Over the last decade the church has been challenged repeatedly regarding its Scriptures: Is the Bible legit? Or were there multiple “Bibles” with multiple messages? Can we now in our enlightened age throw off the shackles of ancient “superstition” and “recover” an ancient source of meaning that is more appropriate? The Davinci Code book and movie first brought this to popular attention. This was followed by the Gospel of Judas “discovery” and other smaller items over the last several years: “Gabriel’s Vision,” the “Jesus Family Tomb,” the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife,” etc.

Over the last decade the church has been challenged repeatedly regarding its Scriptures: Is the Bible legit? Or were there multiple “Bibles” with multiple messages? Can we now in our enlightened age throw off the shackles of ancient “superstition” and “recover” an ancient source of meaning that is more appropriate? The Davinci Code book and movie first brought this to popular attention. This was followed by the Gospel of Judas “discovery” and other smaller items over the last several years: “Gabriel’s Vision,” the “Jesus Family Tomb,” the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife,” etc.

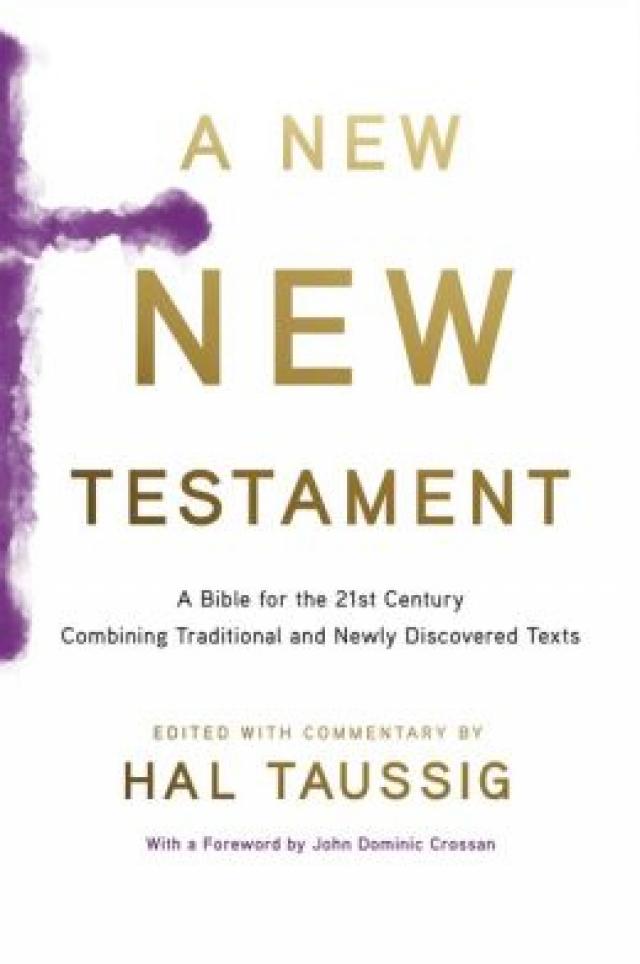

On Christmas Eve, Joe Nocera published an op-ed piece in the New York Times that popularizes another example of this trend. Earlier this year, Hal Taussig, professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York, published A New New Testament: A Bible for the 21st Century Combining Traditional and Newly Discovered Texts. Taussig is also co-pastor of the Chestnut Hill United Church in Philadelphia, and his preaching reflects his goal of using a newly-constructed “New Testament” to teach and preach from–to create a “theology” that is more in line with the thinking of our age, which can no longer tolerate the scandal of a virgin birth, a crucified Messiah, or a resurrection from the dead.

Many print and media outlets continue to hammer away at the Scriptures and the Gospel. And they do so in a way that we pastors have, perhaps, not prepared our people to deal with. We have perhaps avoided helping them to see the Scriptures as God’s Word, given by the Spirit in and through the Church. We fall back on easy formulas—which are not wrong, but do not do a very good job of dealing with this anti-Christian rhetoric as it hits their TV and internet screens.

So how should we prepare our people so that their trust in the certainty of the Scriptures and its message is not shaken by the “New New Testament” and other challenges? There is much that can be done, and at the end of this brief note I have provided links to additional resources. Here I will interact specifically with the claims made by Nocera and Taussing in the New York Times piece, and demonstrate the typical half-truth (or half-understood) way of speaking that careful historical and theological work can help expose.

Nocera writes:

One point Taussig and other academics make is that we really have no idea why certain books are in the New Testament and others are not. “The making of the New Testament took 500 years,” Taussig told me, who also notes that we have no idea, in fact, who wrote many of the books that make up the New Testament — or the early Christian texts. What is almost surely true is that they were not written by Luke or Mark — or Mary Magdalene, for that matter. Even the earliest of them was written decades, if not centuries, after Jesus’s life.

