In Nomine Iesu

When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son!” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother!” And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home. (John 19:26-27)

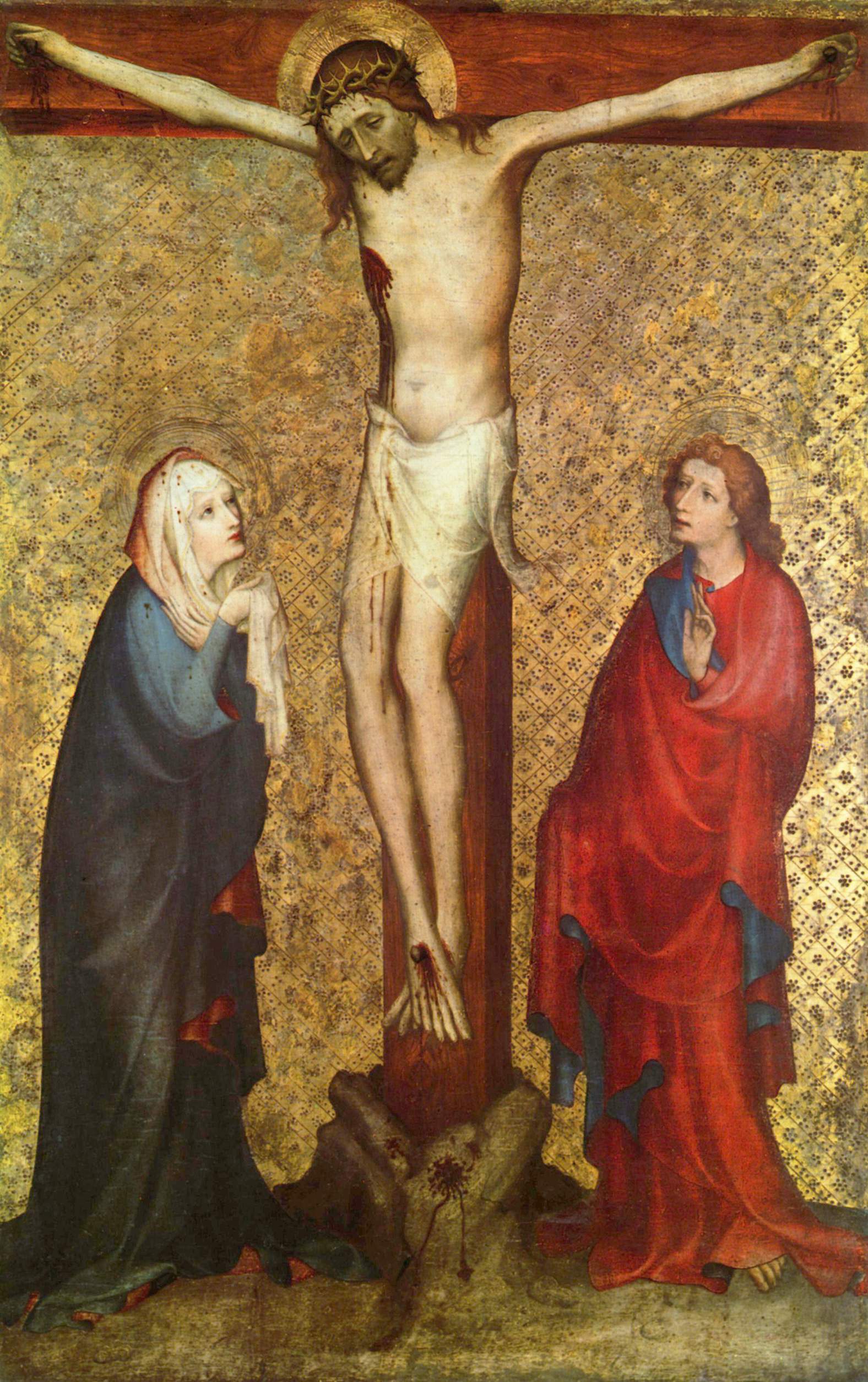

In this third word from the cross two figures capture our attention. There are more than two figures here of course: there are the soldiers, there are the women who followed Jesus and stand near, there is the disciple whom Jesus loved. But over the centuries, piety and preaching have focused especially on two: this moment between mother and son, Jesus and Mary.

