This is part two of a series of posts from Dr. David Maxwell. The first post was “What Should You Do With Anger and Desire?”

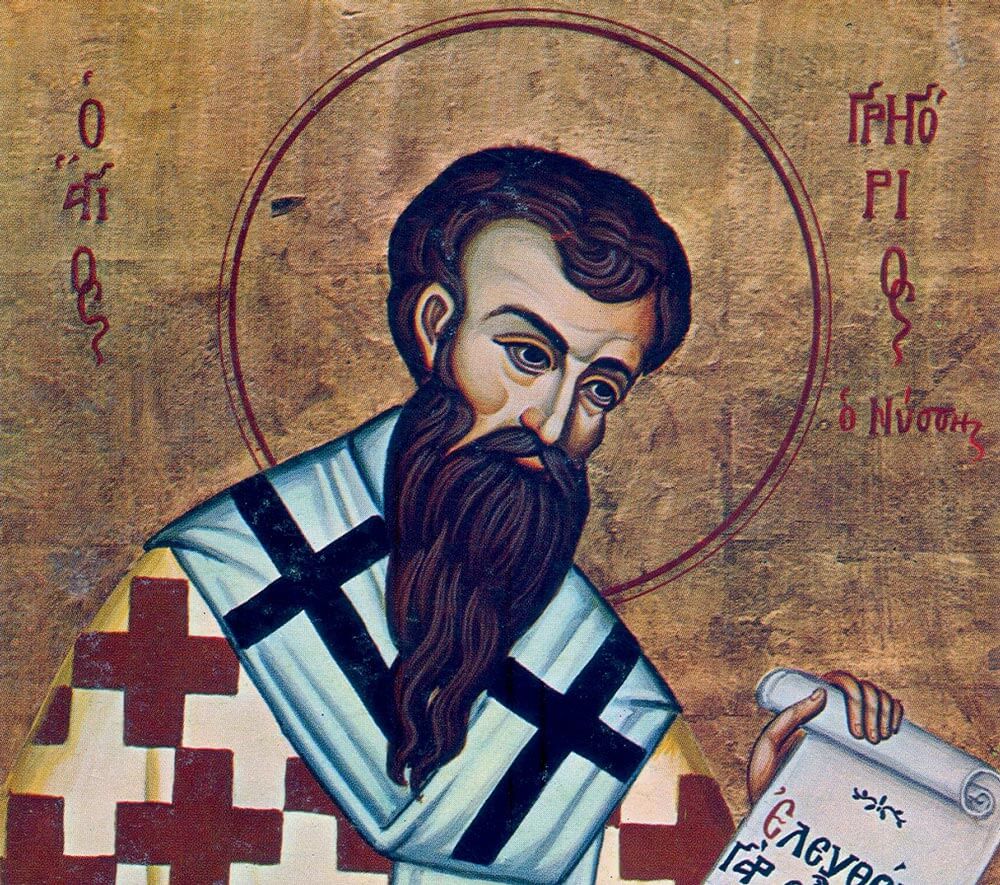

Gregory of Nyssa’s On the Soul and the Resurrection is a treatise that demonstrates what a Platonic spirituality of the passions looks like when Christians adopt it. The dialogue is a conversation between Gregory and his sister Macrina, who is attempting to comfort Gregory in the face of the death of their brother Basil, and Macrina’s own impending death. She does this by instructing him about the nature of the soul and the resurrection.

They both agree that they want to derive their understanding of the soul from the Scriptures, not from Greek philosophy. At one point, Macrina even says, “We shall abandon the Platonic chariot and the pair of horses yoked to it” (On the Soul and the Resurrection, p. 50). Those two horses are anger and desire. Ultimately, however, Gregory finds anger and desire to be a helpful way of categorizing the scriptural teaching about the passions. He says, “The soul obviously has a great impulse of desire and another great impulse of anger” (p. 49). And he goes on to say that all other passions are derived from a combination of these two.

If you look through the sins mentioned in the New Testament, it looks like Gregory might be right about this. For example, we have the following list in Ephesians 4:31: “Let all bitterness and wrath (θυμὸς) and anger and clamor and slander be put away from you, along with all malice.” You might classify these as “anger” sins. It even includes θυμὸς, the name for one of the Platonic horses! Then a few verses later, we get this list in Ephesians 5:3: “But sexual immorality and all impurity or covetousness must not even be named among you, as is proper among the saints.” You might classify these as “desire” sins. Now I don’t think this anger/desire classification accounts for all sins in the New Testament. Unbelief, for example, doesn’t seem to fit. But it does account for a lot of them.

So where do these passions come from? According to Gregory, Adam and Eve were not created with passions, but they entered through the fall. So, you might think that Gregory wants the Christian to eliminate the passions as much as possible. However, that is not the view he takes. He maintains that one can deploy the passions either for good or for evil, just as the same steel can be forged either into a sword or a plowshare.

The Scripture text that he uses as the pattern for the Christian life when it comes to passions is the parable of the wheat and the tares (Mt 13:24–30). Jesus says that we should not root out the tares because in the process we might uproot the wheat as well. Similarly, in Gregory’s view, if you try to eliminate the passions, you will also destroy the possibility of using those passions for good. “If love is taken away,” says Macrina, “in what manner will we be joined with the divine? If anger is quenched, what weapon will we have against our adversary” (p. 59)?

Gregory, then, proposes a version of Christian spirituality that recognizes that it would be dangerous to try to eliminate anger and desire and the other passions, even though they are sinful and are a result of the fall. Instead, he thinks that the Christian should try to direct the passions in a godly and constructive direction. As we shall see in the next post, not all church fathers share this view.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory of Nyssa, On the Soul and the Resurrection, trans. Catherine P. Roth (Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1993). The material on the passions is in chapter 3.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.