It is now 500 years since Luther’s translation of the New Testament first appeared. It is no exaggeration or hyperbole to praise Luther’s German Bible as not only one of the most important works in the German language but also as one of the great literary achievements of Western history. It is well known that Luther’s Bible was the single most influential work in shaping and standardizing the modern German language. But it also set a standard for subsequent efforts to reproduce the Scriptures in the vernacular, in the every-day language of the people. William Tyndale studied Luther’s translation carefully, taking over Luther’s approach to the text and also translating, often verbatim, Luther’s own introductions and prefaces to each book of the Bible. Of course the great tradition of the early modern and modern English Bible is deeply indebted to the genius and brave work of Tyndale and Coverdale and the 17th century divines in the court of King James. Nevertheless, Luthers Bibel was both an inspiration and a wellspring for rise of the modern vernacular Bible.

But Luther did not initially set out to do this. The seeds of this work were sown long before in his own deep, spiritual struggles. A son of the times, a son of the church, a son of the austere order of St. Augustine, Luther’s personal angst arose from the prevailing piety of the day which set forth an inner conflict, a tension between two poles. On the one hand, the truly religious was to take up the posture of the penitent, a humble confessor of sins, an introspection of one’s own weaknesses, and imperfections. On the other hand, one should also make every effort to achieve holiness which was nothing short of a perfect love for God. Taking this with the utmost seriousness, Luther was trapped within himself, examining his own soul, each insincere act of love, each pious work that still retained a hint of pride, each incomplete confession, all the while finding not love, but frustration, fear, even anger toward God. Luther’s mentor and superior, Johann von Staupitz tried to help him but Luther’s prison was his own conscience. And so Staupitz gave Luther the greatest gift—he forced him, *ordered* him to study the Scriptures—to become a doctor of theology and an expositor of the Bible. This shift, to direct Luther’s assiduous and keen mind away from himself, away from the state of his inner condition and instead outside himself, to an external text—this shift is perhaps the most important of Luther’s life. The result was a fastidious wrestling with Holy Scripture, with Paul, with the sentence “the just shall live by faith”:

“I beat importunately upon Paul at that place, most ardently desiring to know what St. Paul wanted. … At last, by the mercy of God, meditating day and night, I gave heed to the context of the words, namely, “In it the righteousness of God is revealed, as it is written, ‘He who through faith is righteous shall live.’” There I began to understand that the righteousness of God is that by which the righteous lives by a gift of God, namely by faith. And this is the meaning: the righteousness of God is revealed by the gospel, namely, the passive righteousness with which merciful God justifies us by faith, as it is written, “He who through faith is righteous shall live.” Here I felt that I was altogether born again and had entered paradise itself through open gates.”

Holiness and righteousness was not to be found within oneself but rather without—in the holiness and righteousness of Jesus offered upon the cross and bestowed to us as a gift by the very promises of God in his word. Not the ebb and flow of piety inside us but the promise of God outside of us, constant, firm and sure, for God is faithful to his word.

Thus it became clear to Luther that he would not reform the church. It was the Word of God that would do it. “I simply taught, preached, wrote God’s Word; otherwise I did nothing. … I did nothing; the Word did everything.” And so, for Luther the goal of everything he did was to let that Word sound forth clear, so that every man, woman and child might hear the voice of the living God, that all might be taught of God. It was for this reason that Luther became a translator of the Bible.

Luther’s development as a translator began early on, already in his earliest lectures. He was installed as a doctor in Biblia—a doctor of the sacred Scriptures in October of 1512, but he didn’t give his first lectures until the Fall of 1513—on the Psalms. Some scholars have conjectured that there must be a missing lecture of Luther from that time. But when one begins to study those first lectures on the Psalter, one sees that Luther did an enormous amount of preparatory work. He prepared a new version of the Latin Psalms to be printed out for the students. But this was unlike any existing Psalter. Luther had made changes to the text, based Hebrew and other Latin readings besides the Vulgate. Such insights were made available to him through the Renaissance humanist scholars Faber Stapulensis and his Quincuplex Psalterium, as well as Johannes Reuchlin’s Hebrew grammar, De rudimentis hebraicis.

Luther’s next set of lectures were on Romans, and there he consulted the Greek New Testament that had just been published by Erasmus of Rotterdam. At this point, Luther became convinced that the university needed to reform its theology curriculum and put Scripture back into its center. Moreover, he began to ask the Elector of Saxony for new faculty, those that could teach Greek and Hebrew so that the Bible could be read in the original languages as well as the Latin Vulgate. And in 1518, the university of Wittenberg received its first Greek professor, a young rising star of humanism, Philip Melanchthon.

