In honor of the observance of the Reformation, let’s delve a little bit into history. After all, the Reformation is an event embedded in history, and the reformers saw themselves as inheritors and preservers of the teaching of the historical church. They were not inventing new teaching, they were returning to what both Scripture and the faithful teachers throughout all generations had taught. A down-and-dirty way to summarize their theology, encapsulated in thousands of stained glass windows, are the three great solae of the Reformation: sola fide, sola gratia, sola scriptura. These are not just bland assertions, self sufficient and unrelated. As if you just need to say “Scripture alone” and fill in the blanks for whatever you want to do (find you purpose driven life, prove the age of the earth, etc.). No, “sola” is in the ablative case, here used to indicate means. So the phrases are translated — unlike the stained glass window pictured here — by faith alone, by grace alone, by Scripture alone. The obvious question then becomes, why the “by”? What, exactly are faith, grace, and Scripture a means toward? The answer is cleverly portrayed in our stained glass windows: at the center is a cross. Faith, grace, and Scripture are the means — repeat that — the means by which we receive Christ. And so the great solus (nominative singular masculine) is solus Christus — Christ alone. And he is received by faith (not works), by grace (not our merit), by Scripture (not councils or tradition).

In honor of the observance of the Reformation, let’s delve a little bit into history. After all, the Reformation is an event embedded in history, and the reformers saw themselves as inheritors and preservers of the teaching of the historical church. They were not inventing new teaching, they were returning to what both Scripture and the faithful teachers throughout all generations had taught. A down-and-dirty way to summarize their theology, encapsulated in thousands of stained glass windows, are the three great solae of the Reformation: sola fide, sola gratia, sola scriptura. These are not just bland assertions, self sufficient and unrelated. As if you just need to say “Scripture alone” and fill in the blanks for whatever you want to do (find you purpose driven life, prove the age of the earth, etc.). No, “sola” is in the ablative case, here used to indicate means. So the phrases are translated — unlike the stained glass window pictured here — by faith alone, by grace alone, by Scripture alone. The obvious question then becomes, why the “by”? What, exactly are faith, grace, and Scripture a means toward? The answer is cleverly portrayed in our stained glass windows: at the center is a cross. Faith, grace, and Scripture are the means — repeat that — the means by which we receive Christ. And so the great solus (nominative singular masculine) is solus Christus — Christ alone. And he is received by faith (not works), by grace (not our merit), by Scripture (not councils or tradition).

One problem the reformers had was that they were bucking their contemporaries. To emphasize Christ alone and the means by which he is received was not what the church of their day was doing, nor did many, it seems, before them. Were they making it up? Were they claiming some kind of new revelation from the Holy Spirit? Did they find Bible passages that no one had noticed before? Far from it. The reformers made clear in their great confessions of faith (especially in the Augustana, the Apology, and the Formula of Concord) that they are teaching what the church catholic (universal) has always taught, and they went to great lengths to cite the great fathers of the church in support of this “new” teaching.

One of the fathers they cite is Ambrosiaster. Well, that’s not his name. In the Lutheran Confessions he is cited as “Ambrose” (AC 6; Ap 4,235 [though in error]; and Tr 27). Even from antiquity no one knew who penned this great commentary on the Pauline Letters (Augustine, for example, called him “Hilary”). In 1527 Erasmus figured out that it was not written by Ambrose (it was written during the papacy of Damasus, 366-384), but apparently this cutting-edge scholarship didn’t make its way to Wittenberg by 1530. In any case, what Ambrosiaster offers, and what the confessors cite in the Augsburg Confession, is an example of the use of the phrase sola fide:

It is established by God that whoever believes in Christ shall be saved without works, by faith alone, receiving the forgiveness of sins as a gift.(translation from Kolb/Wengert edition, p. 41)