Imagination has held on to this moment as the moment when a son has compassion on his mother’s broken heart. So it was with the famous 13th century hymn, Stabat mater dolorosa:

At the Cross her station keeping,stood the mournful Mother weeping,close to her Son to the last.Through her heart, His sorrow sharing,all His bitter anguish bearing,now at length the sword has passed.O how sad and sore distressedwas that Mother, highly blest,of the sole-begotten One.Christ above in torment hangs,she beneath beholds the pangsof her dying glorious Son.Is there one who would not weep,whelmed in miseries so deep,Christ's dear Mother to behold?Can the human heart refrainfrom partaking in her pain,in that Mother's pain untold?For the sins of His own nation,She saw Jesus wracked with torment,All with scourges rent:She beheld her tender Child,Saw Him hang in desolation,Till His spirit forth He sent.

We want John’s Gospel to give us a little insight into these final poignant moments—it’s the kind of thing we would expect from any good novel – it would certainly be there in the movies—the heart wrenching but oh so fitting “I love you’s” and “goodbyes.” But the Gospel gives us little to nothing in this regard. Still, we speculate that this must be a great moment of affection in which Jesus cares for his mother even in the midst of agony … similar to how we witness people who are dying make provisions to care for their family after they are gone. But again, the text of the Gospel gives us none of this. In some sense we get the opposite.

Think back to the beginning of the Gospel of John. In chapter 2 there is another exchange between mother and son. Jesus and his mother are invited to a wedding in Cana, and the host of the feast runs out of wine. Mary turns to Jesus and tells her son what has happened, knowing perhaps that he could help. But his response shocks us, a cold and distant: “Woman, what have you to do with me? My hour has not yet come.” But now, here in chapter 19, Jesus’ hour has come. Surely the compassion and affection of Jesus for his mother will be expressed in these final moments, his final hour. And yet I think our modern ears are disappointed as Jesus seems not to draw her closer but relinquishes his familial bond and gives his mother away to his disciple. Many attempts to salvage this moment have been made, arguing for how, culturally, at that time, these words of Jesus were in fact a great act of compassion for his mother. And while all of this may be true, it does, I believe, miss the point.