Luther as Translator

But this kind of work was not merely for the classroom. Luther was increasingly sensitive to the need to reform pastoral care. The 95 Theses were actually aimed precisely at this: the abuse of indulgences as bad pastoral care. In that same year he also published a translation of the Seven Penitential Psalms into German, with brief commentary. It was his first published work written for lay people, in the vernacular.

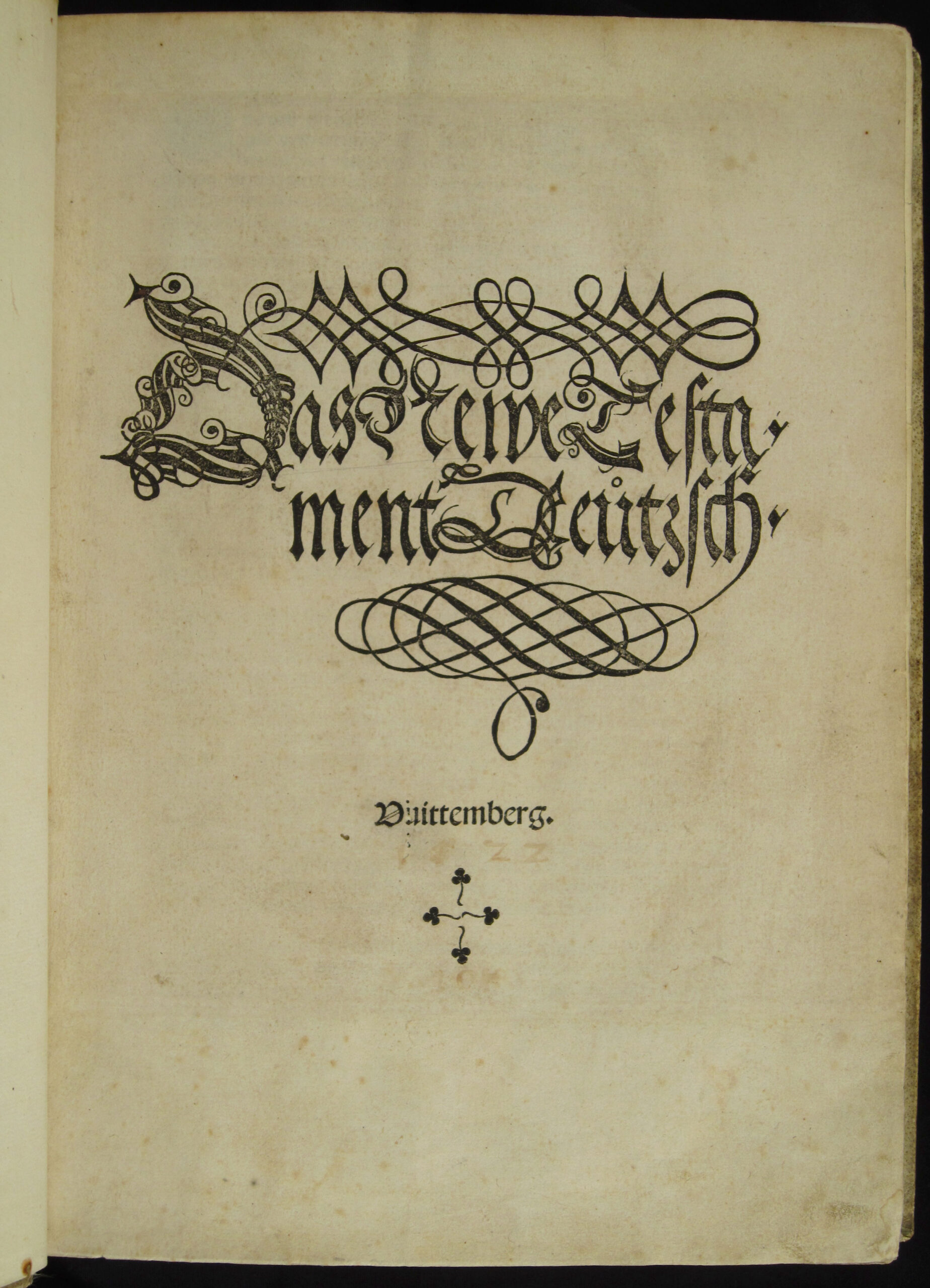

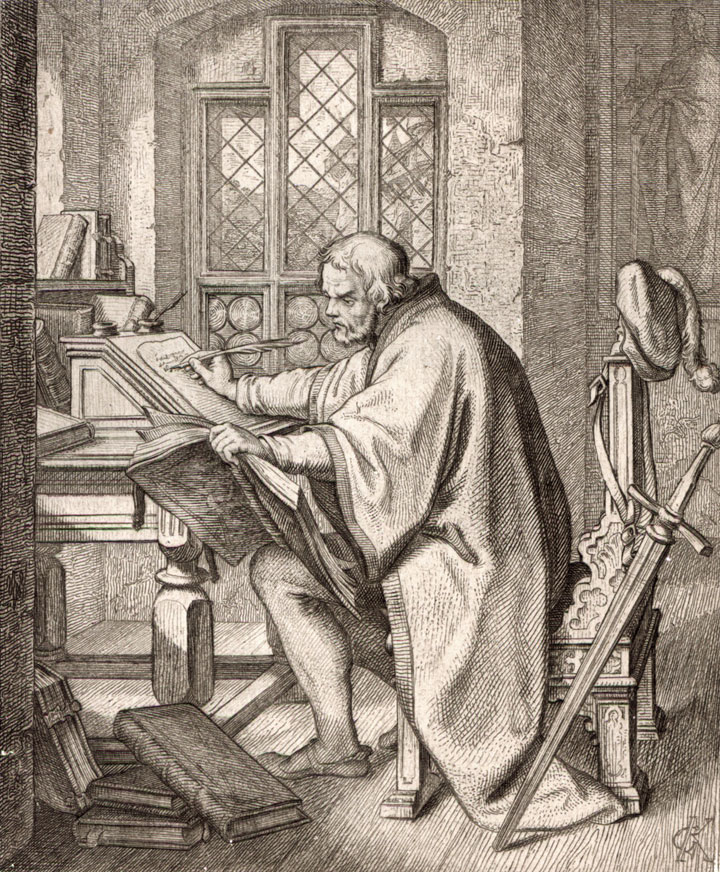

In the following years, the case against Luther interrupted this work, but by 1520 he wrote to his friend, Johannes Lang, that he planned to translate the whole Bible into German. But that too was interrupted by his summons to Worms in 1521. Whisked away to the Wartburg castle for his protection, Luther used the time to return to the project that lay so dear to his heart. In only eleven weeks time, Luther managed to produce a fresh translation of the New Testament, not only from the old Latin Vulgate, but using the Greek as well. In September of 1522 his New Testament was published along with an introduction on how to read the Gospels, prefaces and brief marginal notes. It sold 5,000 copies in 2 months, 50 printings in four years, and over 200,000 over the course of the next 12 years.

Upon returning to Wittenberg, Luther continued his work of translation, producing German versions of Old Testament books from Genesis to Song of Songs in 1522-24. He consulted his colleagues, especially those who excelled in Greek and Hebrew, Melanchthon, Justus Jonas, Caspar Cruciger, Johannes Bugenhagen, and Matthäus Aurogallus— his *Collegium Biblicum* and little “Sanhedrin.” By 