by David R. Maxwell

Editor’s note: When Concordia Theology was redesigned in spring 2010, a significant amount of content was archived. Some of that content is simply too good to leave behind. So, in the coming months we will be digging deep into the “CT Vault” and bringing out the theological gems you’ve been missing. David Maxwell’s excellent overview of Lutheran Christology (with pictures!) seemed like the perfect place to start. If you have recommendations for old Concordia Theology pieces you want to see resurrected, email us at [email protected]. Welcome to the Concordia Theology Vault!

INTRODUCTION

At the heart of Lutheran Christology lie the three genera of communication of attributes. Genus is the Latin word for “kind.” “Attributes” are the divine or human characteristics that Christ possesses. Therefore, when we speak of three genera of communication of attributes we are talking about three kinds of sharing that take place between Christ’s natures and person. You can think of it as three different kinds of statements that the Scriptures make about Christ.

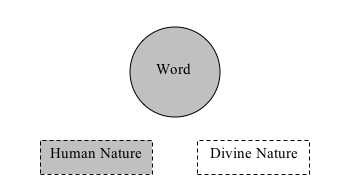

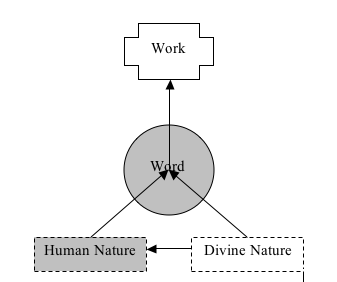

Before we examine the three genera, we need to say a few words about how Lutheran Christology describes Christ. We may illustrate Lutheran Christology with the following diagram:

This diagram indicates that the Word is the only acting subject in Christ. There is no assumed man who acts independently as there is in Nestorian Christology. Because of the incarnation, the Word is a man. This is indicated by the gray shading. In summary, Lutheran Christology is the same as that of Cyril of Alexandria.

The boxes with dotted lines indicate Christ’s natures. The lines are dotted to indicate that the natures do not have any independent existence from the incarnate Word (represented by the circle). However, in order to speak of the two natures, we need to make a mental distinction between them. That is why there are two boxes.

THE GENUS IDIOMATICUM

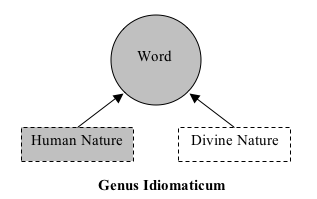

Idioma is the Latin word (derived from Greek) for “attribute.” The genus idiomaticum is that class of communication in which attributes are communicated from both natures to Christ’s person. It may be illustrated as follows:

From his divine nature, the Word has such divine attributes as omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence, and so forth. From his human nature, the Word has such human attributes as spatial location, the ability to suffer, the ability to grow, etc. The point of the genus idiomaticum is that the Word has both sets of attributes.

A scriptural example of the genus idiomaticum is Paul’s statement, “They would not have crucified the Lord of Glory” (1 Cor. 2:8). Here Paul is attributing crucifixion not to a human Jesus considered apart from the Word, but to the Lord of Glory himself. In so doing, Paul is attributing the human attribute of being able to suffer to the Word. Lutherans describe this kind of predication with the term genus idiomaticum.

Another scriptural example is Paul’s statement that “the Son was descended from David according to the flesh” (Rom. 1:3). How could the Son of God be descended from David? Being descended from David is a human attribute which the Word has because of the incarnation. This does not mean that the Son took his origin from David. That is the point of Paul’s qualifier “according to the flesh.” The Word does not receive the human attribute of being descended from David from his divine nature, but from his human nature.

Within the genus idiomaticum we use the phrase “according to” to designate which nature gives the particular attribute in question to the person. For example, we might say that Christ dies “according to the human nature.” This does not mean that only the human nature dies. That would be a Nestorian position in which the human nature functions as an independent acting subject. Instead, “according to the human nature” specifies that the Word receives the human attribute of being able to die from his human nature, not from the divine nature. It is still the Word, however, who undergoes crucifixion and death.

