At many Protestant churches on a Sunday morning, you see a platform with a band, a lengthy period of song with vocalists and instrumentalists in the center of the platform, electronic technology with screens and soundboards, informality, and no pastor visible until the sermon. How did this happen? Lester Ruth and Lim Swee Hong in their book A History of Contemporary Praise & Worship: Understanding the Ideas that Reshaped the Protestant Church (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2021) contend that there were two distinct rivers flowing in the twentieth century, one the Praise and Worship tradition originating from a Pentecostal background in the 1940s and the other the Contemporary Worship tradition originating in Methodist circles and with the Presbyterian Charles Finney of the early nineteenth century. In the 1990s there emerged a confluence between the two rivers that has significantly shaped the way Protestants worship. The authors note “the breadth of churches—Baptist, community churches, Bible churches, Lutheran, Presbyterian, independent and non-denominational, and Reformed, among others—caught up in the confluence that was Contemporary Praise & Worship” (303). The authors locate all of this in the Free Church tradition, which “has emphasized the freedom to shape congregational worship exclusively on the basis of Scripture. The freedom to follow Scripture has been paralleled by a freedom from being strictly tied to inherited forms of worship” (308).

In contrast, our Lutheran liturgical tradition comes from the Roman Catholic liturgical tradition. No liturgical tradition appears de novo. It is impossible for Christians simply to sit down with a blank slate and then based on the Bible alone create a style of worship from scratch. Such a quest is illusory. Each one of us lives within the flow of history, and every church has a historical heritage whether acknowledged or not. Our Lutheran liturgical tradition has a history. It does not come from Calvinism, Wesleyanism, or Pentecostalism but from the Western Catholic tradition. Martin Luther kept it and refocused it to celebrate the pure gospel according to the Scriptures.