1534 the work was complete and published with 117 original woodcuts from Lucas Cranach’s workshop for illustration. Even so, Luther continued to revise the translation until his death. In Luther’s lifetime ten complete editions of the Bible appeared and about eighty editions of parts of the Scriptures were published in Wittenberg alone, while around 260 editions appeared in other parts of Germany and Europe.

Luther on Translating

The genius and power of Luther’s translation lay in his remarkable ability to bring the sense of the text into authentic German idiom. The idea of translating according to what we might call “dynamic equivalent” rather than word-for-word, did not begin with Luther. Jerome defended this approach for Latin, for example. But Luther’s gift for capturing the essence of a passage and making it understandable to the common German speaker was nothing short of remarkable. He described the task as a difficult one, recognizing how easy it is to lose the beauty and power of the original:

“We are now sweating over a German translation of the Prophets,” he wrote. “O God, what a hard and difficult task it is to force these writers, quite against their wills, to speak German. They have no desire to give up their native Hebrew in order to imitate our barbaric German. It is as though one were to force a nightingale to imitate a cuckoo, to give up his own glorious melody for a monotonous song he must certainly hate. The translation of Job gives us immense trouble on account of its exalted language, which seems to suffer even more, under our attempts to translate it, than Job did under the consolation of his friends, and seems to prefer to lie among the ashes.”