This argumentation represents typical half-truth academic-speak. A couple examples:

“We really have no idea why certain books are in the New Testament and others are not”

This is correct in the sense that we have no church council records or official statement from an ecclesiastical figure, that declares certain books authoritative and others not—at least not until the 4th century, far later than the first and second centuries, the period under debate. However, we have two historical sets of evidence that confirm that the New Testament writings were regarded as authoritative and inspired while other writings (like the Gospel of Mary) were not.

The first set of evidence is the physical, historical documents—the manuscripts themselves—that consistently reproduce and pass down a core of writings: The Four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John) and the thirteen Pauline epistles. Manuscripts discovered in the last 75 years date back as early as the late second century, all uniquely testifying to this core of New Testament writings—and no others.

A second set of evidence is the use of these writings by early teachers. Already by the end of the first century, a pastor in Rome named Clement wrote a letter in which he references most of the letters of Paul. By the mid-second century, pastors like Irenaeus in Lyon (about 180), Clement in Alexandria (also about 180), and Justin in Rome (about 160) were all teaching from and referencing specifically Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. All three uses the same phrase about these writings: they were “handed down to us,” meaning that the collection of the four Gospels was not their creation, but that it pre-dated them. Furthermore, notice that these teachers come from distant corners of the Roman Empire–indicating that the Four Gospel collection was wide-spread throughout the early church and not unique to any single location.

Returning to the statement that “we have not idea why certain books are in the New Testament and others are not,” we really don’t need to know why they were gathered together and considered inspired and authoritative. It is a fallacy to assume that if we do not know precisely the reasons for bringing them together, then we must doubt their authenticity and authority. But we do know, based on sound historical research, the fact of their early, consistent, and wide-spread use, and that they were universally used as Scripture by the church in the early-mid-second century.

“The making of the New Testament took 500 years”

Another partially-true, and in fact incorrect statement. As noted above, the core writings of the New Testament—the Gospels according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John and the Letters of Paul—were never in dispute by anyone at any time. There is not a single record of anyone claiming these writings to be false. The mid-second century end-point for this process is critical, for every so-called “Gospel” (Mary, Thomas, Judas, Philip) was written after the canonical Gospels were already universally considered authoritative. In fact, the Gospel of Judas, the Gospel of Mary, and the Gospel of Philip are universally considered to be derivative of and based on the canonical gospels. They take characters, and in some cases even wording, and twist and alter them to suit the needs of a later group of people who claimed—to a greater or lesser extent—a further revelation about “god” than what Jesus of Nazareth taught and embodied, and which was proclaimed by the apostles and the church.

Strikingly, authors like Taussig consistently fail to reference the Pauline Letters in these discussions. The divinity of Jesus Christ, his resurrection, justification and salvation by his work are all quite clearly taught. Even the most skeptical NT scholars acknowledge that letters like Romans, Galatians, 1 Corinthians, and Philippians date to the 50s of the first century—150 to 200 years prior to the writing of these non-canonical gospels. Any claim that the development of key teachings about God and his work in Christ are late developments falls away when one turns to the Pauline Epistles.

The statement, “The making of the New Testament took 500 years,” Nocera seems to be referring to the fact that some writings of what we now call the New Testament were not universally used by all Christians in the first several hundred years of the church’s teaching and preaching. Revelation, 2 Peter, Hebrews, James, and Jude were among the most uncertain; some orthodox teachers rejected some or all of them entirely. This is historical fact; however, careful readers will also note that these writings are among the last of the NT writings to be written, their authorship is uncertain, and, most importantly, they are among the writings that are the most difficult to interpret; the Gospel of Christ is not as clearly taught in these writings as in the “core” writings. This does not make them “wrong” in any sense, but it is the case that the early church did not hear the voice of the shepherd in these writing as clearly as it did in the core NT writings.

The church of the Reformation recognized this historical fact, and were careful to distinguish the firm and certain writings (called “homolegoumena) from the uncertain and disputed writings (called “antilegomena”). Luther himself considered Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation as the latter, and in his New Testament translation moved them to the end of the NT as something of an appendix to the other writings–he did not number these in his table of contents, as he did the other writings. Martin Chemnitz, the reformation theologian who thought the most carefully and explicitly about the doctrine of Scripture, listed even more books as secondary (he in fact called them “apocrypha” in his Enchiridion, a handbook for pastors): 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation.

Today still we are careful to center our teaching and preaching on the Gospels and Paul’s letters—virtually all sermons preached in Lutheran churches today will be based on those texts—though now we are able to read Revelation, James, and Hebrews, for example, with a clearer understanding of the historical settings and goals, and therefore able to hear the Gospel even in those writings.