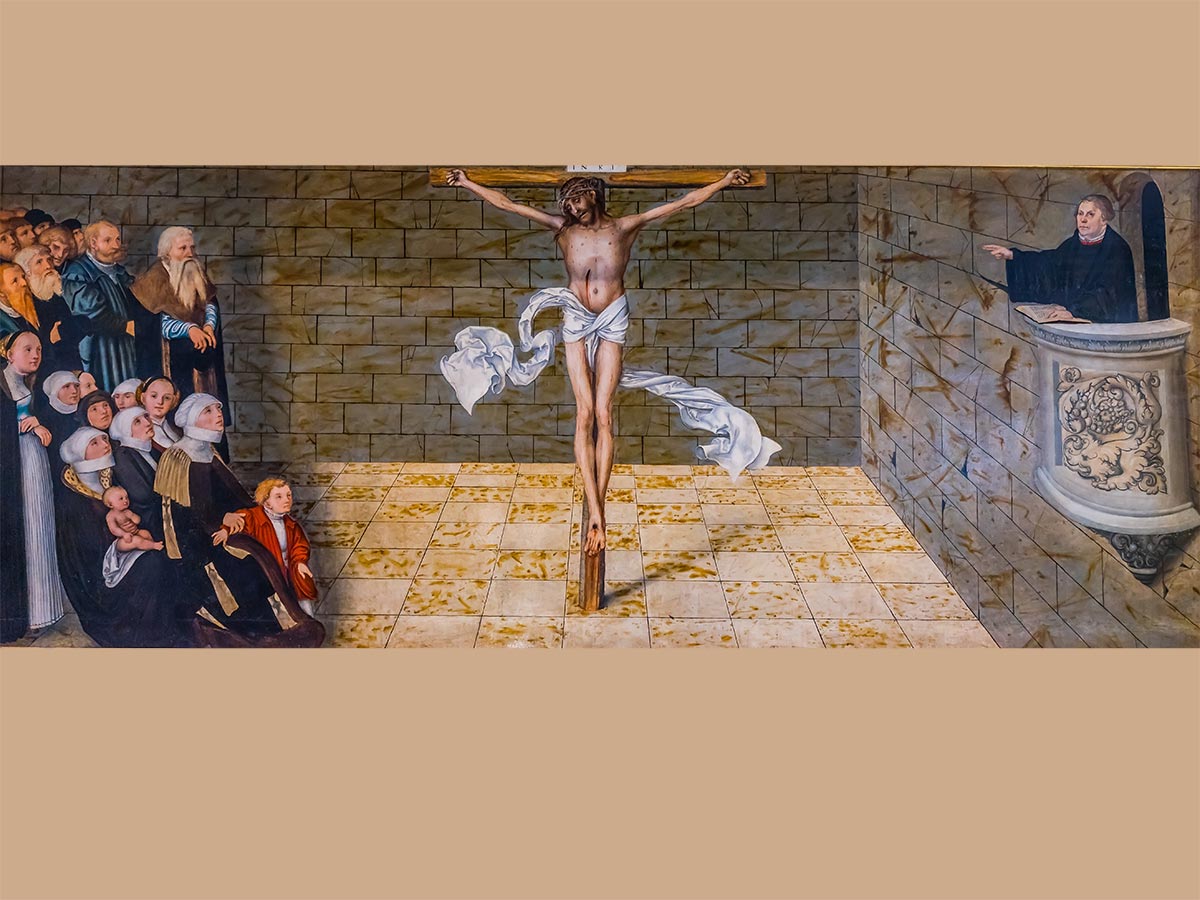

Therein lies a big challenge. Our liturgical tradition comes from Catholic roots, but the good people of our Lutheran churches are influenced more by American Protestantism than by Roman Catholicism, and especially by non-sacramental and non-liturgical “contemporary praise & worship” Protestantism. Our Catholic liturgical practices look odd to American Protestants. Our services are not simply a 45-minute motivational talk from a lectern plus a praise band. Our church buildings have stained-glass windows, give prominence to an altar, and some even have a cross with the corpus Christi on it. The pastor wears robes. We follow liturgical rubrics which have an old history.

So, what are we to do? The way forward is to play offense. In my opinion we should not attempt to blend our Lutheran liturgy with the tradition of “contemporary praise and worship.” The two worship traditions are more like apples and automobiles than simply apples and oranges. Nor is it persuasive simply to assert that we are Lutheran. Such an assertion is unintelligible in a country where 98 percent of the people are non-Lutheran. We are going to have to make the case for our Lutheran liturgy in the Catholic tradition in terms that are intelligible and persuasive to Americans who live in the twenty-first century and in a country heavily influenced by the Free Church tradition. The fastest growing church body in the United States today is Pentecostal. We have to “promote” our Lutheran liturgical tradition and that will require addressing basic questions.

The logic of Lutheran liturgical worship needs to be spelled out to Americans. That means, first, building up a biblical theology of liturgical worship. Our liturgical worship focuses on the central emphases of the Scriptures, the gospel, baptism, the Lord’s Supper, confessing the Trinitarian faith by the ancient creeds, and the Lord’s Prayer. This is all very biblical. And in making this argument the Old Testament can be of great help. Liturgical rituals can communicate godly theology. After all, God commanded ancient Israel to follow certain rituals. The entire Old Testament provides an abundance of material conveying liturgical theology. One thinks of the tabernacle texts in the Pentateuch, ancient Israel’s calendar of festivals and their sacrificial system, the Zion theology of Isaiah, the temple theology of Ezekiel and Chronicles, the Psalms focusing on corporate worship, and the rich sacramental theology related to tabernacle and temple. We will have to teach people about liturgy, and that means starting with the Scriptures.

Moreover, it will mean arguing for the value of liturgical worship that stands within the Western Catholic liturgical tradition. Our services are not informal but reverent, because Sunday morning worship is holy, not a common gathering for a motivational talk but being gathered together as God’s holy people who have been baptized into Christ and into his church. And his church has a history. We do not disown 100 to 1500 years of church history. There is only one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church, the visible marks of which are the Trinitarian faith, the pure gospel, baptism, the Lord’s Supper, and the Scriptures rightly taught. We affirm and embrace the God-pleasing heritage that has been handed down in the Western Catholic tradition. In the words of Martin Franzmann, “And all down the years the church, ‘by schisms rent asunder, by heresies distressed,’ has left monuments to the flaming presence of the Spirit in her creeds, her songs, her music, her architecture, her sculpture and painting, her stained glass that turns daylight into doxologies, and in all her simple, unrecorded arts of selfless love which we know happened then because they are happening now to us and among us who hear the same Word and are set aglow by the same Spirit” (Alive with the Spirit [Concordia Publishing House, 1973], 29–30). We affirm what is God-pleasing in church history and that includes what is God-pleasing in the history of the Western Catholic liturgy.

Why do we even follow a worship service with set rituals and rubrics? Because they convey a rich, orthodox, and biblical theology that leads sinners to repentance and faith, because they give all glory to God the Father through his Son Jesus and in the power of his Spirit, because they strengthen beleaguered Christians to remain faithful unto death and so receive the crown of life. The words, responses, and actions of a liturgical service do not express ex opere operato superstitions but edify toward faith. Our public worship practices focus on the gospel gifts from God and our response to the gospel gifts with congregational prayer and praise. Our liturgical actions convey meaning. For example, like the ancient Israelites our offerings are brought up to the altar to show that we are offering our tithes to God in response to his gospel gifts to us. There is a theological logic in our Lutheran liturgical heritage and that logic needs to be spelled out to average Americans.

In short, in the United States where the Free Church tradition is so prominent and influential, we Lutherans have to make the case in an intentional way for liturgical worship that is biblical and in line with the Western Catholic liturgical tradition.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.