Jon Diefenthaler contributes the following as a follow up to the “Book Blurbs” interview about his recent book, The Paradox of Church and World: Selected Writings of H. Richard Niebuhr. Dr. Diefenthaler is the retired president of the Southeastern District of The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), and a visiting professor in historical theology at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis.

Jon Diefenthaler contributes the following as a follow up to the “Book Blurbs” interview about his recent book, The Paradox of Church and World: Selected Writings of H. Richard Niebuhr. Dr. Diefenthaler is the retired president of the Southeastern District of The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), and a visiting professor in historical theology at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis.

*

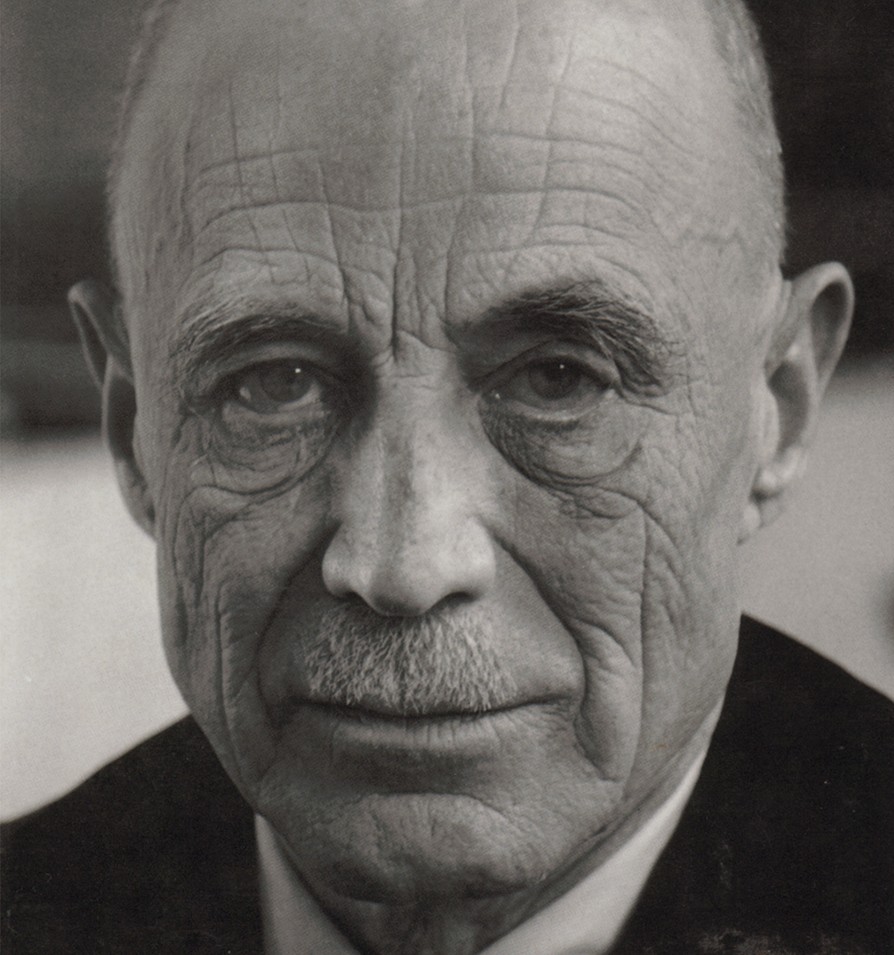

H. Richard Niebuhr (1894-1962) lived through and commented insightfully as a Christian theologian upon several periods of political crisis with remarkable similarities to the one we are experiencing in 2016.

Niebuhr witnessed one of them in Germany as a foreign observer in 1930. Hitler had not yet come to power. But the appeal of the Nazi version of fascism was unmistakable. Niebuhr attributed it to the reaction of many Germans to the Weimar Republic’s dysfunctional version of democracy, to the economic instability caused by an unfair treaty (Versailles) and their county’s loss of standing as a world power, to the evidence of moral decay at home, and to their scapegoating of a segment of the population.

“At this point,” or so Niebuhr wrote following the fall elections in which the National Socialists gained additional seats in the Reichstag, “there seems to be a dubious hiatus between the public expressions of the leaders and the actual program of the party. This promises the exclusion of Jews from public office, their disenfranchisement and sometimes seems to threaten deportation. The converse of this measureless hate of the Jews is the old chauvinism, the old proud self-exaltation of isolated nationalism and its associate—militarism.”[1]

Was there a time when America was truly “great”? Memory may take some of us back to the prosperous post-war years of the 1950s. What is conveniently forgotten, however, is the mortal fear of the spread of world Communism and the Cold War threat of nuclear annihilation that gripped our nation during this period. In fact, it precipitated a political crisis that was perhaps comparable to what we are experiencing in 2016.

What Niebuhr saw at the core of this “fear” on the part of many Americans was not so much the evils of a godless enemy, but the disruption and decline of their own beloved culture. As a result, they were tending to lose sight of the universal values on which their nation was founded and to confuse allegiance to the Christian faith with preserving the “American way of life.”

In the wake of this same crisis, Niebuhr called upon the church to declare its “independence” by asserting that “under God” was an all-important feature of America’s recently-revised Pledge of Allegiance. “Divine sovereignty” was the theological truth to which it pointed, and when Americans viewed their democracy from this standpoint, responsible citizenship on the part of everyone could only mean rejection of the assumption on the part of any “human authority—whether priest, preacher, magistrate, people, or popular majority—of the right to speak in the name of the absolute.” Furthermore, it clearly implied that “representative government” involved “selection by the people of [candidates] they trusted to be obedient to ultimate principles of right and to be concerned about the welfare, not of constituents only, but of the whole nation—indeed of mankind.”[2]

The political crisis of 2016 in America has its own unique features. However, the response of H. Richard Niebuhr to the isolationist-interventionist controversy of his day may be instructive for today’s church and its leaders.

The outbreak of wars in Asia and Europe in the late 1930s deeply divided the American people. Some favored an “America First” position and advocated strict neutrality, while others called for intervention in order to halt the advance of totalitarian aggression in the world beyond our country’s shores. Often, differences of opinion in church circles were just as sharp.

Was there anything helpful for pastors to say to their parishioners and to anyone else willing to listen? Equally abhorrent to Niebuhr was a church that either chose to retreat to the sideline of silence or to align itself with the ideology of a particular political party or faction. Instead, he argued that the “religious” issue at any critical moment was not about the content of each of the conflicting positions, but the context in which people had reached, or were justifying, their conclusions about them.

For Niebuhr, this context might be “egoistic” (what is the effect of this upon me?), or it might be “nationalistic” (what is in the best interest of America?). At the same time, the context might also be “universalistic” (what is the impact of this upon the entire human family?). This was in fact the context in which Niebuhr himself chose to operate because he believed there were no limitations that anyone could place upon the scope of God’s authority and activity.[3] He is Lord of all!

Nevertheless, Niebuhr encouraged the church’s leadership, in any public controversy, to consider employing his paradigm. Their task, as he saw it, was to probe critically the “religious” context in which all positions on a hot-button issue were being set forth, and then in light of their faith in God, to make up their own minds regarding the one they needed to support.

Endnotes

[1] See The Paradox of Church and World: Selected Writings of H. Richard Niebuhr, Fortress Press, 2015, p. 187-190.

[2] See The Paradox of Church and World: Selected Writings of H. Richard Niebuhr, Fortress Press, 2015, p. 324-335.

[3] See The Paradox of Church and World: Selected Writings of H. Richard Niebuhr, Fortress Press, 2015, p. 407-412.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.