So, “The making of the New Testament took 500 years” is a partially true statement. But what Taussig does not acknowledge is that writings like the Gospel of Mary, etc., are never copied in the same manuscripts as other NT writings; they are never quoted by the same people who used the NT writings; they are never the basis of sermons, practical, or theological treatises in the early church. The placing of these writings alongside the NT is modern phenomenon, something that started only in the last few decades. This move is only partially a historical move—history done poorly, I might add. Rather, as Americans continue to find the teachings and the salvific work of Jesus less and less palatable, scholars have used the canon (and for that matter, questions about the copying of manuscripts) to challenge historic creedal Christian faith and life. In other words, historical research is not calling the canon into question and causing us to re-evaluate divine truth. Rather, our society has rejected divine truth, and therefore looking for another source, a “justification” to set aside the Scriptures and find other writings that can be bent and fashioned to suit modern sensibilities.

“We have no idea, in fact, who wrote many of the books that make up the New Testament”

This comment is an oversimplification of more nuanced scholarly argumentation. To be specific, the names Luke and Mark (nor John or Matthew, for that matter) do not appear in the actual writings themselves. There is no author by-line in ancient literature such as modern literature has–in fact, “publishing” and copyright as we know it did not exist. Nevertheless, the earliest tradition, again in the manuscript copies themselves and in descriptions from the first centuries universally ascribe these writings to these four authors. Furthermore, if one wanted to use a fake name to give false authority to a writing, using “Luke” or “Mark” would hardly be good choices—“Peter” or “James,” for example, would have been much more effective. So there is no reason to question Luke or Mark as the authors of the writings. The Gospel of Judas and Gospel of Mary, on the other hand, written well over a century after the time of Jesus, can certainly not have been written by the those two figures; every scholar today will place them in the second century or later and acknowledge that they were not written by anyone who saw or know Jesus of Nazareth.

The Real Problem

The last few paragraphs of the NYTimes essay show the real problem with “adding” non-canonical writings to the New Testament. For this move is an attempt to make them authoritative, to serve as a basis for teaching and life. The essay concludes:

In his sermon about The Thanksgiving Prayer, Taussig used it to offer a meditation on the difficulties of both societal and personal growth. “There is a womb pregnant with divinity itself,” he said as he neared the end of his sermon, “making us ready for taking that next step forward, in the relationship that is hurting, the psyche that doesn’t know what to do, and the society that needs help.”

Scripture indeed.

Merry Christmas.

Is this hope? There is some vague “divinity” which is somehow active in us individually, which impels us, individually, to find some vague comfort in spite of the hurting and suffering in our lives and in the world. The message is one of “don’t worry, things will be okay, because there is an impersonal divine spark who gives us power to help ourselves.” This is the oldest religion ever–a religion of self-help, a religion of a deity whose job it is to make our lives “better.” In ancient times, this deity made the crops grow and guaranteed the rains and the harvest. In modern times this deity sounds a lot like Oprah Winfrey. You don’t need to “add book to the New Testament” to come up with teaching like this. Humans have been trying to live by religions like this for generations. And humans continue to fall into war, suffering, trampling on the weak and the motherless, and everything else that we have failed to fix by our own power. This is no “Christmas,” for there is no “Christ.”

But Scripture testifies to a different God, one who is not vague and remote, but one who is all-powerful yet ever-present. This God came into our world in the flesh as the Christ, a baby born in Bethlehem, and grew to demonstrate the reign of this God in power and awesome deeds as he healed, welcomed, and fed his people. Finally, this Christ sacrificed himself on a cross, and was raised from the dead to bring about the restoration of his people and all creation—no more “hurting,” no more “no knowing what to do,” no “society needing help” from people who are themselves helpless.

We don’t need a “New New Testament.” We need a Savior. Christ has come, Christ is risen, Christ will come again.

For more thorough discussion of these points, please see the following online resources:

“Which Jesus? How Many Gospels” video series, taught as a Lay Bible Institute at Concordia Seminary in 2006

“How We Got the Bible” DVD/video series, Lutheran Hour Ministries, 2009.

“The Bible on Trial: A Reasonable Doubt” DVD/video series, Lutheran Hour Ministries, 2011. I would especially encourage people to watch this one-hour video.

“Lost Books?” DVD/video series (featured speaker), Lutheran Hour Ministries, 2013.

A more academic piece, that deals with virtually every point raised by Taussig, is “Jesus and the Gnostic Gospels,” Concordia Theological Quarterly 71,2 (2007): 121-144.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.