You might expect, being a good Lutheran, that this is taken from Ambrosiaster’s commentary on Romans 3, or Galatians 2, or Ephesians 2, or some other great declaration of justification by faith. But in fact it occurs in the comments on 1 Cor 1:4 (“I always give thanks to my God for you, because of the grace of God which is given to you in Christ Jesus.” Here Ambrosiaster notes, “that whoever believes in Christ is saved sine opera. sola fide he receives freely (gratis) the forgiveness of sins.” This may well have been the earliest use of the phrase sola fide, especially connected with sine opera, that was known to the reformers. For some reason they don’t draw upon Ambrosiaster’s comments on, say, Rom 3:24, where very similar wording can be found (“they are justified freely (gratis), because neither doing anything nor repaying something in return they are justified by faith alone (iustificati sunt sola fide) by gift of God.”). Perhaps the clear “without works” is lacking here; perhaps Ambrosiaster reads the passage within its first century context and rightly notes repeatedly that Paul is dealing with the distinction between Jew and Gentile that is causing problems in the church in Rome. Who’d have thought — the “New Perspective on Paul” in the fourth century!

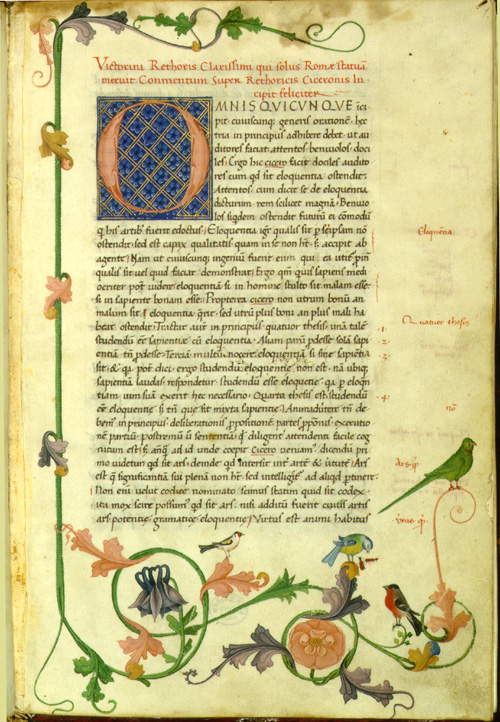

What the reformers could not have known was that another old guy, Marius Victorinus used similar language. You may never have heard of him, but he has one of the more fascinating stories of conversion in the early church, taking place as it did in the context of the reign of Julian the Apostate. Marius was the rhetor laureate of the empire, and was apparently the only living person to have his statue erected in the Forum in Rome. But he converted to Christianity from his neo-Platonism, a conversion story which had a profound impact on Augustine. Julian, however, would have none of this. Marius was banished from Rome and retired to apply his considerable skill and intellect to Christian thinking. One of his great monuments, of which only portions are preserved, is his commentary on Paul’s Letters. Marius reads Paul as Paul was written to be read (heard): as Greco-Roman rhetoric. So Marius understands the context, the flow of argumentation, the addressees, the grammar, textual variants, all those things that exegetes fuss over. His commentary style (though sadly not the wording of the commentary itself) became quite influential in western Christianity, and influenced Ambrosiaster, Pelagius, Cassiodorus, Sedulius Scottus, and others. An excellent edition of his commentary on Galatians was published in 2005 by S. A. Cooper, with a discussion of Marius’ life, context, and thinking. It is highly recommended, though the going price means that you may have to request it at your local library via ILL.

What the reformers could not have known was that another old guy, Marius Victorinus used similar language. You may never have heard of him, but he has one of the more fascinating stories of conversion in the early church, taking place as it did in the context of the reign of Julian the Apostate. Marius was the rhetor laureate of the empire, and was apparently the only living person to have his statue erected in the Forum in Rome. But he converted to Christianity from his neo-Platonism, a conversion story which had a profound impact on Augustine. Julian, however, would have none of this. Marius was banished from Rome and retired to apply his considerable skill and intellect to Christian thinking. One of his great monuments, of which only portions are preserved, is his commentary on Paul’s Letters. Marius reads Paul as Paul was written to be read (heard): as Greco-Roman rhetoric. So Marius understands the context, the flow of argumentation, the addressees, the grammar, textual variants, all those things that exegetes fuss over. His commentary style (though sadly not the wording of the commentary itself) became quite influential in western Christianity, and influenced Ambrosiaster, Pelagius, Cassiodorus, Sedulius Scottus, and others. An excellent edition of his commentary on Galatians was published in 2005 by S. A. Cooper, with a discussion of Marius’ life, context, and thinking. It is highly recommended, though the going price means that you may have to request it at your local library via ILL.