Luther’s broad education was invaluable but even then he would spend weeks listening carefully in the market place to the spoken language of the mother and servant girl in order refine his word choice.

But Luther’s translation did not escape the criticism of his opponents. In his open letter on translating, Luther wryly noted that translating is like building a house by the side of the road—everyone is a critique thinking they can do it better. But Luther retorted:

“I have not compelled anyone to read it. Rather I have left that open, only doing the work as a service to those who could not do it better. No one is forbidden to do it better! If someone does not wish to read it, he can let it lie, for I do not ask anyone to read it or praise anyone who does so. … If I have made some mistakes in it, I will still not allow the papists to be my judges. For their ears are still too long and their hee-haws too weak for them to criticize my translating. I know quite well how much skill, hard work, sense and brains are needed for a good translation. They know it even less than the miller’s donkey, for they have never tried it.”

Still, Luther went on to defend his work, setting forth his methodology and his understanding on the nature of language. To illustrate he discussed his choice when translating Gabriel’s greeting of Mary:

When the angel greets Mary, he says: “Gegruesset seistu, Maria vol gnaden, der Herr mit dir” [Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with you]. Up till now this has simply been translated according to the literal Latin. But tell me, is that good German? Since when does a German speak like that, “du bist vol gnaden” [you are full of grace]? One would have to think about a keg “full of” beer or a purse “full of” money. Therefore I translated it: “du holdselige” [you O favored one]. This way a German can at least think his way through to what the angel meant by his greeting. Now the papists are throwing a fit about me corrupting the Angelic Salutation, yet I still have not used the most satisfactory German translation. Suppose I had used the best German and translated the salutation: “Gott grusse dich, du liebe Maria” [God greet you, dear Mary], for that is all the angel meant to say, and what he would have said if he had greeted her in German. Suppose I had done that! I believe that they would have hanged themselves out of their fanatical devotion to the Virgin Mary, because I had so destroyed the Salutation.”

“On the other hand I have not just gone ahead and disregarded altogether the exact wording in the original. Rather, with my helpers I have been very careful to see that where everything depends upon a single passage, I have kept to the original quite literally and have not departed lightly from it. For instance, in John 6 Christ says: “Him has God the Father versiegelt [sealed].” It would have been better German to say “Him has God the Father gezeichent [signified]” or even “He it is whom God the Father meinet [means].” But I preferred to do violence to the German language rather than to depart from the word.”

Most famous of course was his insertion of the word “alone” in Romans 3:28, “For we hold that one is justified by faith alone apart from works of the law.” Here Luther defends his translation on the basis of the German language, theology, and most importantly, the consciences of spiritual lives of people.

“Therefore the matter itself, at its very core, requires us to say: “Faith alone justifies.” The nature of the German language also teaches us to say it that way. In addition, I have the precedent of the holy fathers. The dangers confronting the people also compel it, for they cannot continue to hang onto works and wander away from faith, losing Christ, especially at this time when they have been so accustomed to works they have to be pulled away from them by force. It is for these reasons that it is not only right but also necessary to say it as plainly and forcefully as possible: “Faith alone saves without works!” I am only sorry I did not also add the words alle and aller, and say, “without any works of any laws.” That would have stated it with the most perfect clarity. Therefore, it will remain in the New Testament, and though all the papal donkeys go stark raving mad they shall not take it away. Let this be enough for now.”

These remarks illustrate for us how Luther does not see the task of translation purely from the standpoint of accuracy or scholarly insight. For Luther translation is also an act of faith and an act of pastoral care.

For more on the significance of Luther’s translation of the Bible you can listen to my discussion with Dr. Rich Rudowske of Lutheran Bible Translators at https://lbt.org/luthers-translation/.

On October 13 [2022], Concordia Seminary and Lutheran Bible Translators will host a public lecture focusing on Luther’s translation of the New Testament and its significance, featuring Dr. Jeffrey Kloha, chief curatorial office of the Museum of the Bible in Washington D.C. and Dr. Vilson Schulz, visiting professor of Exegetical Theology at the Seminary and former translation consultant for United Bible Societies. For more information see https://www.csl.edu/event/500th-anniversary-lecture-martin-luthers-new-testament-translation/

Erik Herrmann

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.