In an essay on Johann Gerhard’s understanding of the “confessio catholica,” first published in 1997, Bengt Hägglund concluded by writing that despite being bound strictly to his own time and expressing himself in a scholarly fashion long ago laid aside, “Gerhard sought in the century-old controversies for a buttress for what he called the confessio catholica, the evangelical truth, which is a summary of Scripture and a firm rule for the faith.” With an effective use of contemporary historical scholarship (and perhaps bound to our context as well – time will tell), Professor Hägglund served Christ’s church for nearly three quarters of a century as a sharp-eyed, critical reader of the sources of the tradition of the church and a gifted author, analyzing the course of its proclamation of God’s Word.

In an essay on Johann Gerhard’s understanding of the “confessio catholica,” first published in 1997, Bengt Hägglund concluded by writing that despite being bound strictly to his own time and expressing himself in a scholarly fashion long ago laid aside, “Gerhard sought in the century-old controversies for a buttress for what he called the confessio catholica, the evangelical truth, which is a summary of Scripture and a firm rule for the faith.” With an effective use of contemporary historical scholarship (and perhaps bound to our context as well – time will tell), Professor Hägglund served Christ’s church for nearly three quarters of a century as a sharp-eyed, critical reader of the sources of the tradition of the church and a gifted author, analyzing the course of its proclamation of God’s Word.

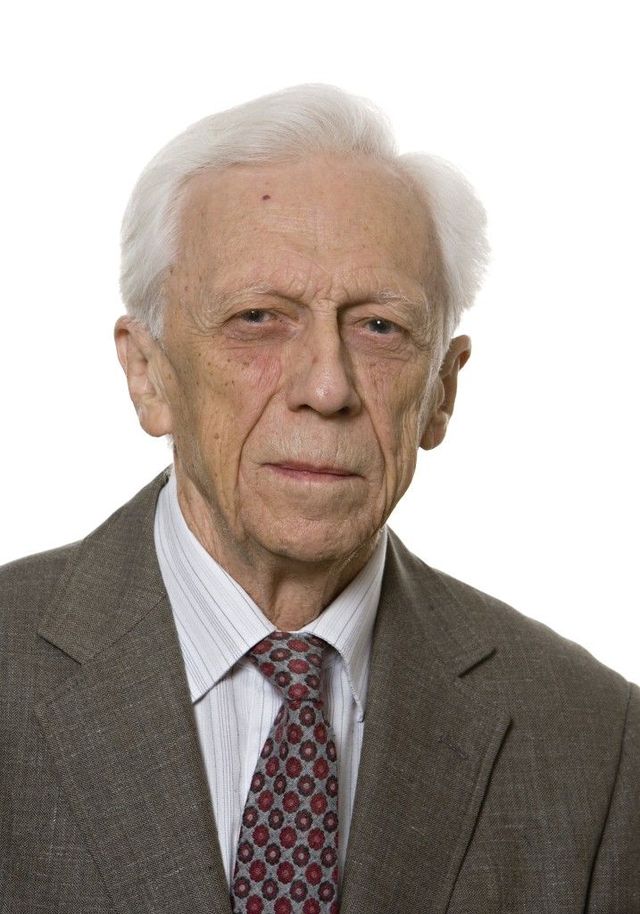

On March 8, 2015, the Lord of the church called Bengt Hägglund to himself, shortly after the long-time professor of church history at the University of Lund had completed a new Swedish translation of Luther’s Small Catechism, the heart of his faith and piety. Born November 22, 1920, Hägglund concluded his education at the University of Lund in 1951 with a dissertation that pioneered sober scholarly assessment of the much-ignored and much-maligned period often labeled “Lutheran Orthodoxy.” Johannes Wallmann and Karl-Heinz Ratschow in Germany and Robert Preus in the United States followed in his footsteps, opening the way for the slowly growing examination of seventeenth-century Lutheran thought, but Hägglund remains the premier student of Nordic theology in the period as well as, to the last, a significant contributor to the study of its early modern German Lutheran cousin. His initial work in his dissertation, Holy Scripture and Its Interpretation in the Theology of Johann Gerhard, an Investigation of the Old-Lutheran Understanding of Scripture, still stands as an important source for information and analysis of the subject.

Hägglund explored the roots of the Reformation alongside its impact as well. His study of Theology and Philosophy in Luther and in the Ockhamist Tradition. Luther’s Position on the Theory of Double Truth pioneered in-depth study of the medieval sources of Luther’s thinking when it appeared in 1955. Four years later his De homine. Conceptions of Human Nature in the Old-Lutheran Tradition was published in Swedish, again promoting the discussion of biblical anthropology that has grown immensely in recent years. His career has produced a number of other significant monographs; he edited classics of Swedish theology (e.g. his edition of the Loci theologici of the seventeenth-century Swedish theologian, Johannes Rudbeckius [2001]) and contributed a wide range of insights in essays.

My first encounter with Professor Hägglund’s work came as I was leaving seminary. His History of Theology appeared in English from Concordia Publishing House. This work has been translated into German, Portuguese, Latvian, and Russian, serving generations of students across the globe. We then met at an International Luther Congress, and through my association with Församlingsfakulteten in Göteborg, we had several other occasions to converse. His gentle manner and his critical mind combine with a skill at conveying ideas in their historical context with the result that he has instructed thousands of those interested in the history of the church and particularly the Lutheran tradition. It was a great honor for me when his student Torbjörn Johansson of Församlingsfakulteten asked me, along with Johann Anselm Steiger, to edit a Festschrift for Professor Hägglund at the occasion of his ninetieth birthday, Hermeneutica Sacra. Studien zur Auslegung der Heiligen Schrift im 16.- und 17. Jahrhundert / Studies of the Interpretation of Holy Scripture in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2010). At the birthday celebration in Göteborg, he had brought as a gift for participants his edition of a seventeenth-century Swedish edition of the German theologian Matthias Hafenreffer’s Compendium doctrinae coelestis, which had appeared in print that very week. I asked, “Professor Hägglund, we have but one question: what is your next project?” He smiled his quiet smile and said, “You have to have a project.” The last of these was the new translation of the catechism.

His baptismal Lord imprinted on this life of dedication and service the image for which he prayed in his favorite hymn, composed by the Danish pastor and hymnwriter, Thomas Hansen Kingo:

On my heart imprint your image, Blessed Jesus, King of grace,

That life’s riches, cares, and pleasures never may Your work erase.

Let the clear inscription be: Jesus, crucified for me,

Is my life, my hope’s foundation, and my glory and salvation!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.