Cooper’s volume includes a detailed discussion of the use of the phrase sola fide in Marius. One selection Cooper highlights is Marius’ comment on Gal 2:16:

We, says Paul, we have believed in Christ, and we do believe in order that we might be justified based on faith, not works of the Law, seeing that no flesh—that is, the human being who is in flesh—is justified based on works of the Law. So knowing this, if we have believed that jusitification comes about through faith, we are surely going astray if we now return to Judaism, from which we passed over to be justified based no on works but faith, and faith in Christ. For faith along grants justification and sanctification (Ipsa enim fides sola iustificationem dat et sanctificationem). Thus any flesh whatsoever—Jews or those from the Gentiles—is justified on the basis of faith, not works or observance of the Jewish Law.

According to Cooper, this is “perhaps the earliest Latin formulation of Paul’s theology in those terms.” (Cooper, pp. 152-153). While preceding Ambrosiaster by perhaps only a decade or two, it is significant that yet another voice that taught sola fide can be cited from early Christianity. The authors of the Lutheran Confessions had more support than they perhaps thought.

Notably, both Marius Victorinus and Ambrosiaster — and for that matter the authors of the Lutheran Confessions — got their theology and phrasing from a close reading of the New Testament letters of the Apostle Paul. They didn’t dream this up out of their heads. They didn’t deduce sola fide from other doctrines, or come to this conclusion at the end of a systematics discussion. They all got the theology and the wording directly from the New Testament. Funny how that happened. They actually practiced sola scriptura.

But wait, there’s more. Permit one more example from an early commentary, this on on Gal 2:14 (where Paul is addressing Cephas):

And not Judaically. Not on the basis of works of Law, but by faith alone (sed sola fide) do you yourself [Cephas] recognize that we [Jews] gain life in Christ, just as also do the Gentiles.

I’ll give you a million dollars (not really) if you correctly identify the source of this use of sola fide. No peeking. . . . Okay, now scroll down . . .

The author of this statement is none other than the enemy of sola fide, Pelagius. I counted twelve references in the Lutheran Confession to Pelagius and the Pelagians, some quite extensive. I didn’t check all of them, but I’d doubt that any of them have anything positive to say about Pelagius and his theology. And rightly so. But even Pelagius got it right when he stuck to the text. Lift up your eyes from the text and what do you get?

There is a lesson in all this, I think. First, be an exegete (but you knew that I was going to say that). But more importantly, read the text. Mark the text. Inwardly digest the text. And then speak it back to God, yourself, and his people. Then you end up with things like sola fide, because they are in the text. One of the dangers of Christians of all ages, all the way from Pelagius (and well earlier) and down to our own day, is that we leave the text behind — sometimes with good intentions, sometimes not. But when we leave the text behind we end up teaching and preaching ourselves. Permit a couple examples, all, I think, well-intentioned. And, my apologies to any non Lutherans reading this, all of these are our Lutheran issues (perhaps ironically, among Lutherans). How do we talk about such issues as worship? The work of the pastor? What the Christian life looks like beyond Sunday morning? The sad fact of divisions and speaking about one another that does not “build up the body” but tear it down? Have we lifted our eyes from the text, pondered stuff in our small, little brains, and come up with something that must assuredly be true?

Lord, keep us steadfast in Thy Word / Curb those who by deceit or sword / Would wrest the Kingdom from Thy Son / And bring to nought all He has done. Curb us, also, from ourselves.

BTW, Lectionary at Lunch covers the epistle reading for this week: Romans 3:19-28 (if you read this after Oct 31 click here). (I apologize in advance for the length, but there is so much to get at in this text. I only hope that Marius Victorinus would approve).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.