life was demanded of him Jesus “emptied himself.” Jesus says “You/Your” gives life to all who receive him. characteristics in Jesus. By articulating these characteristics of Christ, Pastor King is able to proclaim Jesus’s self-sacrificial work that forgives sin and gives life. He directs the hearers to focus on the gracious characteristics and actions of Jesus that are revealed outside of the parable in a way that arises from the content inside the parable, thus delivering the gospel.

This concludes the first cycle of law-gospel proclamation. But there is more. A second cycle commences with a more direct application of the law to the hearers.

You know, maybe you have a hard time seeing yourself as the Rich Fool. He’s such a caricature of the cigar-chomping Monopoly tycoon.

But you know who you and I are? The guy who asks Jesus about the inheritance. He’s the really interesting one.

Remember from last week that backstory is important? Let’s look at what was going on: We saw that there are these thousands gathered, squeezed in, stepping on each other to hear. What was Jesus teaching about?

Jesus was sharing about the power of God who has authority even over heaven and hell. But also assuring them that this same God knows every hair on their head. He promises them that the Holy Spirit himself will guide them when they’re persecuted.

This man hears all this; we know because he’s close enough to ask Jesus a question. And he blurts out “tell my brother to divide what our father left us!” He missed it.

This reminds me of a character is a classic book called Pilgrim’s Progress, written in the 1600s so it’s a challenging read. But it’s an allegory of the Christian faith. And in one section of the book, we’re introduced to this character who’s described as a “man with a muck rake.”

[The painting of a man with a muck rake is shown on the screen.]

He has a rake. All day long he’s bent over. Raking up mud and sticks. Someone stands above him and offers to trade him his rake for a “celestial crown.” You know what happens? He never looks up. And he ignores the offer. He’s chosen what’s important to him.

All this certain, eternal, heavenly truth is offered from God who has all authority, who also treasures you over many sparrows. And this guy is obsessed with “I didn’t get my fair share!”

Earlier in the first cycle of law proclamation, Pastor King directed his hearers to identify with the character in the parable, the rich fool. But now he directs them to identify with the original person whose grievance prompted Jesus to tell the story. He associates the hearers with the character in the “backstory,” the man who demanded that Jesus arbitrate his financial issues.

This is a clever rhetorical turn. The preacher now develops the setting of the backstory to develop his convicting message. The man introduced in verse 13 had been in the audience hearing Jesus’s message of God’s gracious power and promise, yet he missed it all to be consumed with mundane bitterness. So also, we often miss the grace of God to be focused on self-serving grievances. Pastor King holds up the mirror of the law so that sinners see themselves reflected in both the rich fool and the bitter brother, whose sin is further developed using the illustration of the muckraker. Thus, for a second time the preacher reveals sin, setting the scene to call the hearers to repent.

In our house, we’re honest before God, we don’t try to look better than we are. I

n our house, we place our focus on Jesus, the One who emptied himself for us.

We confess that we are like the rich fool, like the muckraker. Would you pray with me to confess our sins? Let’s use the words on the screen.

[Slide projected]

Lord, I allow greed and selfishness to block my view of your generosity. I ignore your offer of true life, focusing only on what’s in front of me. I’ve exalted worries about my future to first place in my life. Forgive me for the sake of Jesus, who emptied himself for me.

You and I are not rich toward God all the time. But Jesus, who emptied himself for you, is rich toward you every time. He became nothing for you. He emptied himself for you. He forgives you of your greed and selfishness and every other sin. He gives you the riches of his righteousness.

He takes the rake out of your hand. He loosens your grip on those uncertain things so you can grasp what’s certain! He gives you something certain that you can be confident in, that you belong to him, that you are important and valuable to him.

You’re forgiven.

You’re rich toward God. That’s your identity in him!

In Jesus’s name, Amen.

In this concluding section of the sermon Pastor King explicitly calls for a response from his hearers. It is a salutary practice to conclude one’s sermon by calling the hearers to respond according to the goal of the sermon, in this case to trust in Jesus rather than riches (faith goal).

But the intended response is also one of repentance over the sin they have just been convicted of, and they are given the opportunity to express that contrition by speaking words of confession. Typically, the Confession and Absolution are located at the beginning of the service immediately following the invocation (there are good reasons for this). But on occasion it is appropriate and meaningful to close a sermon with words of confession of sin and forgiveness that articulate the law-gospel message of the sermon. Pastor King demonstrates that kerygmatic strategy here.

Most importantly, the delivery of the word of absolution brings evangelical closure to the sermon. The words of forgiveness complete the second cycle of lawgospel proclamation. The first cycle of gospel proclamation focused on the grounds of forgiveness and life—Jesus’s emptying of himself to give righteousness. This final cycle of gospel proclamation more directly applies the gospel promises to the hearers, delivering the gifts of forgiveness and a new identity in Christ. The evangelical promise sends the hearers forth forgiven and fortified to focus on Jesus and their identity in him.

To summarize this analysis, Pastor King’s sermon based on the “Parable of the Rich Fool” from Luke 12:13–21 demonstrates the following qualities:

It employs a dominant image (the Monopoly game) to introduce the theme of the sermon and unify that theme throughout.

It engages the content of the parable—its plot and characters—but also understands its meaning in view of the literary context (the “backstory”).

It develops the homiletical focus on a lesson to be taught (preaching the teaching of the parable) which is a warning against greed and misplaced priorities.

It proclaims the gospel from a text that contains only law by using the strategy of contrast.

It proclaims law and gospel twice by cycling through two iterations of proclamation, each with a distinctive approach to convict and comfort the hearers.

It guides the hearers to respond to the message of the parable with repentance using words of confession followed by the announcement of forgiveness.

All of this is accomplished with creativity and in a conversational style that invites the hearers to inhabit the experience of Jesus’s parable.

Endnotes

1 Thomas Long, Preaching and the Literary Forms of the Bible (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1989), 87.

2 Paul Scott Wilson, The Four Pages of the Sermon: A Guide to Biblical Preaching (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1999), 51.

3 Peter Jonker, Preaching in Pictures: Using Images for Sermons that Connect (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2015), 4.

4 Jeff Gibbs, Matthew 11:2–20:34 Concordia Commentary (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2010) 664.

Dr. David Peter

Professor of Practical Theology

Concordia Theology, Saint Louis

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.