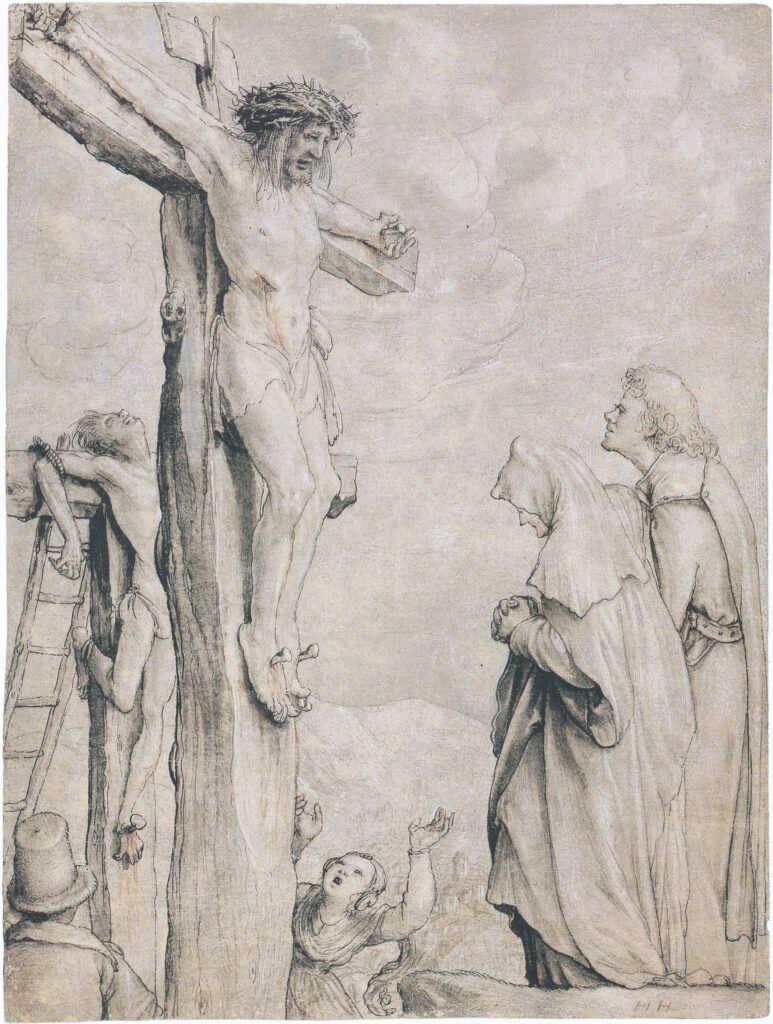

What we have here is not a singular act that is concerned with the relationship of mother and son. What we have in this moment with the savior of the world stretched out in agony is the beginnings of the church – Jesus fashioning a new family of people. The other Gospel writers give hints of this as well. For example, when Jesus was in the house with his disciples and his mother and brothers were outside, those around him appealed to the traditional family bonds—“your mother and brothers are here.” But Jesus looked at those gathered there and responded, “Here are my mother and my brothers! For whoever does the will of God, he is my brother and sister and mother.” And later, when Jesus announces that those who wish to be his disciples must leave everything behind—even one’s family—to follow him, he says: “Truly, I say to you, there is no one who has left house or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or lands, for my sake and for the gospel, who will not receive a hundredfold, houses and brothers and sisters and mothers and children.”

And so now at the cross, all of this begins. Those who are drawn to the cross, who believe and love Jesus, Jesus knits together, one to the other, as a new people who relate to one another in a new way as a family. Here at the cross, Jesus knits together his church.

So often we think of this day as a day when Jesus died for me. This is so very true and it must be grasped on this day, but it is only part of the story. Jesus’ death is not just about his love for me—it is about his love for the world. And what happens on that day is not just a transaction of guilt and sin and death between me and Jesus, but the beginning of a world called away from itself to be a new kind of community. And so we see here, at the very moment of Jesus’ death, we see birth—the birth of a new people, a new family whose bond to one another is deeper and wider than any family heretofore. It is the family of God—people from every tribe and race and language who are bound to one another through the faith and love of Christ who gave himself for us. Jesus looks at his mother and looks at the disciple whom he loved, and he sees the church. At the moment of his death, Jesus does indeed act out of great compassion and love for his family, but not his old family that will grieve over his death because he is gone, but a new family that will rejoice in his presence when he is alive again!

And isn’t this exactly how the church lives—not in fear of a death that will sever us from one another, but in confidence and hope that because of the Resurrection we are knitted together forever? Think of the description of the first years of the church in the Book of Acts. The chief priests and elders begin to threaten the disciples and prohibit them from preaching in the name of Jesus. And so the church comes together and prays, knowing that just as all the rulers of the people gathered together against Jesus the Christ and crucified him, so also they were setting themselves against his disciples. And what then did they do—batten down the hatches? Go into hiding? Prepare for the onslaught? No … they shared with one another. They offered up everything they had to each other so that no one was in need. In short, they lived together as one family having all things in common.

On this day, in the shadow of the cross, in the face of death, the church is born—Mary and this disciple begin this new family of God—a mother and brother of us all. And where there are even only two or three together in the name of Jesus … he is not absent or gone, but there in the midst of them. May we continue to live as brothers and sisters, mothers and sons of one another and of Jesus: one family, children of our Heavenly Father. Amen.

[A Treore sermon preached by Dr. Erik Herrmann on Good Friday, 2016]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.