THE GENUS MAIESTATICUM

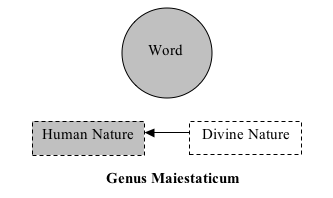

The genus maiestaticum is the “majestic genus” because it deals with the communication of divine majesty from Christ’s divine nature to his human nature. We may diagram this genus as follows:

The primary importance of this genus has to do with the Lord’s Supper because we want to confess with the Scriptures that Christ’s body and blood give us life and forgive our sins. Christ’s body and blood are part of his human nature, and the Scriptures clearly attribute divine power to his body and blood. For example, Jesus says, “If anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever. This bread is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world” (John 6:51). John says, “The blood of Jesus his Son purifies us from all sin” (1 John 1:7). Giving life and purifying from sin are divine attributes that Christ’s human nature has because of the incarnation.

We use the phrase “according to” in the genus maiestaticum as well, but here it means something different than it does in the genus idiomaticum. In the first genus, it refers to the nature which gives the attribute. In this genus, it refers to the nature which receives it. For example, when we say that Christ received divine power “according to his human nature” (genus maiestaticum) we mean that his human nature received the power. However, when we say that Christ died “according to his human nature” (genus idiomaticum), we mean that the human nature provided the attribute of mortality.

One might ask the question whether the human nature communicates human attributes to the divine nature, or more technically: Is there reciprocity in the genus maiestaticum? The answer is no. The communication goes only one way: from the divine nature to the human nature. If the communication went the other way, the divine nature would become susceptible to human weakness. Although we say that “God” (i.e., the Word) has human attributes because of the incarnation, we do not say that the “divine nature” has human attributes.

THE GENUS APOTELESMATICUM

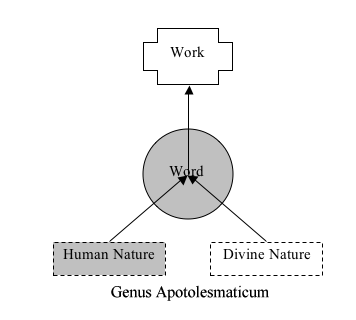

The genus apotelesmaticum is similar to the genus idiomaticum except that it focuses on the relation of Christ’s natures to his work rather than to this person. An apotelesma is a work. We may diagram this genus as follows:

According to the genus apotelesmaticum, everything that Christ does, he does utilizing both natures. He never “turns off” his divine nature. We can use the same passages we used for the genum maiestaticum to illustrate the genus apotelesmaticum. When Jesus says that he will give his flesh “for the life of the world” (John 6:51), we can identify both natures in this one action. He gives his flesh (human nature), and this flesh gives life (divine nature). Likewise, when John tells us that “the blood of Jesus his Son purifies us from all sin” (1 John 1:7), we can identify both natures at work together in this act of purification. The purification is accomplished by Jesus’ blood (human nature) which has the power to forgive sins (divine nature).

A denial of the genus apotelesmaticum would mean that one of Christ’s natures becomes inert and irrelevant to his actions. For example, some people claim that when Christ did miracles, he did not use his divine nature at all, but merely did the miracles by the power of the Holy Spirit. It is certainly true that the Holy Spirit is involved in Christ’s miracles, but it would be a denial of the hypostatic union to say that Christ functioned merely as a man and not as the God-man.

CONCLUSION

We may synthesize all three genera into one diagram as follows:

The fundamental point of Lutheran Christology is to emphasize the unity of Christ. The genus idiomaticum does this by specifying that the Word is the one acting subject in Christ whether he is drawing more obviously on his divine or human attributes at any given moment. The genus maiestaticum does this by stressing the close connection between the divine and human natures—so close in fact that the human nature actually receives divine attributes. The genus apotelesmaticum does it by specifying that both natures always work together when Christ performs his work.

This emphasis on Christ’s unity is critically important for soteriology. If it was not the Lord of Glory who was crucified (genus idiomaticum), we are still in our sins. If the body of Christ cannot give life and the blood of Jesus cannot purify from sin (genus maiestaticum) then the Lord’s Supper is of no benefit to us. All of Christ’s actions are divine and human (genus apotelesmaticum) because God’s plan of salvation is to send his Son to become man for our salvation.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.